The Women’s March on London, like its American counterpart, was not without controversy. Calls for a more intersectional approach on social media were met with grave hostility and accusations that women of colour were making the march “too political” and “divisive” – a synonym to the U.S. planning process and debate. But the updated guiding principles that emerged unexpected two days before the march were impressive: intersectional, inclusive and recognising existing power structures. I was surprised and confused.

What was going on? I spoke to three women of colour involved in the Women’s March on London, to share their stories.

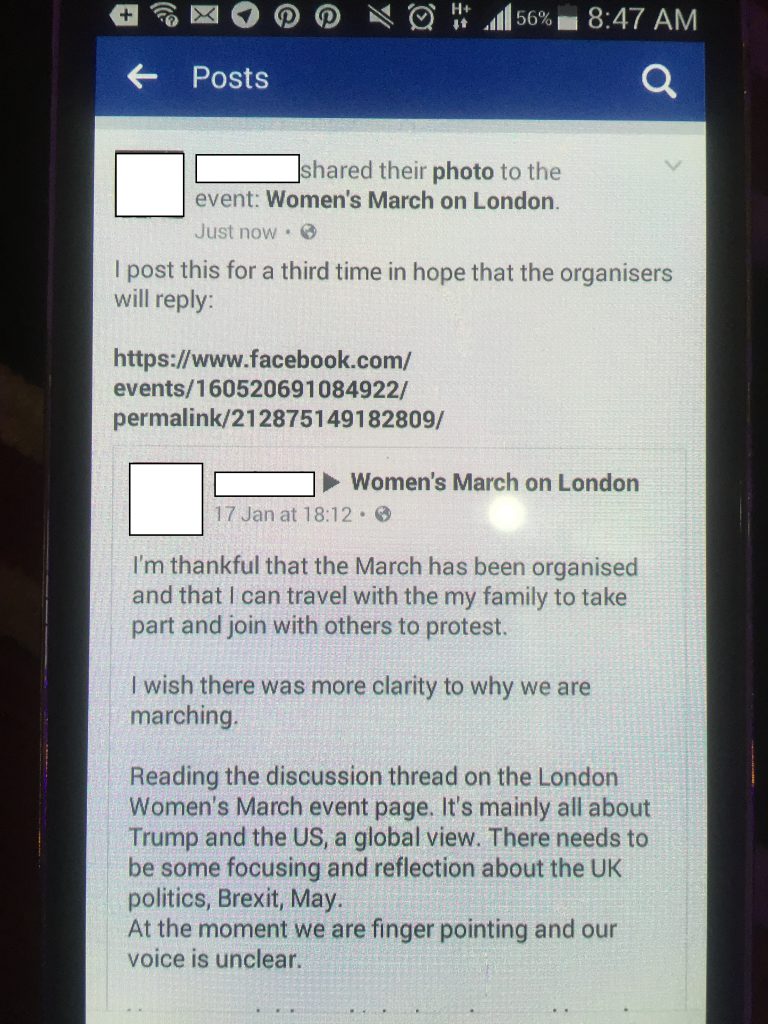

Social media was the setting where uncomfortable and tense debates unfolded. When they called for an intersectional approach that tackled issues affecting them head on some women of colour felt unsafe, under attack and branded “petty” or “divisive”. Worse still, original posts that had gotten heated had been deleted out of embarrassment. This led some collectives to remove their support for the march and release statements explaining their position. Rumours of a pro-life block and the removal of support for sex workers were rife. Angela Camacho, a long-time social and political activist based in London, told me she felt exhausted and attacked after engaging in debate on the Facebook event.

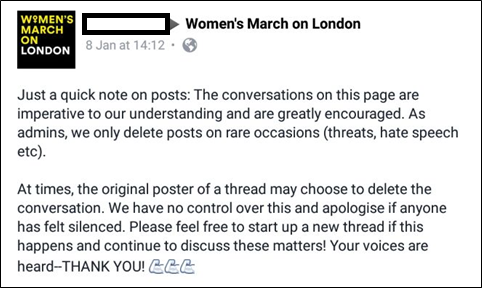

However, she pointed out that it was the authors of the posts – not the organisers of the event -that deleted the threads.

The true controversy was ignited when a tweet inviting UKIP to have a platform at the march was sent. In an effort to be inclusive, the organisers had alienated some of most marginalised women, those directly affected by UKIPs policies: migrant women, women of colour and LGBT+ women. The backlash led to the tweet being deleted.

This prompted Chardine Taylor-Stone, Founder of Black Girls Picnic and Stop Rainbow Racism, to get involved. Beforehand, the organisers got in touch with Black Lives Matter UK for support. They declined, but Natasha Nkonde – Organiser with Black Lives Matter UK, got involved in a personal capacity.

“The initial purpose of the event and guiding principles were vague and unclear – loosely based around hope,” Natasha told me. ‘Similarly to the US, it was majority white women who were involved in the planning stages so the website and Facebook were very apolitical and trying to take a neutral position. But neutral stances do not exist and they do not help the most marginalised groups.”

Inspired by the U.S. intervention, a group of women of colour and trans, and non-binary people came together to suggest improvements to the principles and speak up for marginalised women.

Chardine agreed, but admitted that the first few Twitter exchanges were heated and a difficult Skype conversation followed. It was a learning process but the end result was a positive one: “the organisers are not seasoned activists so didn’t start with a strategy. People are at different stages of their activism. They agreed to delete the UKIP tweet and post an apology on Facebook.”

When I saw the principles change so radically two days before, it hummed with the whiff of “performative wokeness” – a desperate attempt to seem inclusive. But Chardine set me straight: “the organisers reached out to a few PoC groups in November. Things fell through, as many groups are under a lot of pressure and others were not comfortable with the values and the principles of the march [at that time]. So it’s not fair to say they didn’t try earlier on.”

However, she did make it clear that they could have made more effort to research on their own and googled some more groups themselves. Both Natasha and Chardine agreed that it shouldn’t be on us to educate, but it was too important that issues such as immigration detention and trans rights were given space on the day.

So did the tough conversations and lessons learnt translate to the march itself? Perhaps. I saw many encouraging placards held by white women referencing Black Lives Matter, Audre Lorde, LGBT+ women, Maya Angelou and intersectional feminism. But mostly white faces. Chardine believes the UKIP tweet discouraged a lot of women of colour from attending: “Our Black Girls Picnic got a good response. Many joined in with our chant – ‘black rights are human rights.’ It was powerful. 5 years ago you would not have seen any intersectional signs. But it was mostly white women there – I would have liked to see more women of colour but inviting UKIP put many off.”

Natasha did not attend the March, but was in solidarity with the Movement for Justice protest in Peckham, which focused on an end to deportations and immigration raids: “I’m not going to the [Women’s] march but wanted to support my sisters and siblings who wanted to and deserved to be included. I did the work for them.”

However, not everyone I spoke to had a positive experience. Angela Camacho had a traumatic one. She is a member of the Wretched of the Earth Collective, but attended on her own behalf, as they did not support the march. Holding a sign emblazoned “The struggle within the struggle #Fuck White Feminism”, she received a hostile response from the crowd. Another woman followed her for over 10 minutes demanding an explanation as to what point they were trying to make. Two strangers warned them that they worried for their safety and they should put the sign away because some people ahead in the march were planning to snatch the sign and block them: “I didn’t want to go the march initially but I felt it was too important and white feminism had to be called out. People need to know that sometimes our struggles are different. I did not feel safe.” The sign was a critique of mainstream liberal feminism that has historically ignored issues effecting women of colour and working class women – not individuals.

Now, more than ever, we need a movement that allows us to tackle the challenges for women of colour head on. And that has the best chance of success when we have allies to support us. The march has completed its trail and our placards are in the recycling. With the difficult questions, discussions and debates ignited by the march, what happens next is crucial. Natasha believes long term organising will be key: “Will the participants in the march educate themselves [on intersectional issues], support us and connect with our groups going forward?”

I hope so.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?