Sitting awkwardly on a cheap wooden chair in front of my boss, my heart dropped into my stomach as he uttered the self-congratulatory “well you know I have plenty of black friends”.

Throughout the duration of my four week summer job, I painfully tried to bite my tongue as I encountered a wave of micro-aggressions and insensitivity from my boss. With the recent dismissal of safe spaces and “political correctness”, one would have thought that racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism and Islamophobia were tropes of the past, imagined and brought into the public sphere by whiny leftist liberals unable to cope with the challenges of the real world.

I do not deny that in some cases, terms such as “sexism” are cheaply thrown around, as accusatory rhetoric and name-calling serves as a replacement for intellectual and sustained debate. Certainly, our language for talking across difference has increasingly disintegrated, as those on the left are dubbed delusional socialists, meanwhile those on the right are labelled ignorant racists, with little rational middle ground in between.

This was bigotry disguised as a discussion by a man who was controlling my pay.

But this was not a debate. This was bigotry disguised as a discussion by a man who was controlling my pay. My boss’ comments included a lecture on how Africa’s problems were caused by lustful black women unable “to close their legs”, thus creating masses of poor pot-belled children. This simplistic yet avoidable problem could be solved by him, or another like-minded intellectual white male simply dropping a large number of condoms into the region. His comments reeked of the entitlement of a 19th century colonialist in the midst of the scramble for Africa, rather than a university-educated 25-year-old man. Far from recognising the dark history of colonialism juxtaposed with the awe-inspiring complexity of continental Africa, for him, Africa was a homogeneous dust-filled wasteland. Meanwhile unbeknown to me, he had “joked” scathingly about black men constantly stealing, whilst I had popped to the bathroom during our introductory meeting.

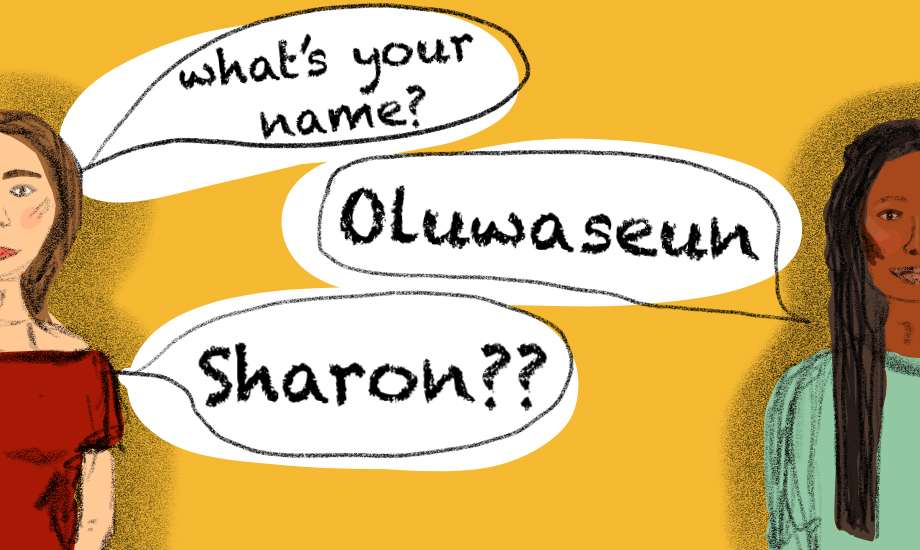

There was one occasion at dinner, whereby the moment my co-worker, who dared to possess a non-anglicised name, sat down, he simply asked her “what are you?” Upon hearing her response, he continued to question whether her father was a “stereotypical Polish plumber.” Although, he thought nothing of condescendingly spewing othering terms such as “black men” and “Poles”, I dwelled upon the countless European migrants who now, in our post-Brexit society, fear abuse on streets they regard as their home. My mind slipped to my privately educated 14-year-old brother, full of witty jokes and drive, who was viewed as a threatening thug by the white elderly couple who immediately locked their car doors upon his crossing their path. His only crime was existing within his own skin, skin which for some represents dangerous, uncivilised criminality.

But I wasn’t to worry as it was all “banter”.

I didn’t want to create tension. I didn’t want my complaint to act as justification for a reduction in my pay. I didn’t want to be a spokesperson for my entire race.

Looking back, it was not his words that left a hollowing sensation in the pit of my stomach; it was my inability to stand up to such behaviour within the workplace. I didn’t even formally lodge a complaint. In fact, it was my white co-worker who was so appalled by his rhetoric that she felt compelled to push the matter further in her appraisal and alluded to the fact that his comments had upset me as well as others within the team.

Whilst my co-worker intellectually understood notions of racism and could discuss it in a detached manner, as a black woman I am emotionally, politically and intellectually entangled within issues of race. I have watched my friends and family experience institutional racism, internalised bias and cultural appropriation within schools, in relationships and in their day-to-day lives. For all of my impassioned discussions at university, retweets and articles, when actually confronted with prejudice, I simply didn’t want to make a fuss. I didn’t want to create tension. I didn’t want my complaint to act as justification for a reduction in my pay. I didn’t want to be a spokesperson for my entire race. I didn’t know how to be. How do I begin to explain racism in a coherent, unemotional and non-threatening manner to someone who so confidently expressed his prejudices?

I respected my boss’ abilities to organise and lead the team yet was appalled by his ignorance.

I was in a privileged position; my job was a temporary summer role, absorbing four weeks of my enviably four-month long vacation. Ultimately, it was merely a job that I took not out of necessity to raise a family or to eat, but to fund my unpaid internships and university balls. I respected my boss’ abilities to organise and lead the team yet was appalled by his ignorance. When his comments were brought up in my final assessment, I calmly explained how his behaviour had made me feel and to his credit, he gave a somewhat defensive, somewhat sincere apology, explaining how he did in fact have black friends but wasn’t aware of issues such as cultural appropriation and was willing to learn more. We closed on friendly terms and I was encouraged by how receptive he was to my ideas and opinions, when I had the courage to actually voice them. I had the slight suspicion, however, that if in the future he is ever accused of spewing racist rhetoric again, I’ll be the “black friend” he refers to, in order to justify his bigotry.

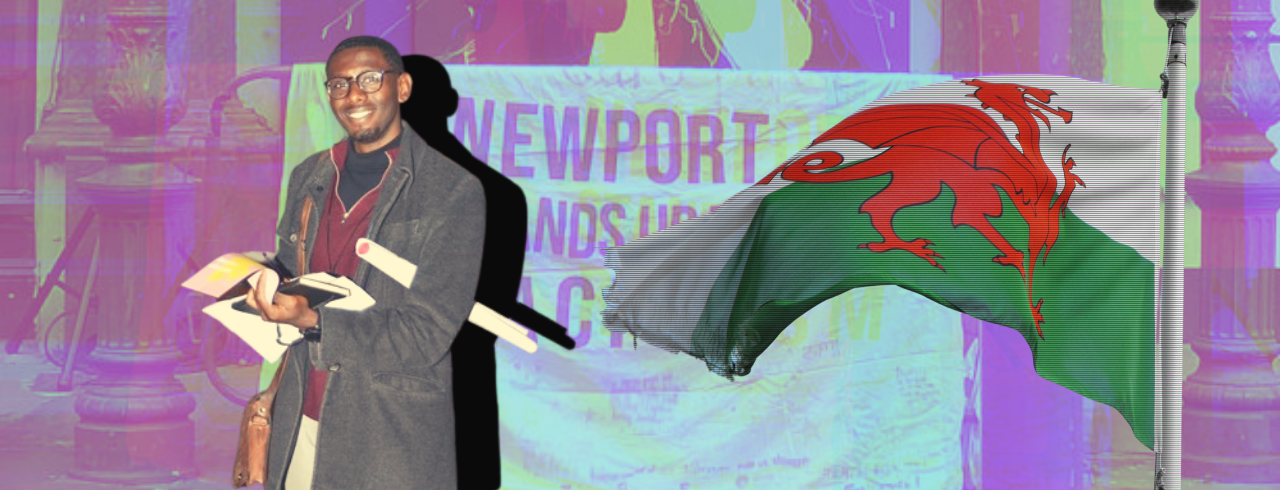

Overall, it was an exhausting experience. I believed and continue to believe that silence constitutes compliance in the face of prejudice. As a result, I felt like a fraud and was left questioning my identity and ability to fight for equality when it really mattered. The summer job was not relevant to my future career as a journalist and it made me question whether I would have the confidence to challenge those same remarks if they were made in a television studio or at the desks of a local newspaper.

Throughout my life, I have attempted to be all things to all people; the bubbly and amicable friend and co-worker, unwilling to create tension and wanting to be liked by all, alongside the articulate picket holding activist desperately pushing for equality. Now, in my final year of university, as I hurriedly apply for internships and jobs, I am fully aware that aligning the two versions of myself will be a conflict that I will have to endure for the entirety of my working career.