A recent article by the Guardian revealed that police forces continue to abuse their stop and search powers. In fact, 13 of the worst offending forces have been removed from a “best use of stop and search” scheme by the home secretary, and a further 19 have also been told to improve else they will be publically shamed. The lead inspector of Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (inspectors of the police forces of England and Wales) has stated “Every single major report into disorder in this country since 1970 places stop and search as one of, if not the most important contributing factor, and those lessons need to be learned.” So, what does this history consist of and why is stop and search such a problem?

Stop and search, as the name suggests, gives the police the power to stop and search someone on the street if they have reason to suspect they are carrying illegal substances, a weapon, stolen goods, or tools to commit a crime. It was originally implemented to tackle an abundance of violent crime and to “keep our streets safe,” however it has led to a great deal of controversy and has been subject to public scrutiny since its inception.

An inquiry into the Brixton Riots of 1981 blamed the conflict between police and protesters on the disproportionate use of stop and search against the African-Caribbean community. This led to the release of a new code for police behaviour and the introduction of the Police Complaints Authority (to replace the Police Complaints Board), which had increased powers and a fresh new title.

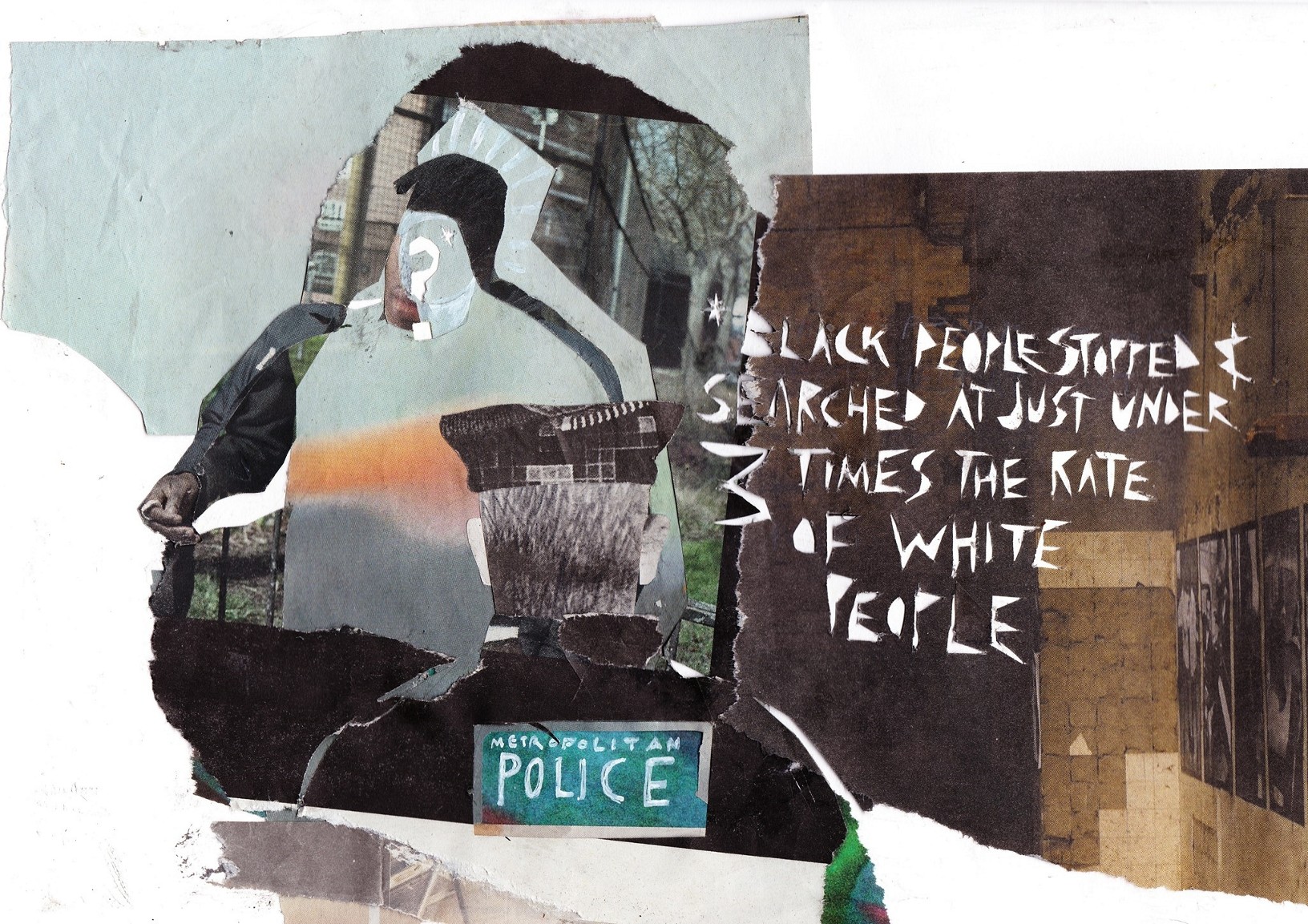

Fast forward almost 30 years and not a lot changed. Although police officers needed to have a good reason to stop and search anyone, it soon became evident that black people were stopped and searched at just under three times the rate of white people* across London. Plus with only 16% of these actually leading to arrests, anger quickly spread among communities of ethnic minorities who deemed stop and search as thinly veiled institutional racism. A low arrest rate meant that instead of helping with crime prevention as intended, stop and search was putting a bigger strain on young people and communities whose rights were repeatedly violated.

In response to this controversy, the government finally held consultations on stop and search powers discussing how they could be used more “fairly” and “effectively.” They spoke of more, better, training for officers, and tightening the grounds on which they could stop and search someone. They also increased public awareness of a person’s rights during a stop and search and guidelines informing you how to act if it does happen to you. The idea of this was to allow stop and search to continue with less public slander and to help fix the tarnished reputation the police had among communities they had discriminated against, but it only confirmed that in order to not be arrested during a stop and search you should “act a certain way”.

A November 2015 report revealed that police in London currently have an arrest target for searches set at 20 percent. But of the 32 London boroughs, only 12 have managed to reach this target. While a marked improvement from previous years, is this figure high enough to justify the searches? Additionally, teenagers are targeted the most despite being the least likely to be found with anything, whereas adults in their late 20s are targeted the least but are the most likely to be carrying something. The police’s relationship with youth is turbulent and unsettling as it is. Introduce stop and search and that relationship depletes into nothing. While many young people can understand the little good that does come out of them, stop and searches remain the key point of contact between police and youth. These searches can be stressful, tense encounters and a lack of respect for police increases every time a young person feels their freedom and personal space has been violated. In fact, whenever any person young or otherwise is searched, the police are inferring that this person is up to criminal behaviour, ergo dubbing them a criminal. This is where the distrust of police stems from and a mutual lack of respect on both sides creates an ‘us’ and ‘them’ situation.

Furthermore, considering that the population of ethnic minorities in London continues to rise, you would think that the Metropolitan Police would be recruiting a more diverse range of officers to represent such a multi ethnic society. Alas, there has been a drop in proportion of Met police recruits from ethnic minorities. This under-representation does nothing but increase the divide between community and police, and is especially prevalent in areas with a less ethnically diverse population. In the largely rural county Dorset, for example, black males are 17.5 times more likely to be stopped than their white counterparts – an unsettling statistic.

Stop and search has had an unprecedented impact and it is up to the people to fight the systematic injustice it promulgates. Such negative experiences at the hands of the very institution intended to keep them safe leaves black and minority ethnic groups feeling ostracised. Are we not part of the society entitled to protection?

Those suspended from the scheme by the home secretary are Cambridgeshire, Cheshire, Cumbria, Gloucestershire, Lancashire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Northumbria, South Wales, Staffordshire, Warwickshire, West Mercia and Wiltshire.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?