When I was sixteen, my tennis coach of 10 years died suddenly. At the funeral, I sat in the back row, digging holes into my stockings with my fingernail as people read poetry, told stories and performed songs about the man who had been a second father to me. I forced myself to feel nothing.

Five years later, I watched Donald Trump sweep the election and finally understood what it meant to grieve. I lost my ideals in one stroke: my Obama-era hope that America was moving toward equality and my blind faith in the activism work I’d given my life to. I could block out the death of my coach, but I couldn’t close my eyes to the fact that my own country wanted me dead. Two days after the election, the KKK announced a “Victory Rally” in my home state of North Carolina.

I finally understand why people brought poems, stories and songs to my coach’s funeral. They had to create art in order to heal.

I sit down with three female creative of colors to discuss how they use art to grieve. They are Caribbean and Arab and Latina; Catholic and Muslim and atheist; asexual and straight and queer. But they have one thing in common: they make art in order to move forward.

“Who gets to decide what you are?” – Megan, Gastonia

Megan, a writer and painter, meets me in a new-age coffee shop in the middle of her conservative North Carolina town. It’s a liberal oasis in an alt-right desert – and, like many oases, it seems like a mirage. This coffee shop has become her safe space.

She shakes her head when she tells me about election night. “I was in denial,” she says. “I was unwilling to believe that so many people would turn a blind eye to the disrespectful and specious things Trump says… The feelings are just beginning to sink in. It will probably take me a long time to process.”

The denial has slowly given way to reality. To dread.

“I do think the election was a tragedy,” she says. “But the worst may be yet to come.”

Megan has spent her entire life navigating dualities. She is a biracial Haitian-American born in Port-au-Prince but currently rooted in the American South. She speaks Creole and French but writes fiction in English about Haitian spiritual art and Southern Gothic literature. The only constant is that she is an artist, and she has used art to capture, define and negotiate her ever-shifting identity.

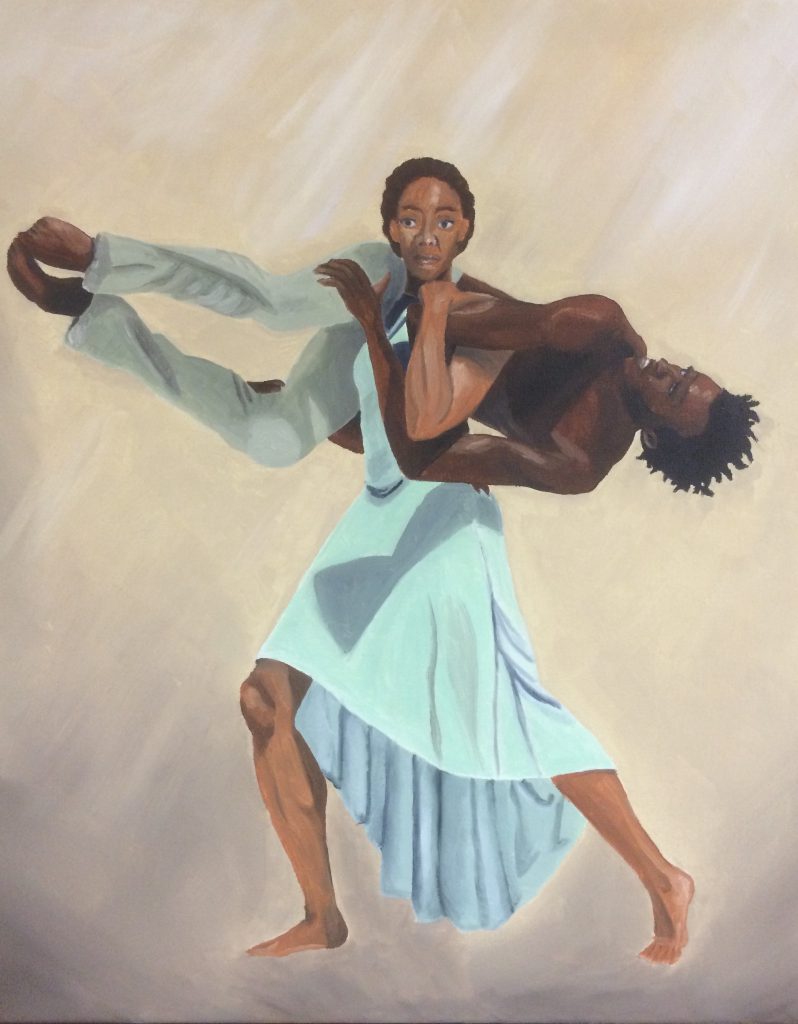

“Is it really enough to just call yourself ‘black’ or ‘mixed’ or whatever labels you choose?” She furrows her brow as she hands me her painting. “Hopefully my paintings show that there are multiple ways of being American, even if Trump’s supporters don’t want to believe it.”

Untitled, Megan P.

See more of her work LittleBrownCurly.com.

“The suffering of people like me is art, entertainment.” – Noha, New York City

Noha is a bisexual Muslim poet from New York City. On election night, she had a panic attack.

“It was less because of Trump’s actual victory,” she says, “and more because it’s a reminder of how much people in this country genuinely hate me – me and people like me.”

I ask if, like me, she has experienced something akin to grief. She shakes her head. “Terror. Or horror. But not grief. I didn’t feel like I had lost something. After the election, my father took me and my brother aside… He told me that when the government begins to condone hate crimes, it’s time to leave.”

It’s a paradox. She calls it “my country” even as she describes how it has failed her again and again. For many American women of color, we grieve not because we’ve lost our country but because we realize we never truly had one.

“My father told me that there is no Arab American and there is no Muslim American,” she says, “not in the eyes of this country. I am either a Muslim or an American.”

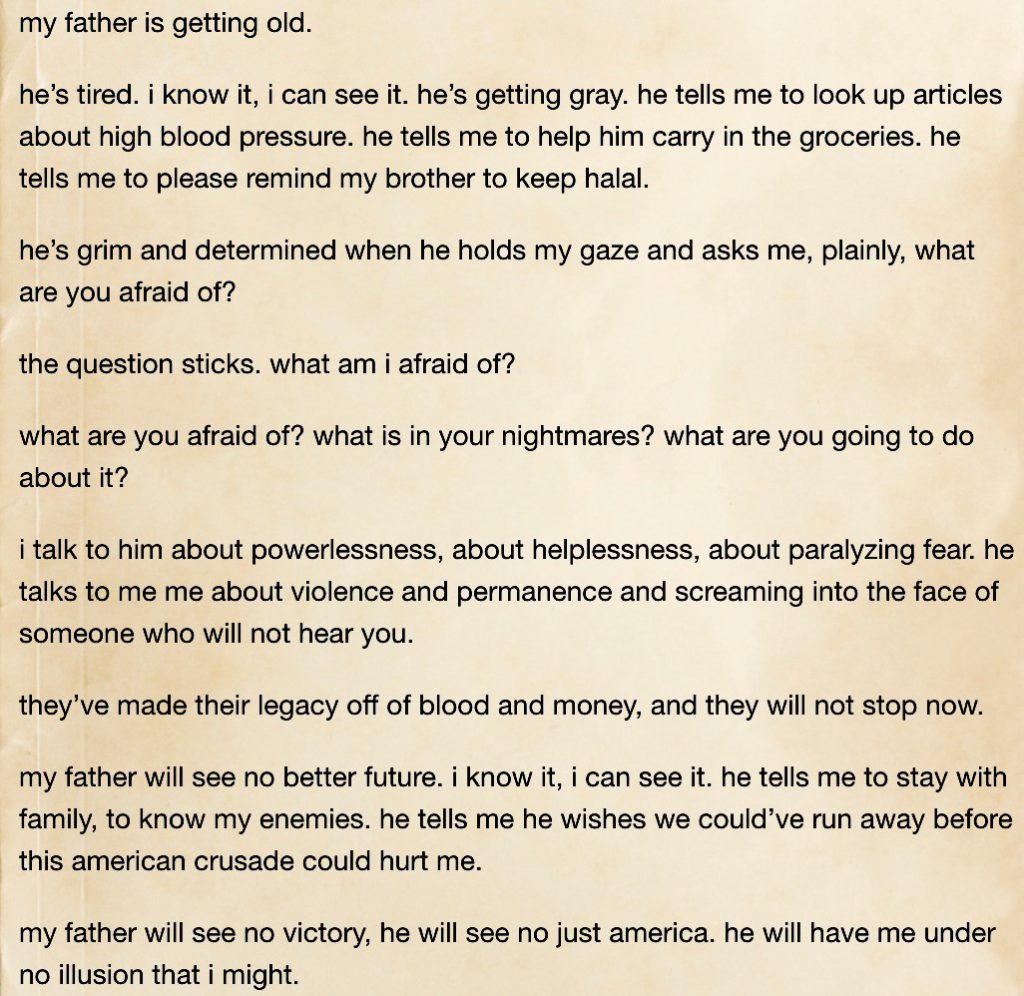

When faced with internal struggles, she defines herself by creating poetry and music. “It doesn’t exactly express the struggles,” she says, “but it does help me sort them out for myself.”

Untitled, Noha.

“No one can deny the problem anymore.” – Joelle, New York City

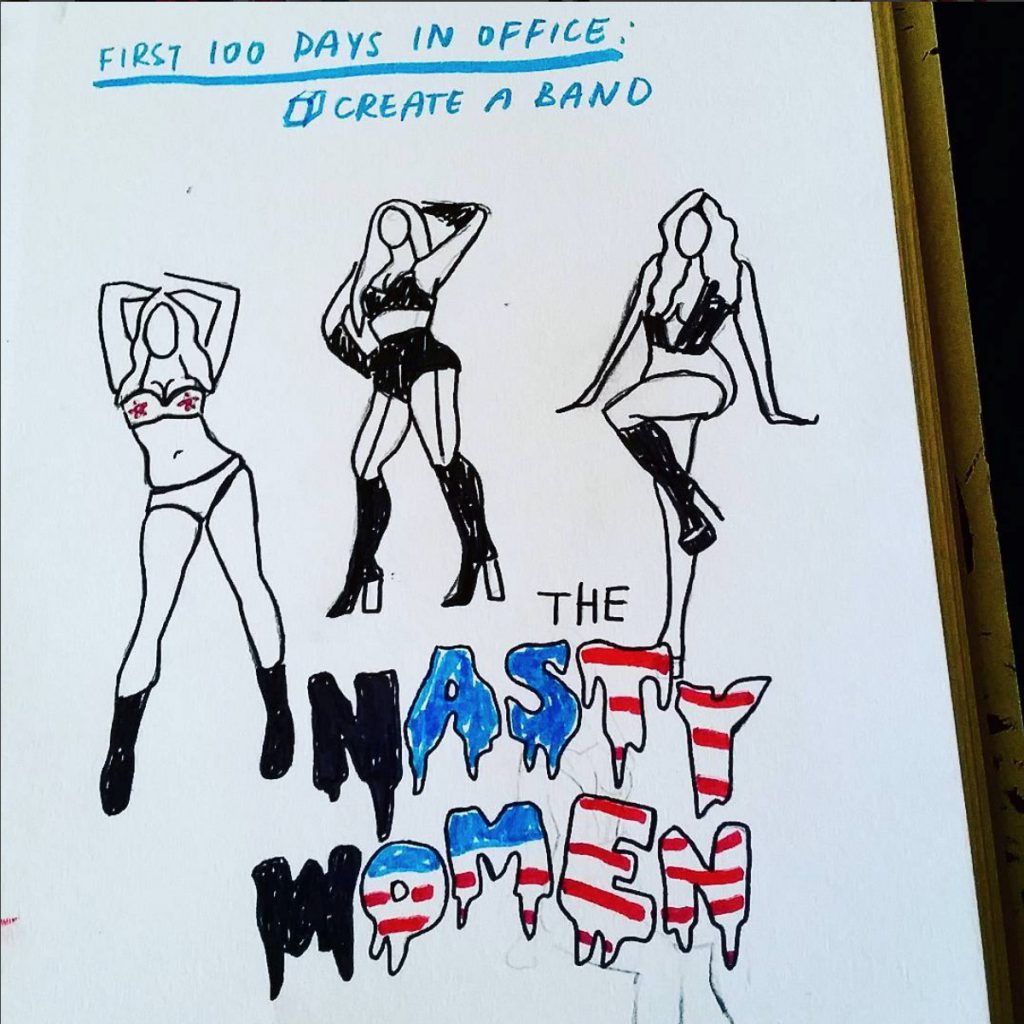

Joelle is an award-winning Cuban-American artist whose paintings sell for hundreds of dollars, but it’s a juvenile-looking sketch that catches my eye. “It was fun to portray Hillary as someone who just wants to rock out and smoke,” she says with a wink.

But the election wasn’t always something to joke about. Like me, Joelle spent November 9th wrapped in numbness and shock. “I was just going through the motions,” she says. “I have definitely experienced feelings I would describe as grief or mourning.

“But,” she quickly adds, “after one day I tried my best to look for the positives. His election exposed a problem and now it’s in full view. A light has been shone on it. No one can deny the problem anymore, which is the first step to resolving it.”

She shows me her sketch. The piece could be described as political punk rock graffiti, the type that countercultural artists use as protests all over the world, from Cairo to Moscow. If Trump actually builds his fabled wall, artists will soak it in spray paint just like they did the Berlin Wall.

She points out the faceless figures in the sketch. “It was hilarious to imagine Hillary in a punk rock band full of bad bitches. Michelle Obama is on bass, Elizabeth Warren on the drums maybe. Everyone loved to scrutinize Hillary’s personality, so it was fun to take a lighter approach.”

Joelle sees her art as an extension of herself. “Whether I’m happy, sad, frustrated at politics of whatever the case may be, art is my outlet.”

First single: when they go low, we get high, Joelle.

See more of her work here.

Megan, Noha and Joelle see art not only as a way to mourn the past, but also as a way to move forward, analyze the present and assert their own identities.

Megan sums it up best when she says, “Art holds women of color together. It keeps us from breaking. And we need that more than ever in Donald J. Trump’s America.”