‘You don’t see many of them round here’: being black in the white, rural West Country

Louisa Adjoa Parker

05 Sep 2016

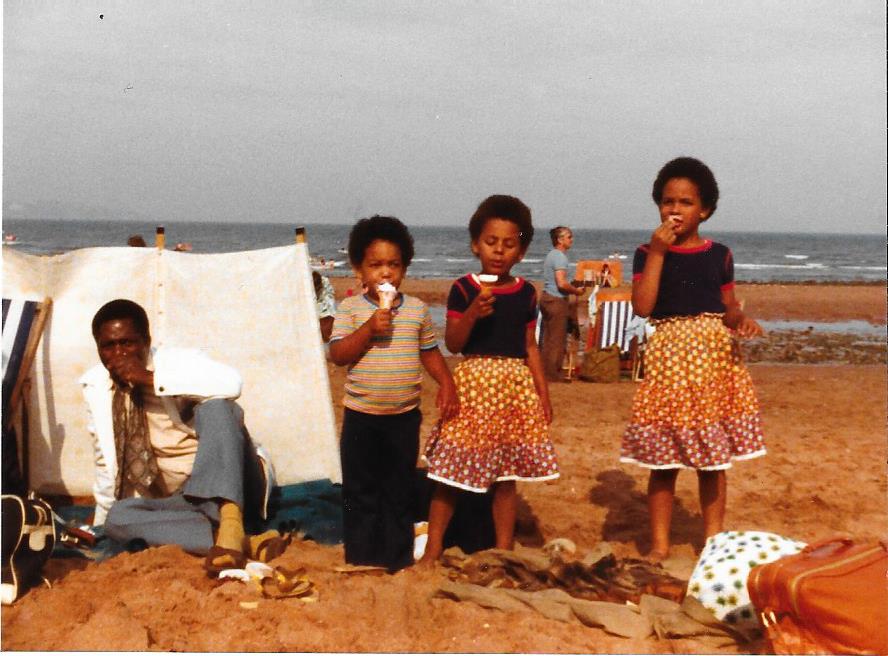

My parents met when my dad came to the UK from Ghana in the 1960s to train as a nurse. He married my mum, and I was born in Doncaster in 1972. I don’t think he had a clue before he came how racist Britain was then, and both my parents were naïve in their own ways. Their turbulent marriage was unsuccessful, not, as my grandparents had feared, as a result of two different cultures colliding, but because of two very different personalities colliding (and my dad’s fists colliding with parts of my mum’s body).

Many people of mixed heritage talk of the difficulties of belonging to two cultures. I didn’t have that problem – my dad rarely offered anything in the way of Ghanaian culture. We didn’t eat Ghanaian food, listen to Ghanaian music, or have contact with any of our Ghanaian relatives. In fact, Ghana has always seemed to me, a far-off, mystical, hot and dusty land, peopled by unknown relatives. My dad wanted to become English; he looked up to them, liked their ways. I’ve not yet visited, although I hope to soon, and am grateful to my brother for flying out there and finding our long-lost family.

In 1985 I moved to Paignton, Devon, with my white, English mum, brother and sister. My parents had recently split up, and Mum wanted to be near my English grandparents. The move was like going back in time, and the early ‘70s was not a place I wanted to go back to. Huntingdon, with its flat fenlands and burning stubble, had been slightly multicultural – we had a Japanese friend, and another friend whose mum was mixed, like us. Devon was white, whiter than white. I don’t think I even set eyes on another brown face (apart from those of my siblings) for a couple of years. We were the only ones for miles around.

Although I hadn’t wanted to move, south Devon, with its red earth, green hills and beaches was at least familiar to me, as we’d been visiting the grandparents for years. I quickly set about trying to befriend the natives. The girl next door informed me that her dad hadn’t wanted blacks living next door. She was nice, but the boys racially abused us. My brother later told me they sometimes beat him up. Later though, I even went out with two of them for a few days (although they didn’t want anyone to know), and these boys were happy to try and stick parts of themselves into me. They often came in our house, but they still called us the n-word, and much more besides.

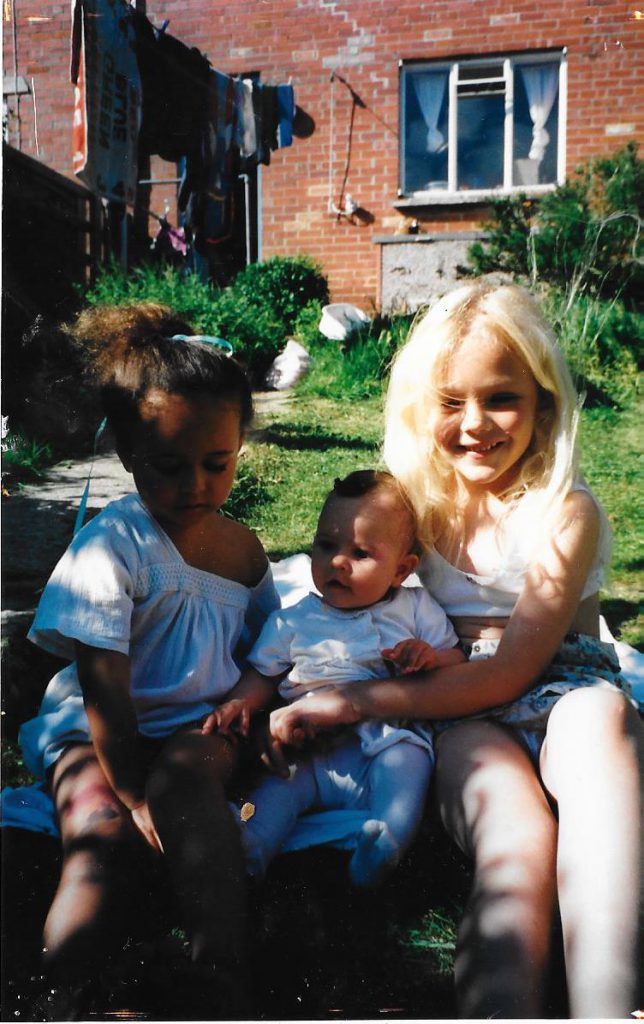

I was grateful that I went to school in Totnes, which was full of middle-class hippies and therefore had less (or at least more subtle) racism. I didn’t experience name-calling there, and made lots of friends, but as an adolescent I struggled with my mixed-ness. I hated myself. I believed I was hideous and fat, and would stare in the mirror for hours, wondering why I was so ugly. I hated my wide face and frizzy hair, and didn’t have a clue what to do with it. I had a hair-curler – the 80s equivalent of GHDs – and my friends would tease me as I took it everywhere. It was only years later, when my sister had her hair relaxed, that I discovered there was a whole world of haircare for black women. I tried hard to blend in with my white friends, and longed – as I had always done – to be white, skinny and blonde-haired.

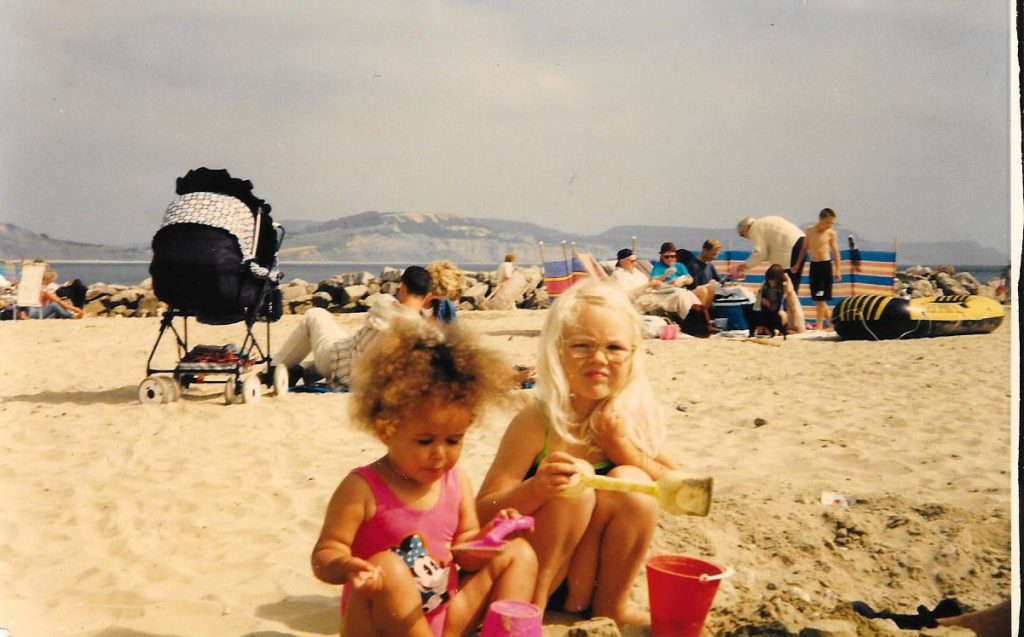

When I was 19 I moved with my (white, blonde, is she adopted?) baby to Lyme Regis. Here, racism was present but subtle – people didn’t generally abuse me, but I was made aware of my “otherness”. The people of seaside towns often dislike outsiders generally, but if you are black, there is another layer of dislike, which I believe stems from ignorance and fear. Author Caryll Philips wrote of “head-snapping” when he walked into a country pub, and Lyme was a town of head-snappers. When first I lived there, the only BAME people were myself, my sister, our Ethiopian friend and the families who ran the Indian and Chinese restaurants. Once I tried to buy cigarettes, and the newsagent refused to serve me, saying, “There’s three of you. I don’t know which one you are.”

My children and I got told racist jokes, and racism went unchallenged. There was plenty of “I’m not a racist, but…” and friends would talk about their dislike for black or Asian people, saying, “Not you, Louisa, you’re OK.” I had to tell someone off for referring to their stereo as a “wog box”. Over the years I’ve heard and experienced so many examples of racism, with the perpetrator not having a clue they are being racist. Once I attended an NHS equality and diversity training session in Dorset, and the trainer said – I kid you not – “I’m not a racist, I was engaged to a Jamaican, for goodness sake!” White, conscious friends have told me how another white person at the school gates, assuming all white people are on the same racist page, would tell them they’d left London to get away from all the blacks/Asians/ethnic minorities. A friend in Uplyme went to the post office after I’d just been in, and was told, “You don’t see many of them round here.”

Although numbers of BAME people in the south west are low, the population has grown and will no doubt increase further. For example, the BAME population in Dorset increased from 3.2 per cent in 2001, to 4.4 per cent in 2011 (ONS). People of mixed heritage are the fastest-growing ethnic group in England and Wales, numbering nearly one million, and that seems to be the picture here, too. I’ve witnessed this growth, and often see brown faces in Dorset and Devon now. Although experiences for BAME people vary, reports such as Racism and the Dorset Idyll showed that the majority experienced racism, ranging from inappropriate terminology, touching skin and hair without permission, to verbal abuse and physical attacks.

Last week I was saddened to hear of a Turkish kebab shop owner in Weymouth having a swastika painted on his shop. He’d moved from previous premises to get away from the constant racism. My friend’s son was badly beaten on Bournemouth beach. A bus driver in Dorchester, where I live now, was the victim of racially-motivated assault, and he set up the One World festival to celebrate diversity.

I could go on. I could talk about being referred to as “coloured”, or how it feels when white people assume anyone in the vicinity with brown skin is a relative. “Is that your sister?” “No, she’s Ethiopian, I’m half Ghanaian. Look at us.” I could talk about the fact that the n-word was scratched into a wall at my daughter’s school for years, and no teacher removed it. I could write a book, and perhaps I will. Living as a person of mixed heritage in a white part of the UK, and being the only brown face when I walk into a room, has been a strange, challenging experience.

But, I have grown through it, and discovered that writing – books and exhibitions exploring BAME people’s experiences, as well as poetry and fiction – has helped me understand that this area in fact has a multicultural past, and that I, like other BAME people, have every right to be here. We belong, we inhabit this space, and if our faces don’t quite fit against the landscape, with its rolling hills and light and space, then perhaps it’s time to rethink, and move into a future where they do.