Tamika Cross and why black female doctors are still having to prove themselves

Annabel Sowemimo

23 Oct 2016

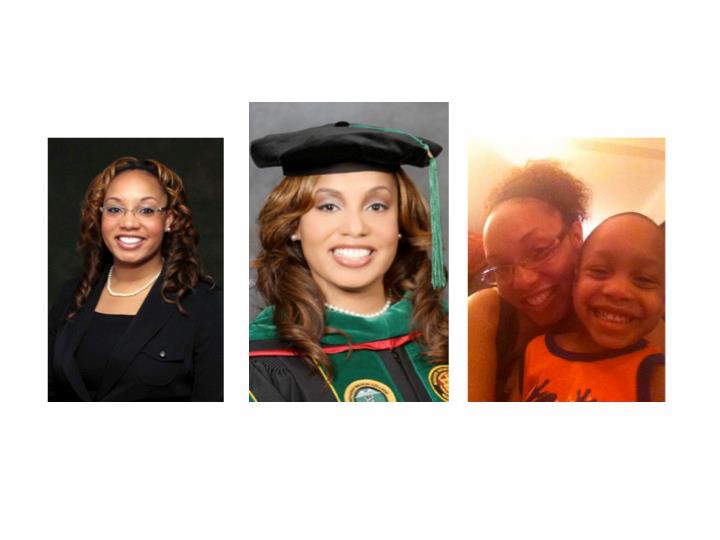

Just over a week ago our timelines were filled with reaffirming images of black female physicians utilising the hashtag #WhatADoctorLooksLike in response to the alleged discrimination faced by Tamika Cross onboard a Delta Airways flight. Tamika Cross, a resident obstetrician in Houston, Texas, tried repeatedly to respond to calls for a doctor when a man a couple of rows behind her became unwell. She states that each time she tried to explain she was a doctor the air hostess was dismissive, eventually asking her to produce her “credentials”. When a white, male physician offered his assistance it was accepted without further questioning and he provided the patient with assistance. The air hostess offered Dr. Cross air miles as an apology which she refused and has since complained to the company; Delta are currently investigating the incident. The air hostess’ discrimination was so blinding that a man’s life may well have been put at risk.

Had it not been for Dr. Cross’ confidence in speaking out then she may well have gone home, curled up on the sofa and cried about the injustice of it all. I’ve written about my own experiences as a young, black female doctor but I am well aware that such situations extend to women of colour in a plethora of work environments. Too often I have heard from friends and family working within corporate settings that disparaging remarks about black or brown people are made in their presence but they refrain from speaking out, for fear of fulfilling “the angry, black women stereotype”. One friend who works in banking has to regularly put her hair in back to back weaves for fear of work colleagues seeing her natural hair. The daily exposure to the working environment is a form of structural violence for many black women.

Historically black women have been characterised as either “the carer” or the “hyper sexualised being”, neither of which have any role in the modern work place. As industries evolved in our absence, they were not built with black women in mind. In the US the National Centre for Education Statistics revealed that black women have the highest proportion enrolled in college than any other group. They were not prepared for the magic that we were waiting to unleash. Despite globalised images of Michelle Obama in the White House, incidents such as that on the Delta flight show that attitudes towards black, professional women have been slow to shift. We remain alienated in our places of work, that were never created with us in mind. We shrink ourselves to conform, blend in and hope that this will be enough for us to get by.

The feminist legend Audre Lorde said: “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.” We have come to accept that the world is hostile to our presence. I remember a lecturer suggesting that a course may be too demanding for me, rather than risk being seen as “angry” I fell silent and went home to my family in a bad mood.

We internalise these feelings and often fail to notice how exhausted and angry it is making us. Worse still we are not allowed to articulate that anger for fear of fitting the nightmare stereotype. We are not allowed to be exhausted because society has come to expect us to be strong, fierce (but not angry) at all all times. We are constantly in some strange, unobtainable yoga pose as we try to please everyone. In Sisters of the Yam, bell hooks states how the oppression experienced by black women manifests itself in poor physical health. It is no surprise that black women battle with record numbers of depression, hypertension and obesity as we internalise the societal pressures that are constantly unleashed on our lives.

What the hashtag #WhatADoctorLooksLike symbolised was a beautiful moment for black women as we strike back, acknowledging our fellow sisters struggle and act to help her heal. Until we unite, realising that we are not alone in the problems that we face (as our alienating work environments may have us believe) then it is going to be impossible for us to continue to rise.

I grew up in predominantly white spaces and it was not until my later years that I established close circles of black friends, who had faced similar experiences to mine. Being able to discuss and make sense of the experiences that I have faced has been vital to my becoming a more balanced, happy young woman. Increasingly, I’ve been attending events that are “safe spaces” where we can discuss oppression openly, without fear of judgement. I honestly feel that as your circle of sisters grows, so does your confidence. I have a brilliant, diverse friendship group some are writers, academics, comedians and each one is expressing her #BlackGirlMagic how she sees fit. Surrounding myself with beautiful, positive role models allows me to move beyond all the other negativity.

It is vital that as we accomplish more within the black community that we share our opportunities with each other even if this simply means giving advice and does not extend to mentorship. If we do not continue to ‘lift as we rise’ and create strong circles of sisterhood then our workplaces will continue to be homogenous, suffocating environments. So when you next see a sister in need of some support then please do tell her that she is not alone, we have similar experiences and that she is still magic but we are all real.