Why the 50th anniversary of Barbados’ independence has been peak colonialism

Zahra Dalilah

03 Dec 2016

On a wet and windy Tuesday afternoon in Christ Church, Barbados, I ask my mum what will become of the much anticipated celebrations for Barbados’ 50th anniversary of independence, scheduled for the following day. “When the rain comes down,” she says, in the same accent that she always slips into when offering comment on her native island, “everything stops.”

She was almost right. The excitement of a day of festivities that were to feature global superstars such as the island’s best known export after sugar itself, Rihanna, had certainly been dampened by water logged fields, damaged roads and cars trapped under three and more feet of rain. But after the months of preparation for the long awaited Golden Jubilee of independence, nothing was to stop it.

“I couldn’t help but wonder to whom decolonisation means exactly what, in Barbados and beyond”

Kicking off with the unveiling of the monument which would mark the occasion, members of parliament, military service people and renowned sports men and women all streamed into the regal affair to be joined by none other than Prince Henry of Wales (aka Prince Harry himself) as they sat down for the first viewing of the architectural debut of 24-year-old Taisha Carrington.

Independence, a national holiday to celebrate the start of decolonisation and the pursuit of nationhood is of course accompanied by a supreme fête, the rum and soca which features obviously pulling in an impressive crowd of tourists. But as a group of white Americans bustled past me eager to try and get a closer look at a real life prince, 50 years to the day that Barbados declared itself free from British colonial rule, I couldn’t help but wonder to whom decolonisation means exactly what, in Barbados and beyond.

“Keen to keep the commonwealth together, the royal family are understandably eager to have some relevance in the week’s celebrations”

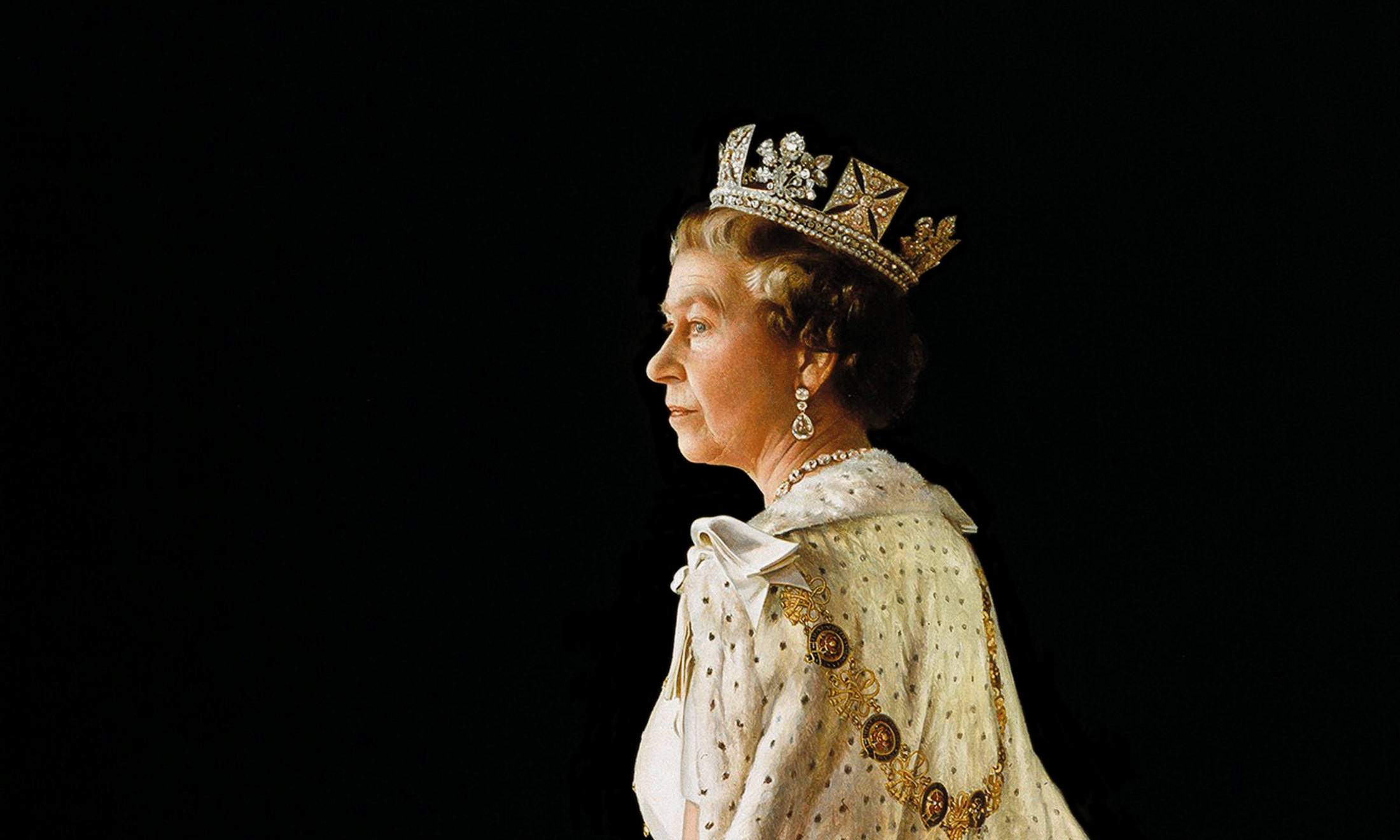

Newspaper cuttings detailing Prince Harry’s trip to the local paediatrics units to offer hugs to sick black children (whilst remaining in perfect position for photo ops), a public HIV test to promote World AIDS Day and the presentation of awards to gifted and talented youths of the island are as predictable as his presence in general. Keen to keep the commonwealth together, the royal family are understandably eager to have some relevance in the week’s celebrations, especially considering recent murmurings of Barbados finally becoming a republic and removing the queen as the head of state in the not so distant future.

Hazza’s equally predictable speech on the night harped on in the tone of colonial nostalgia that the monarchy shamelessly purports referring to when “my grandmother was here in 66” as the island began on the path to becoming a shining example of “democracy and the rule of law”. Feeling the phrase “British values” coming on I lost focus to the overwhelming feeling of nausea that was rising.

“Across what was once known as the empire, decolonisation is the daily political and economic reality”

It often feels as if decolonisation has become a buzzword, borrowed by controversial artists in ostensible black face and used to preface every institution, attitude and emotion with under or overtones of racism when calling for it’s structural change. But in Barbados, and across what was once known as the empire, decolonisation is the daily political and economic reality that seeks to transform independence from colonialism into freedom from the imperial influence of international superpowers.

Each nation has its own political context and hence a unique battle in taking the steps to that liberation. As a British-born Barbadian who has never stayed longer than five consecutive weeks on the island, I have a limited jurisdiction in regards to what economic or political decisions should or shouldn’t be made along that journey. Nonetheless listening to the Prince of Wales wax lyrical over the great nation of Barbados of which he is so proud, I recognised instantly the traditional irony and hypocrisy of the nation-state I grew up in.

When those who were quick to colonise are now quick to congratulate the rebels, activists, trouble-makers of their day for liberating the nations that they once enslaved, it is worth remembering that colonialism by a different name is reproduced daily worldwide. Economic dependence on foreign investment, political interference and the rhetoric of cultural superiority which seeps through in concepts like “British values”, these pillars of colonialism are not difficult to see in Barbados, on independence day as any other.

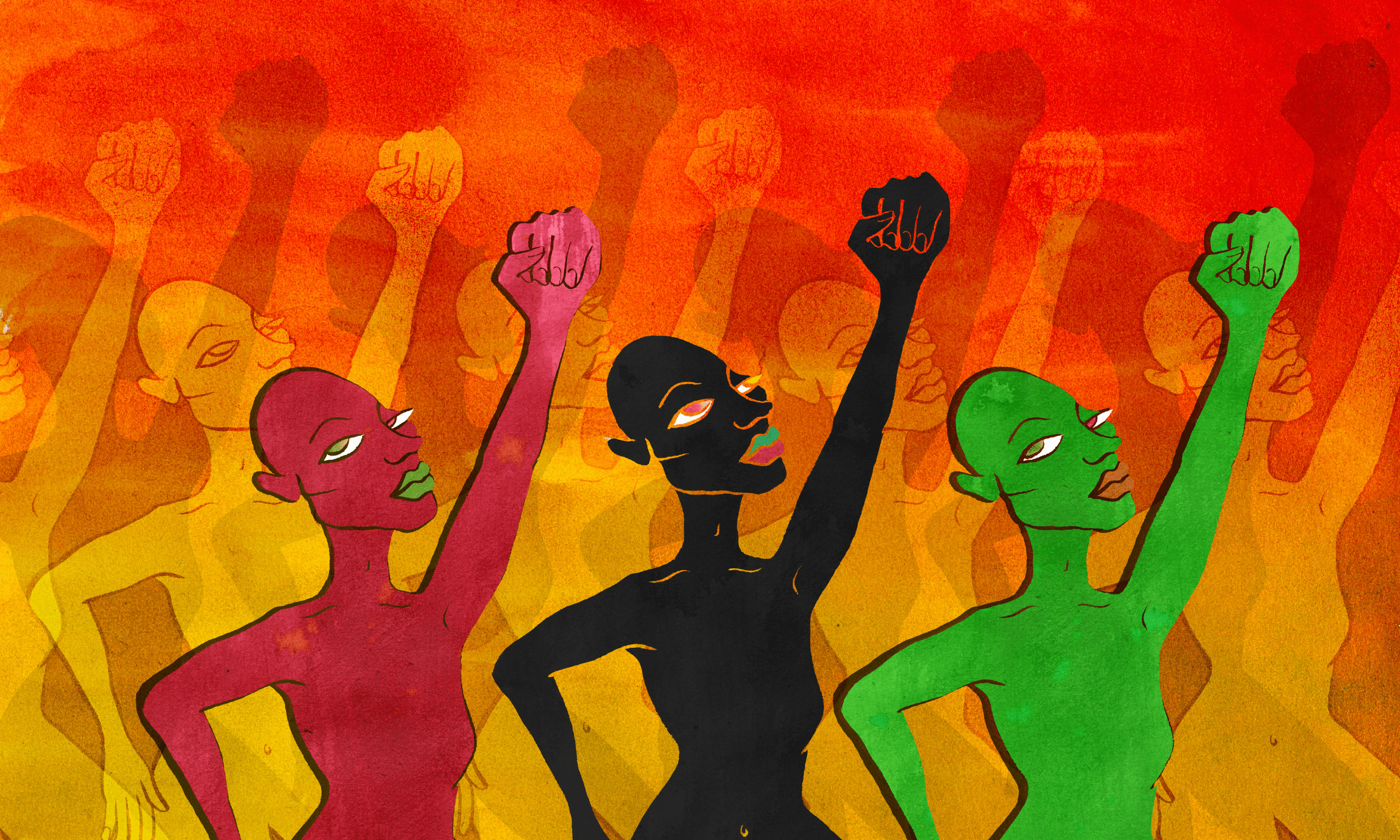

Our Anti-Colonial Welcoming Committee greets Harry pic.twitter.com/1PVCJNfEyQ

— #NotMyPrince (@NotMyPrince) December 2, 2016

Barbados, the small island that my mother left behind in 1964, is long gone. The “board houses” of wood, replaced by “wall houses” of brick and the sugar cane fields which once defined this lucrative rock in the crown have been left largely untended, hotels, bars and swarms of tourists filling the space instead. Yet, as the Prime Minister vowed last year to “complete the process” of decolonisation by declaring Barbados a republic during his time on office, as Bajan Twitter rejects Hazza’s visit with#notmyprince, the fight to decolonise Barbados, already underway during her exit, is ongoing.