The first time I realised I wasn’t just black, but very black – blue-black, berry-black, midnight-black – I was on a school excursion to Canberra and someone confused me for a black marble sculpture of a dead coloniser. At first I was worried she’d had a heart attack but then my concern about looking like a dead white coloniser took over.

I’ve learned to sit very still in public, and limit my movements to make people comfortable and unafraid, but even then the fact that I can’t count how often I’ve been confused for a sculpture, even in the middle of a supermarket, means that people aren’t expecting a thing as black as me to be real and human.

“I can’t count how often I’ve been confused for a sculpture, even in the middle of a supermarket, [meaning] that people aren’t expecting a thing as black as me to be real and human.”

In the predominantly white scenes that I navigate as an artist and a young person in metropolitan Australia, my skin is fetishised in really blatant ways. Proximity to me and my skin is desirable in these vaguely and sometimes overtly politically aware scenes, and my skin itself, coupled with my gender and sexuality, is highly politicised. To be close to me in any way for non-black people who seek social capital, is to be seen as a “good ally”.

The very black body is often seen as a tool for non-black and lighter-skinned black people to journey through their own desires and their own politics while remaining safe because they’re actions around intimacy and desirability are always enacted on to the very black body and never the other way around – they overcome their fear of the body, they date the body, they gain capital from their proximity to the body, they learn from interacting with the body. What that body gains or loses is irrelevant. To be close or intimate with a person like me is to have overcome social norms; you’re publicly proclaiming to see desirability in the dark-skinned black woman’s body.

“The very black body is often seen as a tool for non-black and lighter skinned black people to journey through their own desires and their own politics”

When I went back to South Sudan for the first time in over 20 years, people were surprised that I had maintained my skin colour. The lure of giving in is understandable, especially when you’re alone in your world as the single marble sculpture in a town full of “real” people. It’s a disservice to think of colourism as anything less than an act of white supremacy and global anti-blackness and it’s a disservice to think of colourism as purely based on aesthetic desires but, for the most part, the conversation stays shallow. When I talk about colourism in relation to bleaching, I’m told I’m jealous or taking beautification practices too seriously. My dark skin is used as a tool to silence my experiences of dehumanisation through colourism.

“It’s a disservice to think of colourism as anything less than an act of white supremacy and global anti-blackness”

In a heteronormative, predominantly Christian country like South Sudan – where many of our neighbouring countries have people with naturally lighter skin than us who are often denied access to their full African identity by being assumed mixed – being as dark as we are, for women especially, is a nuisance at best.

My family emphasises femininity in the ways that a society like ours expects it to manifest. My aunties say, “Your hair can be short but you have to wear jewellery and dresses to balance it. You don’t have to wear make-up but you have to be friendly and smiley to be more beautiful.”

As very dark women in a society that 1) demands a specific brand of femininity from us but 2) denies that to us because of our dark skin, we’re mocked for bastardising femininity that we aren’t allowed anyway but told to overcompensate for what we feel we’re missing.

Regardless of whether or not we desire femininity, we’re denied access to it and we’re ridiculed and denied access to sexual agency because of the masculinity (read, undesirability for women in heteronormative society) assigned to us. When we embrace femininity, we’re ridiculed for automatically failing at something denied us and, when we embrace masculinity, we’re ridiculed for playing into a role that we have no choice over.

My cousin bleached her skin when we were in high school. We were born the same shade but, over time, she became significantly lighter than me. She never wanted to be white – that’s very, very rarely the case when people bleach their skin – she just wanted to beautiful and desirable.

Over time, people began to assume she was African American and she liked that. Sometimes people assumed she was Ethiopian or Somali and she liked that, too. When people began assuming she was mixed European or Arab, she beamed. She never called me ugly, but she called me interesting and began to embrace the dehumanising language used by non-black and lighter-skinned people to refer to me. Interesting. Fascinating. For her, bleaching her skin wasn’t about being white, but about distancing herself from blackness and its associations as much as she could.

“For my cousin, bleaching her skin wasn’t about being white, but about distancing herself from blackness and its associations as much as she could.”

My cousin especially loved how she was received in relation to and in comparison to me. I was the litmus test for blackness as the very dark-skinned, big-lipped, flat-nosed, wooly-haired cousin; my blackness was and never will be questioned. But compared to me, her lighter skin distracted from her other unquestionably black features which distanced her from her inherently black blood and, although she was very clearly not white, what she gained was a closer proximity to whiteness and therefore access to femininity and desirability. Even if it was just a little bit, she was beautiful and desirable.

Darkness is associated with hypersexuality and an animalistic, uncontrollable nature. When that’s intersected with the hypermasculinity historically assigned to dark skin and the dehumanisation of black peoples, it creates an environment of aggressive misogyny towards dark-skinned black women. Women are valued on their desirability – desirability is equated with whiteness or close proximity to whiteness and heteronormative ideas of femininity – socially, then, there is no acceptable space for dark-skinned black women to occupy outside of service.

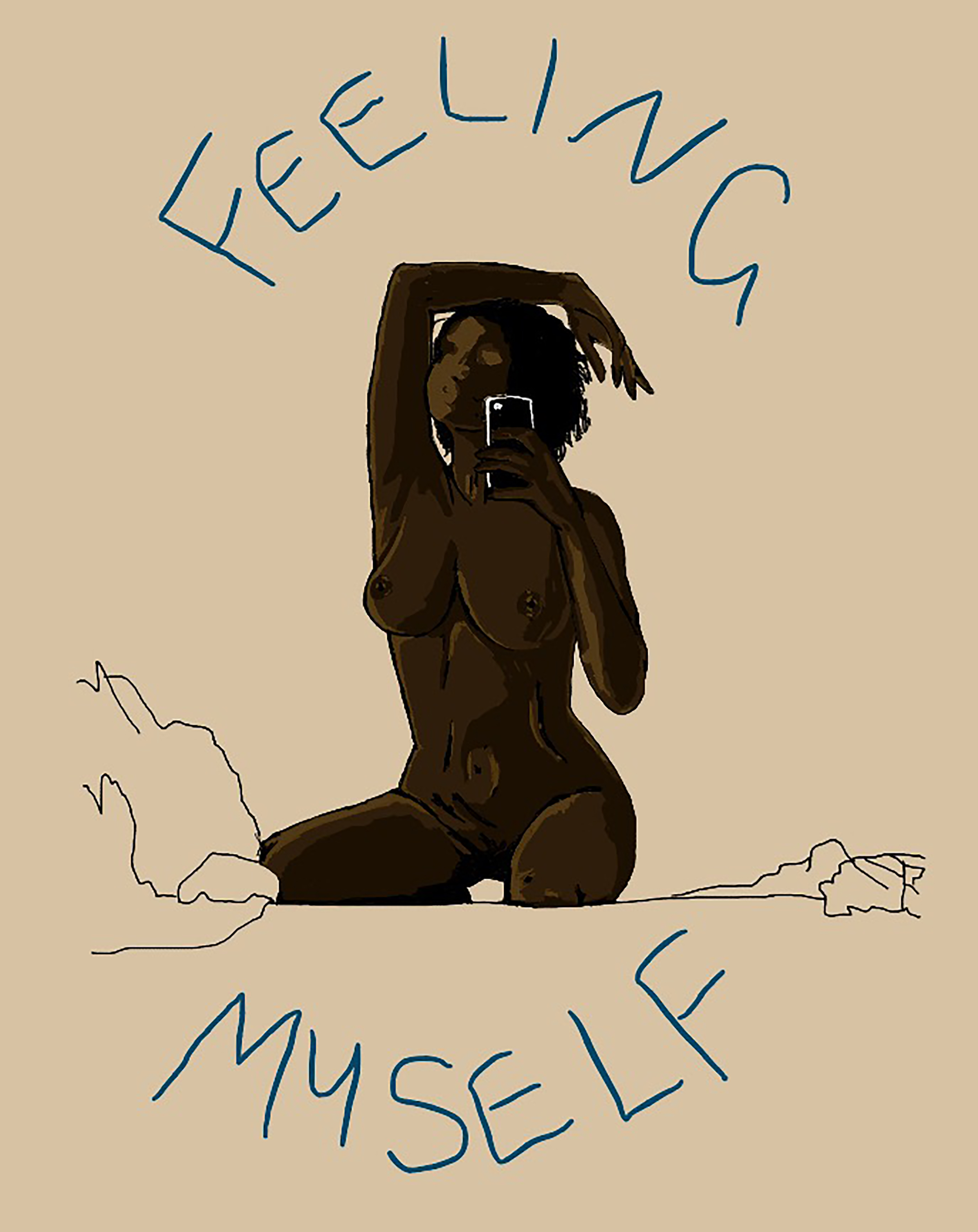

As dark-skinned black women in the diaspora, taking autonomous control over our politicised and dehumanised bodies is one of the most challenging and necessary things we can do. When we take ownership of our bodies and our sexualities and our images in really intentional ways, it challenges the limited roles we’ve been assigned in society.

“We must disrupt the dehumanisation of black bodies”

Whether we desire femininity or masculinity or a hypersexual image or strength or none of the things society assigns us, or all the things society assigns us, we disrupt the dehumanisation of black bodies. And to do that, non-black people and lighter-skinned black people have to become aware of the ways they contribute to the dehumanisation of dark-skinned black women and the ways their anti-blackness and misogynoir manifest.

Get involved with gal-dem’s skin lightening series. Comment, tweet us at @galdemzine using the hashtag #skinlighteningseries, or email info@gal-dem.com if you would like to share your experience.