On a recent trip to Jamaica my Great Aunty Girly told me that she didn’t think she would see the rest of her family again before she died. Out of almost a dozen siblings she was now the only one left alive in their mother country. The rest were scattered – some in America and Canada, but mainly in the UK. Speaking about my Nanny (Grandmother), Teneta, she told me that she longed to see her again. “My heart hurts for her,” she said, “I didn’t really grow up with a sister.”

The Windrush Generation is a poetic descriptor for the influx of immigrants that came to the UK from the Caribbean Commonwealth countries in the mid-20th century, including my Nanny. MV Windrush, a passenger liner and cruise ship originally launched in Germany in 1930, was the first boat to arrive in Britain with Caribbean immigrants after WW2. It brought nearly 500 people to our grey shores in 1948 and, in time, thousands more followed – the UK government pushed for the immigration after losing so many “able-bodied” men during the war. Now those original immigrants, who represented the first non-white mass immigration to a country which, up until the 1940s, was almost completely racially homogeneous, are our grandmothers, grandfathers, great-aunts and uncles, cousins and friends.

My Aunty Girly explained to me that Teneta had left for England as a young woman, 18 or 19 perhaps, when she was in her late teens. She wasn’t one of those on the Windrush boat, but she did travel to the UK less than 20 years later, in 1960. She lived with a bodybuilding uncle named Appy, before meeting my Granddad and becoming a bus conductor.

However, the 21st century marks a change in the relations Caribbean people have with the UK. While the number of black people in the country overall is growing, the Caribbean community is essentially shrinking. In 2001, it outnumbered the African population but there has been a significant reversal. Between 2001 and 2011, those who identified as black Caribbean stabilised. The black African population, on the other hand, has doubled from 484,783 to 989,628 nominally. For better or for worse, we are “assimilating” into Britain through mixed-race relationships (43 percent of black Caribbean people were in a mixed-race relationship, compared to 22 percent of black Africans in 2011) and lower rates of immigration.

The original Windrush Generation is also, sadly, dying out. While there have been documentaries, such as the BBC’s eponymous Windrush, which marked the 50th anniversary of the boat’s journey, the voices of men are usually centred. As the narrator explains, most of the passengers on the original boat were ex-servicemen seeking work. But, later, women did come too – taking the 10-day boat journey across the Atlantic sea – and I have always been interested in the stories of those who were brave enough to make the journey.

***

Last year, Catherine Ross and her daughter Lynda founded the National Caribbean Heritage Museum, in part to help document the Windrush Generation’s experiences before it’s too late. Ross and her family moved to the UK from the island of St Kitts when she was seven years old in the 1950s, following their father who had settled in England a year beforehand to prepare for their arrival. One of the most interesting projects they’ve worked on so far is “Stories in a Suitcase”, an exhibition exploring what the Windrush Generation brought with them to the UK. This included mock-ups of luggage brought by women and young girls, using 1950s-70s charity shop items collected by Ross in the years beforehand.

“They’d pack their suitcases with their best outfits which would invariably be nylon or flimsy material and then it would be the wrong time of year,” she explains. “It’s an exaggeration to say they froze to death, but you know what I mean. They’d wear two lots of everything in order to keep warm. Some people came with as little as they could because they wanted to start afresh. Others came with things they intended to work with. As we’re a very religious people, some brought things of religious significance like a bible or a hymn book.”

In the exhibition, which has been on tour at different parts of the country, the suitcases show an assortment of essential Caribbean items: recipe books, boxes of “Canadian Healing Oil”, hair styling products and lacy gloves. Ross says that for many Caribbean women, the natural path their careers took were as hairdressers, dressmakers, healthcare workers or on public transport. But, I wondered, why did the women want to come to the UK in the first place? Unlike many of the men who had visited the UK during the war before deciding to make the move, Caribbean women tended to be more sheltered. It was unlikely they would have ever left their respective islands before embarking on their voyage overseas.

“Most people were young, I don’t think anybody was over 30 really, and they all came to work, for a change of career, or they came to study and further their career,” says Ross. “In the main everybody was vibrant, energetic and were able to do three jobs; able to work long hours. The people who moved over were the cream of the crop.”

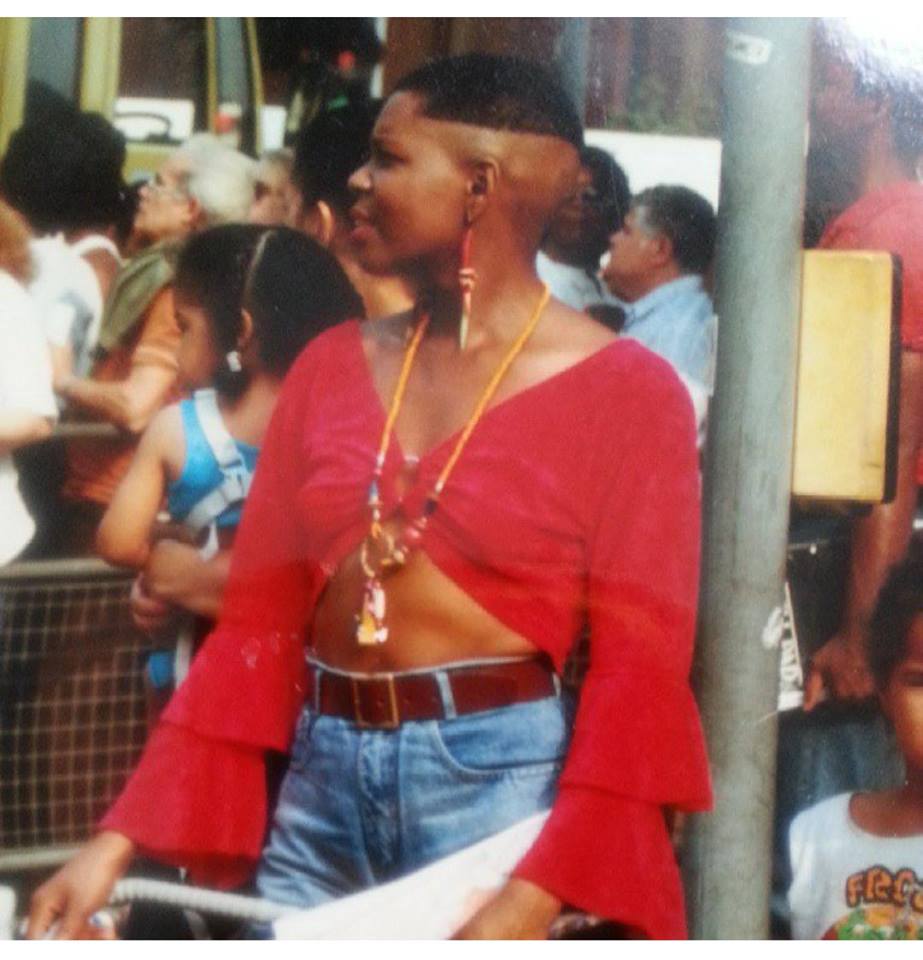

Joyce Barrett, 74, was one of these women. She left for England from Jamaica in April of 1961 aged 19. A tall, slim woman with an eye for style and “dripping in sophistication” according to her granddaughter Heather Barrett, a fellow gal-dem, she didn’t bring anything with her apart from a small suitcase filled with clothes.

“I left for a better life because that’s what everyone was doing; looking for a better life for themselves,” she says, “Things weren’t right in Jamaica. As a young girl I wanted to travel and people were going over to England so I went too. I travelled over with a friend’s niece, but unfortunately my friend is not with us anymore. He got elected to government and when he was celebrating that night in Jamaica he was poisoned.”

Heather tells me that like many Caribbean women, Joyce became a nurse when she moved to the UK, and as a second-generation immigrant like myself, her upbringing around her grandmother sounds familiar.

“When I was really young, her thick Jamaican accent would sometimes baffle me and I would nod my head in the hope that, yes, she had just offered me another dumpling. Then years later I remember singing songs to her that I learned from a book of Caribbean nursery rhymes so that I could show off how good my Jamaican accent was getting,” says Heather. “I also remember playing with stethoscopes she had hanging on the walls that she acquired while being a nurse in Lewisham.”

The government invited many Caribbean women to the UK to work as nurses as the need for health workers was significantly increased by the creation of the National Health Service (NHS) in 1948. In a Heritage Lottery funded project to collect the stories of retired Caribbean nurses from 1949 to the present, which exhibited at Hackney Museum last year in collaboration with Black Women in the Arts, their contribution to the fabric of the National Health Service is made clear.

“We realised that many of those nurses, now in their 70s, 80s, who arrived in the 1940s, early 1950s, were on the next stage of their journey. They were dying, or leaving the world as it were, without their stories being recorded,” says Beverley Davis, project manager of the exhibition. “The main things that came across were their commitment to the profession, their willingness to learn new things and their bravery for actually arriving in a country that was so different to the countries they came from. It was very cold, the food was very different and the people that they met didn’t necessarily respond to them in a positive way. Often the patients weren’t very warm and welcoming.”

Strangely, one of the schemes to recruit Caribbean women to the UK as nurses was headed up by Enoch Powell, who was the Tory Health Minister between 1960 and 1963. Five years later in 1968 he became known for his “Rivers of Blood” speech, given at a Conservative Association meeting in the Midlands – an area which saw steady levels of immigration from the Caribbean. In it, he described the imagined deterioration of race relations in the UK and the “cloud no bigger than a man’s hand, that can so rapidly overcast the sky”, of immigrants that he believed were causing problems.

“As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see the River Tiber foaming with much blood,” he said, and in one fell swoop helped to foster much of the racism and anti-immigration sentiment that had been brewing in the years since the Windrush Generation first came to the country. Many immigrant nurses say patients refused to be treated by them because of racist ideologies.

“I guess it’s ironic really,” says Davis. “In politics people do what’s needed in the moment and then change their ideas or their thoughts along the line. If you speak to young people now they don’t know who Enoch Powell is, but when he was alive, with some of the things that came from his mouth you would not have believed he was one of the main ministers responsible for that recruitment. At the time Britain needed a cheap labour force.”

***

Although Joyce says that she didn’t face any racism when she moved to the UK – “I think I was too pretty,” she laughs – Heather believes the story is more complex. “Although she stays relatively quiet about much of her past, I am wise enough to know that if she’s avoiding answering something, it’s probably because she doesn’t want to talk about it,” she says. “I am not about to add to the negative narrative of black women; I will not press her to expose her scars and struggles for the sake of my curiosity.”

And for others of the Windrush Generation the story is openly bleak. Race riots have punctuated UK history since the mid-20th century and, in 1958, commotion broke out after a crowd of white men attacked a Swedish woman because she was married to a black Caribbean man. In the Bristol Bus Boycott of 1963, Bristol Omnibus Company refused to employ black or Asian bus crews. The 1964 slogan, “If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour” used by a Conservative politician during an election in Birmingham, fostered more anti-immigrant sentiment. And while many of these incidents have been sparked by the death or mistreatment of black men, almost every Caribbean woman I speak to has witnessed overt racial prejudice and ignorance too.

Cheryl Pearce, 62, who came to the UK from Barbados in 1964 when she was 10 years old, says that, for her, it was at school where she first realised there were problems: “I remember a teacher had put on display a piece of work which said that black people lived in treehouses or mud huts because we were monkeys. Luckily there was one black prefect in the school who marched to the head teacher’s office to complain and get it taken down,” she says. “I thought it was so stupid.”

Everine Shand, 56, from Jamaica, moved to the UK at a similar age in 1972 and says she also remembers being called racist names at school: “I didn’t understand and thought the white kids were just being friendly,” she says. “It was later when I made friends with the few black kids that were at the school I began to understand that these white kids were making derogatory remarks.”

When she had been at the school for a little while, Shand made friends with an English girl from her class, named Sheree. But when she would go round to the girl’s house before school, Sheree’s mother wouldn’t let her in: “She looked at me with sadness in her eyes, and said, ‘Everine, I’m sorry but you can’t come in’. I didn’t think much of it at the time, I just waited for Sheree and I continued to call for her each morning. I’d just knock and move away from the door. It became apparent years later that her Dad was racist, and had instructed his wife never to invite me into their home. Sheree was also told to stop mixing with the likes of us, but she flatly refused.”

***

In Brixton, where the Caribbean community is valiantly fighting against gentrification and the “temporary” closure of the railway arches, hundreds took to the street for the Emancipation Day March at the beginning of August which started at Windrush Square. The voices of women were loud: “The government needs to address and acknowledge what’s happened in the past,” one woman told the Evening Standard, wearing slave chattel-like chains around her neck. “We are suffering from post-traumatic slavery syndrome and post-traumatic slavery syndrome as a result, a direct result, of colonial slavery – and the colonial debt is still imposed on our countries, on our families today.”

The journey across seas from west Africa to the Caribbean and then to the UK hasn’t been an easy one. It has left scars on the women who bore the weight of racism and prejudice on their backs. As put by Claudia Jones (a woman who founded the first major black newspaper in the UK, The West Indian Gazette) in a 1949 article called ‘An end to the neglect of the problems of the Negro woman!’, “From the days of the slave traders down to the present, the Negro woman has had the responsibility of caring for the needs of the family, of militantly shielding it from the blows of Jim-Crow insults, of rearing children in an atmosphere of lynch terror, segregation and police brutality, and of fighting for an education for the children.”

And that legacy will continue. As Black Lives Matter protests pop up around the country – almost all organised by gals like ourselves – the women of the Windrush Generation can rest easy. Our future is in good hands and we will forever be grateful for the suffering they went through on our behalf.