“You have big muscles for a little girl!” And so it began. These words, from a ginger boy in the year above me in primary school, said as he pinched one of my small brown arms between his freckle-speckled thumb and forefinger, kicked off a paranoia that I carried with myself for the next ten years.

I’ve never been one to accept my flaws. I’m stubborn about most things and the insecurity that rushed through me as a teen was something I actually found difficult to comprehend. How could I feel this way about myself? Why did I feel the need to cover my arms and shield my thighs by wearing skirts rather than skinny jeans? I was questioning the idea that I could have flaws while actively admitting them into my consciousness and letting my hatred of them take over core aspects of my life. My skin colour and body made me feel so large, imposing and unfeminine that I tried to avoid any form of weightlifting – from shopping bags to the gym. I would stare at my body in the mirror for hours, squeezing the places where I hoped it would shrink into submission.

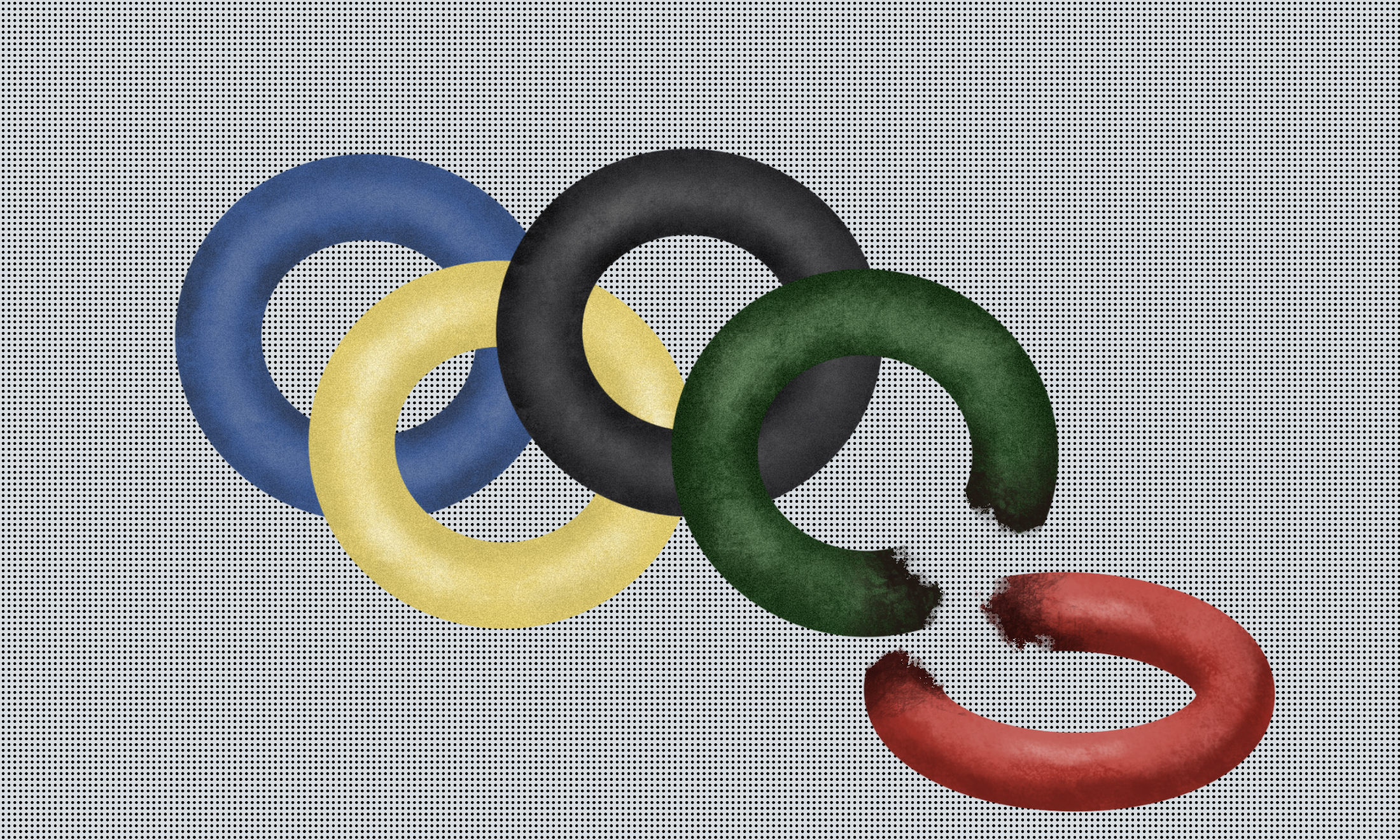

But, watching events like the Olympics, especially sports like track and gymnastics, has helped over the years. As I wrote about Serena Williams a few months ago, there’s nothing that increased my body confidence more than seeing people like her, who actually resembled me, looking beautiful, powerful and successful. And as the clean-up from the games in Rio begins, I can’t help dwelling on why my insecurities came to manifest, and how – throughout this Olympics in particular – the scrutiny of muscular, “larger” women of colour has permeated too much of the rhetoric. From the widespread, racially-charged condemnation of South Africa’s Caster Semenya, the women’s 800m champion, to the cruel comments levelled at Mexican gymnast Alexa Moreno, it’s been a terrible year for misogyny, misogynoir and the dehumanisation of black and brown bodies.

“Why did I feel the need to cover my arms and shield my thighs by wearing skirts rather than skinny jeans?”

Just yesterday Polish runner Joanna Jozwik said that she was proud to have finished as the “first European” and the “second white” in the 800m race. Jozwik added that, “The three athletes who were on the podium raise a lot of controversy. I must admit that for me it is a little strange that the authorities do nothing about this… These colleagues have a very high testosterone level, similar to a male’s, which is why they look how they look and run like they run.” Comparably offensive comments were made by Italian gymnast Carlotta Ferlito, after Olympic champion Simone Biles (#Queen), became the first black woman to win the gymnastics world championship in 2013. “Maybe next time we’ll paint our skin black so we can win,” she said. As put by Paula Akpan and Niellah Arboine, writing for gal-dem, “By focusing on their looks, these women are treated like freaks because their bodies do not present femininity and womanhood in a way that we are used to, or is deemed acceptable enough.”

While this isn’t a problem unique to women of colour – with black women too often homogenised as having large bums, thick thighs and bigger features – there is no getting away from the fact that my body fits quite neatly into the stereotype that has been perpetuated about black bodies since colonial times and the awful, circus-parade that was Saartjie Baartman’s life. Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman from southwestern Africa, was born in the 18th century and exhibited as a freak show in the western world due to her “steatopygia” – a so-called “condition” which saw her have particularly large thighs and buttocks. After her death, visitors to the Museum of Man in Paris could view her brain, skeleton and genitalia as well as a plaster cast of her body for over 50 years. Her legacy, through no fault of her own, is a world where black women’s bodies continue to be seen as exotic and abnormal.

The bravery that women like Moreno, Semenya, Biles and Dutee Chand (another runner who, like Semenya, has hyperandrogenism) have shown in continuing to compete with grace in the face of negative comments, especially those from fellow competitors, is inspiring. It is their demeanour I hope to emulate when I continue to play the sports I have always loved – football and cheerleading. The internal battles are still there – especially after a year of cheerleading, which essentially involves months of weightlifting and cardio and sees my body build muscle quickly. I still have to remind myself that being fit and healthy and, yes, muscular, doesn’t make me any less of a woman than girls who are more petite. Being called, intermittently, “hench” and a “tank” by friends and acquaintances hasn’t helped. It’s all too easy to say that I should ignore the paranoia I have about my body’s “inadequacies”, but in our society so much emphasis is still put on appearance that your self-worth can very easily become impeded if you fail to meet expectations of beauty.

“Baartman’s legacy, through no fault of her own, is a world where black women’s bodies continue to be seen as exotic and abnormal”

Despite this, as the sprinkling of #BlackGirlMagic seen in the women’s 4x100m relay – which saw all nine medals going to black women from the United States (gold), Jamaica (silver) and Great Britain (bronze) respectively – displayed, being and looking physically strong is nothing to be ashamed of. While there are still things I don’t like about the way I look, my strength isn’t one of them. It’s meant I can run a 10k in under an hour, having only been running four times in my life. It’s made me a strong base in cheerleading, and a good gymnast. It’s meant I’ve been able to hike in the mountains of Costa Rica, jump off cliffs in Jamaica and swim in the rough Pacific sea. How could I continue to dislike it after all of that?