“Zwarte Piet is a centuries-old tradition for children, but for some reason adults get very upset about it.” This is how my Dutch language teacher introduces our lesson on the history of “Sinterklaas” and Dutch Christmas traditions.

Now, my teacher’s off-the-cuff Dutch history lessons have previously been painfully hit-and-miss, from casual ignorance of the country’s atrocities in Java and South Sulawesi, to a particularly generous minimisation of the Dutch East India Company’s war-mongering, mass incarcerating, and colony-forming tendencies. My experience is that this omission is typical of Dutch narratives around slavery and colonisation – the Rijksmuseum’s account of the Dutch East India Company is effervescent with pride, and fails to mention slavery at all.

Therefore, my anticipation of a lesson introducing the Netherlands’ shameful blackface “Santa’s helper” character Zwarte Piet (Black Pete), was heavily dominated by anxiety.

To backtrack a little: Zwarte Piet first became part of Dutch festive mythology in 1850. The character was depicted in a picture book by a whimsical guy called Jan Schenkman. In this imagining, Zwarte Piet is Sinterklaas’ black… “servant”. Whilst slavery on Dutch soil was technically illegal by 1850, the reality was slightly more nebulous (as it was across Europe), and people from Africa would often be brought into the Netherlands via the slave trade, and “given” as presents to wealthy families.

In present-day Netherlands, parades, TV shows, and swathes of seasonal marketing feature the character of Zwarte Piet, exclusively depicted by a white person “blacked-up”; donning a curly Afro wig and gold earrings, and with painted thick red lips. Depictions of the character on packets of festive sweets and cheerful chocolates generally veer towards a ‘“sambo” or “gollywog”-esque caricature with cartoonish red lips and jet black skin.

A few minutes into the lesson the teacher asks us: “Wat denken we over Zwarte Piet?”/ “What do we think about Zwarte Piet?” A fellow student responds that Zwarte Piet is a jester who gives candy to children, and – he supposes – some people think that it has a “racist element”. I swiftly follow his comments with my own perspective – “Ik denk dat Zwarte Piet is racisme”, and for the rest of the lesson, the teacher no longer solicits our thoughts on the matter.

The lesson oscillates somewhere between absurd and deeply traumatising, as we are given worksheet after worksheet plastered with blackface images, with no context, or caveat that of course these images are awful, and racist, and for me, at least, incredibly painful to look at.

At one point the teacher projects a video on a screen showing the “intocht” – the arrival of Zwarte Piet in Maastricht, with hordes of blacked-up Dutch people joyously dancing around and grinning ghoulishly into the camera. The teacher points to the screen – her finger literally touching a blacked-up face – and, with ill-founded relief, I think that she is finally going to comment on how horrific this all is. Continuing to point excitedly, the teacher exclaims in Dutch: “Look at the crowds! Crowds and crowds of children lining the river to see the arrival of Sinterklaas!”

I wonder if I’m the only one who can sense the elephant in the room – this cumbersome creature whose hefty feet are crushing my chest and making me want to vomit all over my exercise book.

I am distressed that my teacher thinks that Zwarte Piet – an unequivocal manifestation of violent colonisation that is clearly alive and well in the Netherlands – is merely light-hearted fodder for a language lesson. I am alarmed – and not by any means for the first time in my life – that as I look around the classroom my fellow students (all of whom are white), are pleasantly occupied with noting down new terms and phrases, and seemingly wholly unaffected by the horrendous images we have been presented with.

At the end of the lesson the teacher projects a video from 2015 of a man protesting against Zwarte Piet (simply wearing a T-shirt that says “Zwarte Piet is racisme”), and being brutalised by police. I avert my gaze from the screen and doodle in my exercise book – a lifelong strategy I’ve employed to distract myself from situations that wrench my gut.

But this video clip acts as the finale: after 1 hour and 25 minutes of blackface being presented as simply festive whimsy, the teacher tells us that due to campaigns against blackface in the Netherlands, times are a-changin’ and that modern-day Piets are starting to forego total blackface for “soot marks” on their cheeks. The logic goes that Zwarte Piet is now “black” because he fell down the chimney, and not because colonialisation necessarily makes a dehumanising mockery of black bodies.

The class clucks with neoliberal relief: “Oh, that’s good; yes that’s better!”.

The teacher hastens to add that despite pressure from the UN, many Dutch people are holding fast to their traditions, and that over two million people “Liked” a Pro-Piet Facebook page in 48 hours – a record for the Netherlands.

As we pack away our books, one of my fellow students begins to regale us with stories of Christmas parties at the Dutch embassy – where he would worry that passersby on the street would see party guests in blackface and get the “wrong idea”!

“But what would be the right idea?” I mutter.

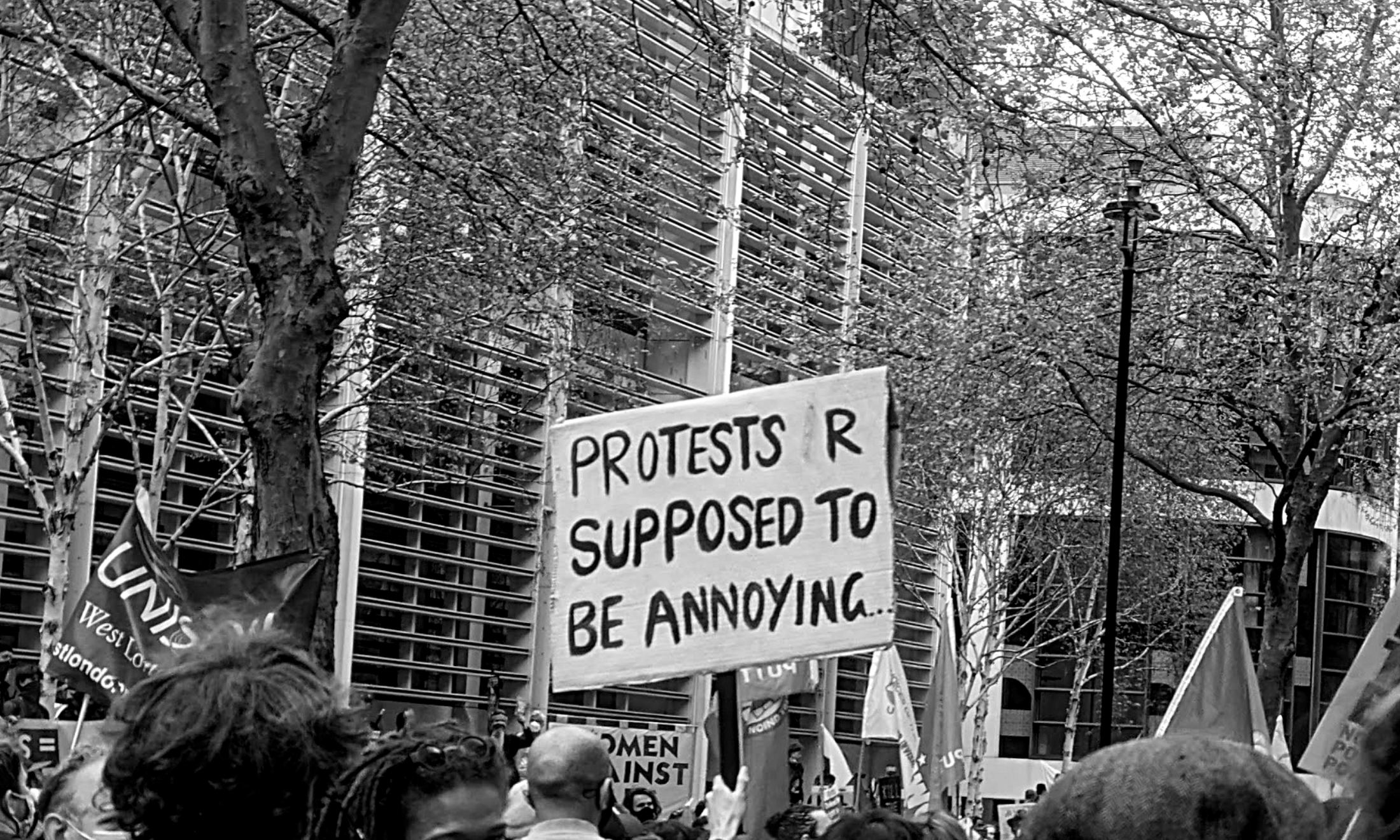

While the Netherlands refuses to acknowledge its colonial past and present, groups like Zwarte Piet is Racisme, and Stop Blackface shoulder the burden of dragging the debate out of 19th century picture books and into the present day, in addition to battling the slew of racism and microaggressions that truly mark the arrival of Sinterklaas for people of colour.

Obviously there is nothing salvageable about blackface, however it is dressed up. And suggestions that Zwarte Piet can be adapted, amended, and retained to satisfy both right-wing and neoliberal palates simply attempts to sweep under the carpet a history that the Netherlands desperately needs to confront.

Image by Nicole Chui (@thatsewnicole)