The Good Immigrant: encapsulating the experience of not-quite-belonging in Britain

Charlie Brinkhurst Cuff

22 Sep 2016

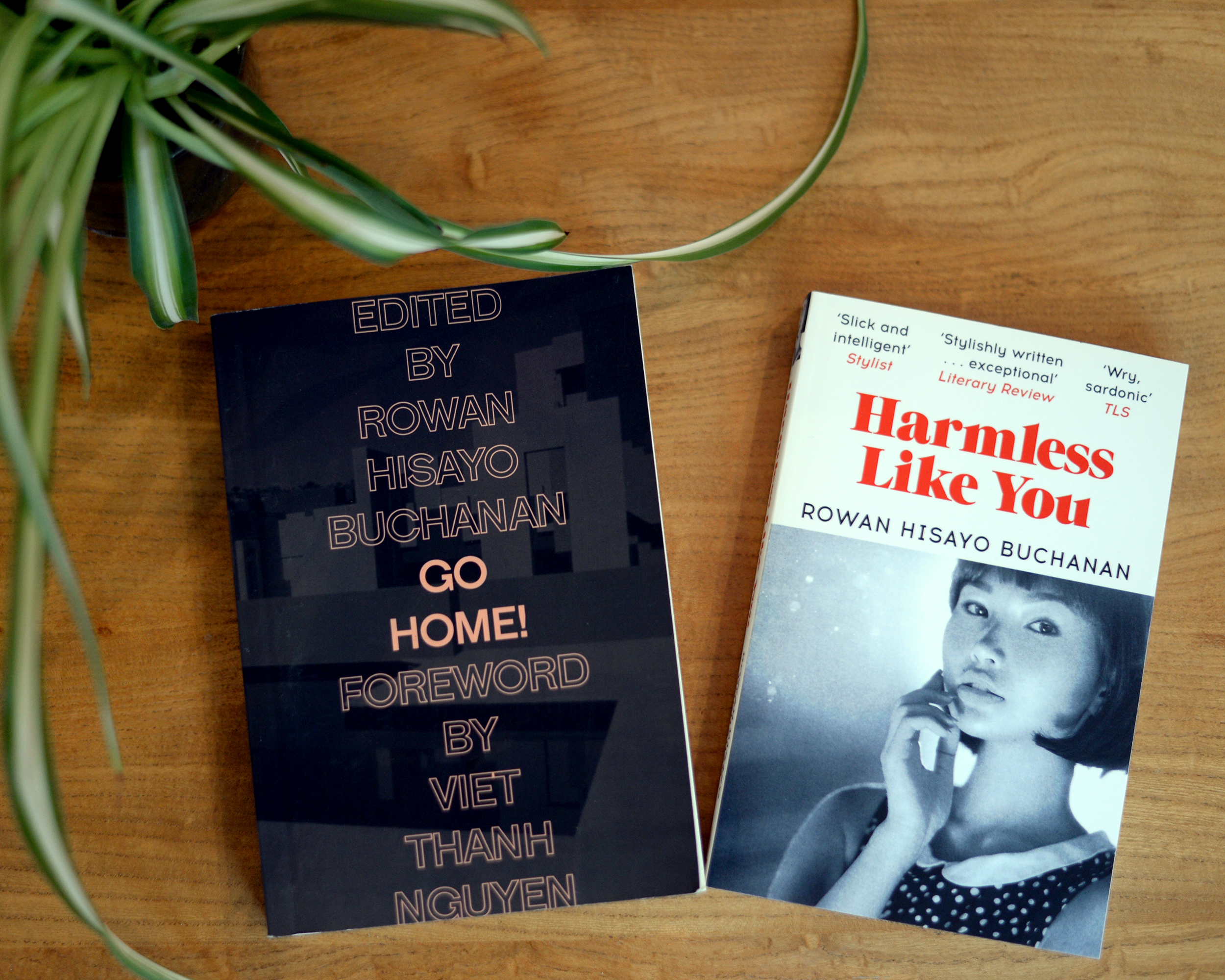

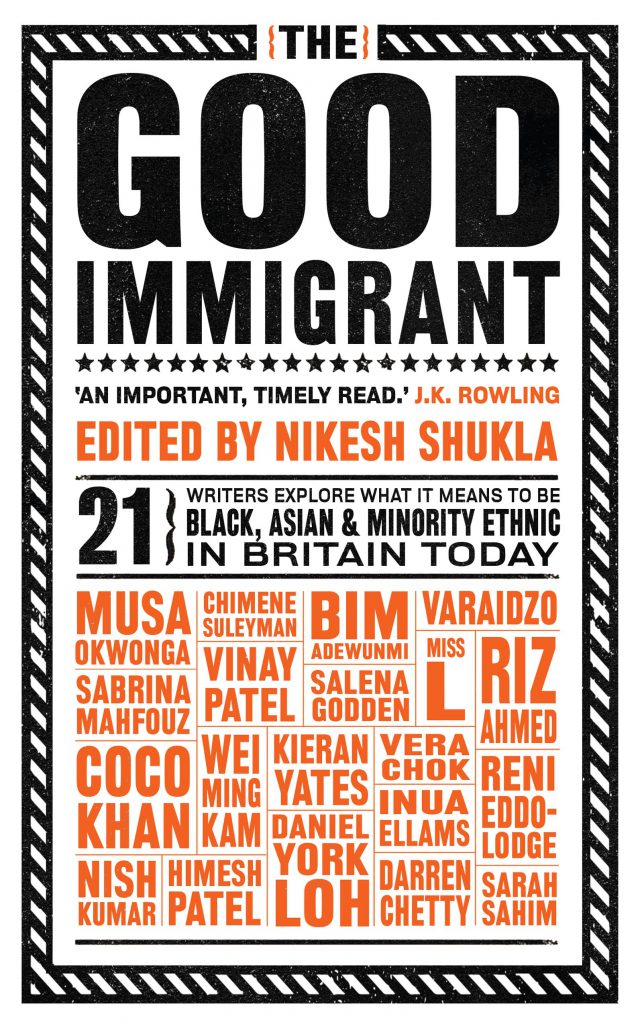

If you are not an immigrant, or the child of an immigrant, you might not understand this sentiment, but to me, The Good Immigrant (ed. Nikesh Shukla, launching today, September 22), reads like a lullaby. It is soothing in the way it encapsulates my lived experiences; making me feel less alone with more permanance, eloquence and creativity than many of the equivalent essays I have come across elsewhere.

The Good Immigrant was always going to be special. A crowdfunded anthology of essays on race and immigration, it was supported by JK Rowling, who tweeted back in December that she believed it would be “an important, timely read”. The book then reached its funding target within three days and, so far, has been positively reviewed in the Guardian, The Spectator, and Newsweek.

The final product features some of gal-dem’s favourite, young WoC writers such as Reni Eddo-Lodge and Kieran Yates – who we recently interviewed for gal-dem’s upcoming print issue (pre-order here) – along with others, including poet and writer Salena Godden, comedian Nish Kumar, teacher Darren Chetty and, of course, our very own arts and culture editor, Varaidzo. These are essays which aren’t afraid to lay bare the brutality of treatment that you can recieve as a person of colour in the west, and intimately document the unqiue struggles with identity that we face.

Yates’ ending statement in her essay ‘On Going Home’, particularly resonated with me: “We’ve never really been split, never been cut in half, we’ve just been silent about how we’ve been empowered because we haven’t always felt it, have been too busy being good immigrants, not making a fuss, and quieting down when people felt uncomfortable,” she writes in a call to arms. There is hope amongst the uncertainty of our identities, she explains.

Actor and rapper Riz Ahmed’s piece ‘Airports and Auditions’ – recently previewed in the Guardian – was another stand out. Having watched Asian friends go through the indignity of being visciously questioned and searched by border police (“I have had my films quoted back at me by someone rifling though my underpants, and been asked for selfies by someone swabbing me for explosives,” Ahmed writes) his metaphor which threads through the essay, of a constricting necklace of labels handed to you as a minority, “neither of your choosing nor making”, will ring true to many.

And Nikesh’s essay, ‘Namaste’, of course, one of the rawest in the anthology, which opens with a strict take-down of cultural appropriation and broadens into the effect that bastardising someone else’s culture can have; on navigating his life with not one, not two, but three voices: “I talk in Guj-lish, my normal voice and white liteary party. I don’t know whether my normal voice, where I feel most comfortable, most safe, even feels like me anymore. I’ve splintered into personas.” It’s potent and quite beautiful and I would encourage you all to buy a copy.

An exclusive extract from Varaidzo’s essay ‘A Guide To Being Black’, from The Good Immigrant:

1. Black is the New Orange: Explaining the ‘One Drop’ Rule

I first acknowledged that I was black in the back seat of my best friend Jenna’s car… [My] post-racial utopia dissolved when I was sent to a primary school in Bath and I was the only brown-skinned child in my year. Around the same time I developed an obsession with the colours red and yellow. My bedroom had pairs of red and yellow walls, and I exclusively used those crayons to scribble. I understood how these colours interacted, that if combined they created a new colour: orange. I applied this logic to my own family. With one black parent and one white, I was the orange to my father’s red and my mother’s yellow, not quite either but rather something altogether new.

Does an orange thing ever stop to think that it might actually be red?

I never had reason to consider I was anything other than mixed-race. Until the car journey. Jenna sat back in her seat and grinned, triumphant that she knew more about the world than the other children in the car.

“I’m mixed-race, actually,” I mumbled, trying not to draw the entire car’s attention to what I was or wasn’t. And Jenna, relishing her new found state of knowing everything, rolled her eyes and crossed her arms.

“Well, obviously,” she said. “But you’re still black. That’s just what we’d call you.”

She was right, of course. As a term, mixed-race could never fully illustrate my experiences. It described nothing; the act of being not one thing or another. To be a mix of races is to be raceless, it implied, and yet that had never been my reality.

My race was distinct and visible, the thing that defined me as different to the rest of my classmates. Mixedness alone couldn’t describe this difference. Blackness was something more convincing, more tangible. It spread out across my features in big lips and long forehead and hair that grew out rather than down. It filtered through me like a beguiling beckon, drawing security guards towards me when I entered a store and tricking my teachers into thinking I could outrun anyone. The world saw blackness in me before it saw anything else and operated around me with blackness in mind.

There was a drama to blackness, a certain swagger and verve, an active way of experiencing and being experienced that mixedness could not accommodate, one that I was committed to embodying fully… There was one thing I’d never considered about mixing red and yellow: a drop of yellow into red paint won’t do much to change the colour, but one drop of red into yellow and the whole pot is tainted for ever.