One of my most embarrassing memories from secondary school involves a dried piece of pork called bak kwa. My mum, who’s originally from Singapore and moved to this country when she married my British dad, used to bring slices back for us when she visited. One day I made the mistake of taking some bak kwa to school for my twin sister. One of her classmates saw the freezer bag of reddish-brown meat before I could secretly put it in her locker and said something like, “eurgh, what is that?” A sense of regret and shame started to crawl over me. I stuck to safe snacks for the rest of my school days – Twirls and lots of toast.

This floated back to me during an episode of Ugly Delicious, the Netflix documentary series by Korean-American chef David Chang, about fried rice. Chang convenes a round table of Chinese food obsessives to discuss the “giant, 1000-pound gorilla in the room”: racism towards Chinese food. They start by talking about how mainland Chinese food has mutated into American-Chinese food. Chang administers a simple test to tell the difference between the two: “Will white people eat this?”

“The country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres and yet the food of its entire population tends to be lumped under the amorphous umbrella of ‘Chinese'”

This bastardisation of Chinese food to suit Western tastes is just as visible in the UK. Think of the dishes that crop up on Chinese menus like sweet and sour pork and chicken chow mein. I ask Ally Tan, a Singaporean lawyer who moved to the UK in 2011, how she thinks Chinese food is perceived in this country. “I’m not sure that most people are aware that there is more to Chinese food than Chinese takeout,” she says. “It’s seen as ‘drunk’ food or a guilty pleasure – something you eat when you’re too lazy to cook and want something greasy and sinful.” Of course, a lot of white people don’t think like this. Tan emphasises that the friends she has now are interested in learning about her culture and my sister and I often host Chinese New Year parties for our school friends.

Another problem with Anglicised Chinese dishes is that it perpetuates the legacy of ignorance when it comes to appreciating China’s regional cuisines. The country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres and yet the food of its entire population tends to be lumped under the amorphous umbrella of “Chinese” by Westerners. “There is definitely a lack of understanding about how varied Chinese food is and how many different styles of cooking there are,” Tan says. “Spicy Sichuan dishes are nothing like fresh, steamed Cantonese dishes for example. I think this is a reflection of the lack of understanding of how diverse and varied Chinese culture is itself, and how it can differ between China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore etc.”

“European foods are considered refined, accomplished and worthy of distinction”

In Ugly Delicious, Alan Yang, the Taiwanese creator of Master of None, marvels at the fact that you now find regional Italian restaurants in big cities. In 20 years, he asks, will it be the same for Chinese food? Serena Dai, the editor of EaterNY, remains unconvinced. “Italians are white,” she says. Regional Italian food has been allowed to flourish because European foods are considered refined, accomplished and worthy of distinction. Whereas Asian food, and especially Chinese food, according to an article she wrote on EaterNY under the headline, “Please stop writing racist restaurant reviews,” is often perceived as “dirty, strange and unhealthy”.

The Guardian ran a story in March with the headline, “Some Chinese ready meals found to have more salt than 11 bags of crisps.” The Dumpling Shack Instagram account snapshotted the article and commented. “I just don’t understand the need to single out and demonise Chinese takeaway-style food. I don’t think anyone in the world would claim it’s a healthy option much like the majority of fast foods. Why is Chinese takeaway food being singled out?” I conducted a very unscientific experiment on a supermarket’s website where I compared the nutritional information on 400g ready meals – chicken chow mein, beef lasagne, classic fish pie and macaroni cheese. Highest in salt was the chicken chow mein with 3.8g, but also in the red range were macaroni cheese (2.3g) and the beef lasagne (2.1g). All contained additives.

MSG often gets bandied around in the same breath as Chinese takeaways. Dr Lucy Chambers, a senior scientist at the British Nutrition Foundation, explains. “Glutamate is naturally found in many foods such as meat, fish, poultry, cheese and milk (including breast milk), soya sauce, tomatoes, mushrooms and other vegetables, and gives food an umami (savoury) taste. The manufactured form of glutamate, monosodium glutamate (MSG), is added as a flavour-enhancer to many processed savoury foods including snack foods, spice mixes, sauces, soups and ready-to-eat meals,” she says. What this means is that MSG pops up in a lot more foods than just Chinese takeaways. As Chang puts it, “No one ever says, ‘Doritos made me sick’. But look on the packet. There’s MSG.”

“I can’t speak Hokkien, my grandmother’s dialect, so food has become our language. The only words my sister and I know how to pronounce properly are hó-chia̍h, ‘tastes good'”

There definitely wasn’t any Maggi Liquid Seasoning in my mum’s store cupboard. Now when friends stop by my parents’ house for dinner, there will be a Chinese feast waiting on the dining table. Back when my sister and I had sleepovers, it was my mum’s fluffy pancake stacks that got rave reviews. Eating Chinese food was like having my Chinese middle name “Enmin” printed at the top of my timetable. It was a reminder that I wasn’t white.

I also feel a little like the outsider when I visit Singapore, but this time because of my partial whiteness. It’s when I’m sitting in a restaurant and tentatively turning the Lazy Susan to stall time because I don’t recognise the dishes set in front of me that I remember: Chinese food can be both dazzling and daunting for me. I’m also humbled by the memory of my sister and I having a deep-seated fear of wontons because of their slimy texture and holding our noses in the “smelly” wet market. I hope I’ve learnt to not look at food with fear or disgust just because it’s alien to me.

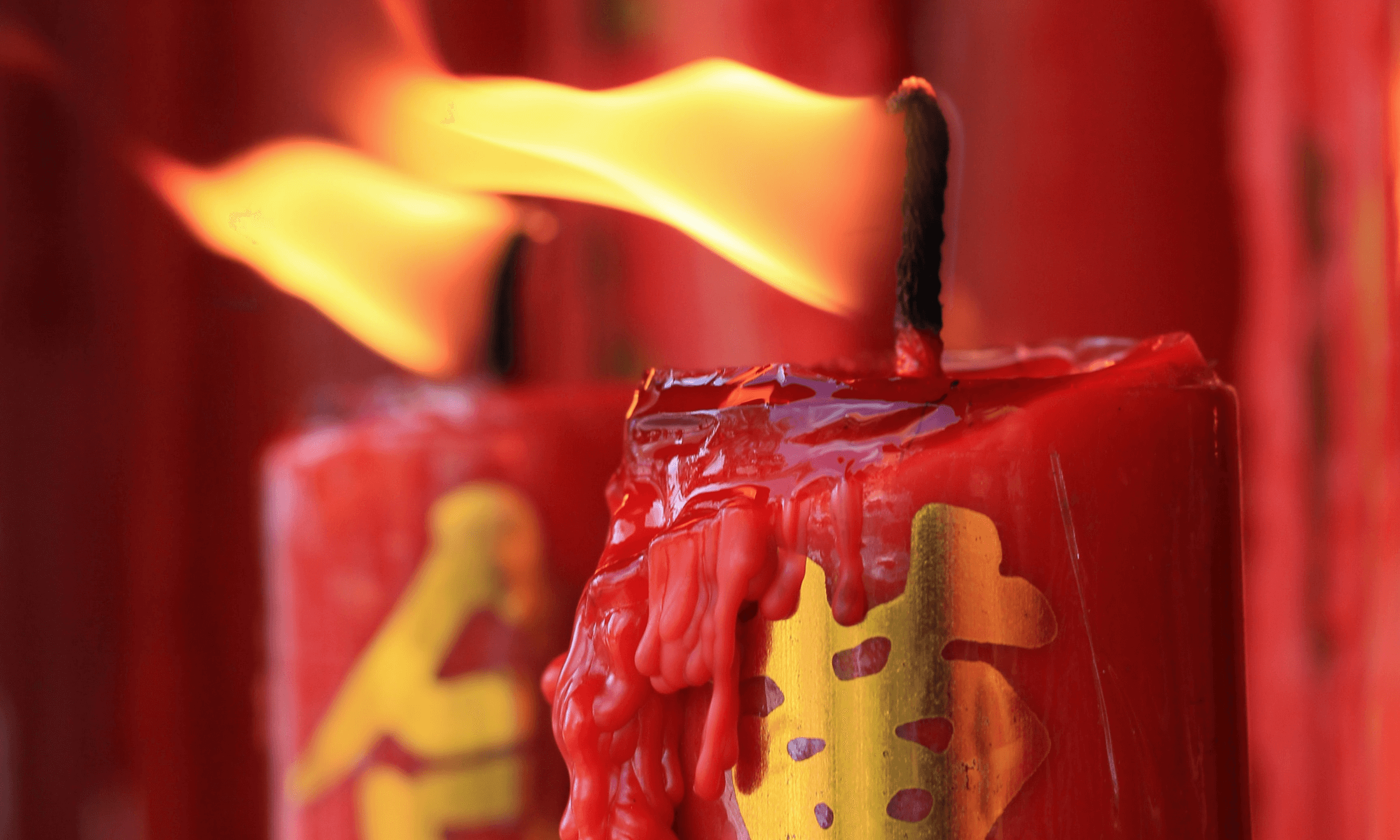

Food really is the lifeblood of Chinese culture. My Singaporean relatives tell me, “you’ve gained weight” like it’s a good thing – I’ve obviously been eating well. I can’t speak Hokkien, my grandmother’s dialect, so food has become our language. The only words my sister and I know how to pronounce properly are hó-chia̍h, “tastes good,” so we can lavish praise on her chicken curry and popiah. Tan found herself slowly gravitating towards the Singaporean and Malaysian community at university because of their relationship with food.

“How often have you heard someone say they got sick from Mexican or Indian food compared with French or Italian?”

They missed what they ate at home and wanted to cook communal dishes like hot pot together. “The result,” she says, “was that I became more separated from my non-Singaporean peers at uni. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to engage with my white peers, it was that given a choice I would rather eat Asian food than Western food. It was also difficult to get white people to eat Asian food – especially in a big group, the safest thing was to always default to white people food.” The issue of choice is an important one. A white person can eat Western food and a Chinese person Chinese food, but neither should judge what the other has chosen.

Unfortunately, Chinese food isn’t the only cuisine that gets pilloried in the Western world. How often have you heard someone say they got sick from Mexican or Indian food compared with French or Italian? I don’t have the answer about how to stop racism towards Chinese food and the stereotyping of cuisines. A reminder, from parents and teachers, to always be accepting of other cultures, and more speciality restaurants outside of big cities would be a start. Restaurants like Poon’s – a pop-up run by Amy Poon and named after her father’s Chinese restaurant on Lisle Street, which opened in 1973 and served dishes like Zha Jian soup noodles – are proof that this country wants more than egg-fried rice, with its menu of dan dan noodles, claypot rice with wind-dried meats and Hakka pork belly. “One of my mother’s concerns about our menu,” she says, “was the lack of anything recognisable, but my belief was and is very much that people only want what they know. Unless we let them know more, they won’t know to want it.” What I know is that I’ll never pretend I don’t have a Chinese name or that I don’t like dried meats again. My children will be fed on the food of their ancestors and will have better palates for it.