“All we did was flee our own countries because of problems, but they don’t treat us like human beings at all.”

Many women who are seeking asylum in the UK are survivors of rape or other gender-based violence. These women experience high levels of distress, which is compounded by being detained indefinitely and forced to talk about traumatic struggles as evidence for their asylum cases, with very little support.

In the absence of proactive detention policy reform from those who are well-salaried to design it, UK-based charity Women for Refugee Women have set out to perform the task themselves. Their recommendations are detailed in a report- The Way Ahead: An Asylum System Without Detention– published today. Their end product: a proposed asylum process which is centred around providing support and engagement to individuals, in order to resolve cases more easily and reduce the use of detention until it is completely dissolved.

Every year, 2,000 women are locked up in immigration detention. Yarl’s Wood Immigration Removal Centre (IRC), where the majority of asylum-seeking women are held, denies women both their privacy and their dignity while in detention. The Way Ahead describes how women are routinely watched by male guards while in bed, using the toilet, taking a shower and getting dressed. Research has proven that being locked up is a distress trigger for many women who have had similar experiences of incarceration, in some cases “unlawfully”, in their countries of origin.

The UK is the only country in Europe to practice immigration detention without a time limit. The UK government claims that detention centres are crucial in aiding them in removing people from the UK, and yet 84% of women who were detained in 2015 were eventually released back into the community. It costs £35,000 a year to detain one person, and the expense of running the centres totals £125 million. Reformed policies to prevent detention of pregnant women and families with children have been agreed upon but not yet implemented.

In recent years, governments have sought opinions from “service users” or “experts by experience” in areas such as mental health support, drug and alcohol treatment and the criminal justice system. When it comes to reforming immigration detention, both the government and the Home Office should be listening to those who have been or are going through the UK asylum seeking process.

Women for Refugee Women convened four workshops involving 33 women at different stages of their asylum-seeking process in London, Birmingham and Manchester. In the workshops, women spoke of the Home Office’s “culture of disbelief.” A culture they described as racist, discriminatory and with decision makers actively looking to reject their claims. During their main asylum interview, many felt that they were aggressively questioned. They described being asked the same questions repeatedly as well as being asked to produce evidence they couldn’t possibly get hold of. One of them went on to say that in the UK: “Until you’re British, you are not yet somebody.”

Outside of detention, temporary housing provided by the Home Office to people seeking asylum is often of a very poor condition, and is highly overcrowded with women reporting that male housing officers come and go as they please, restricting their right to privacy. The Home Office gives people seeking asylum around £5 a day (about half of a jobseekers allowance) to cover their basic living needs including public transport and phone credit- quickly depleted when making phone calls to solicitors working on their asylum cases. Those undergoing the asylum-seeking process are not granted the right to work, and women felt that this has a major impact on their self-esteem.

The whole asylum process causes a decline in mental well-being, and the impact of waiting, whether it is for the date of their main interview or for a decision on their claim, was particularly distressing. One woman said: “I can’t plan, I can’t say to anyone what I’ve been doing in this period apart from waiting for an asylum claim.”

In the workshops, some women talked about the trauma of being locked up, including attempted suicides. To those who had not been detained, the possibility of detention was frightening. A woman said: “They used to give me documents all the time, or the letters they used to send me said ‘you are liable to be detained.’ Even when I was having my interview, the only thing I was worried about was detention.”

Most asylum-seeking women interviewed had experienced traumas such as rape, forced marriage, domestic violence and being trafficked for prostitution. In addition, women had been forced to physically and emotionally leave behind everything and everyone that they knew to seek asylum in a foreign country. From this position of extreme vulnerability, women are expected, unassisted, to work their way through the incredibly complicated asylum system, for the most part not receiving any updates or information about what decisions have been made.

Although many women experienced (or were experiencing) high levels of uncertainty and distress from the lack of information and updates they received from their solicitors, some women were very positive about their legal representation. Women spoke most of the vital support they receive from friends, people they had met in the UK, solicitors, charities and peer support groups. Especially when asylum claims were refused and their accommodation and financial support was terminated, charities were particularly important.

“I would not say the UK has a bad asylum system, but they don’t support people emotionally.”

In The Way Ahead, Women for Refugee Women propose a structure of support for those going through the immigration system using case managers. By building a relationship based on trust, case management is a person-centred approach which promotes the individual’s health and wellbeing for a more efficient asylum seeking process. Case managers would work with an asylum seeker to understand the process they are going through as someone separate from the system. Women who have experienced violence are commonly more comfortable sharing their experience with female key workers-through this system case managers can ensure that all available and relevant evidence can be submitted to decision-makers at the home office. This not only promotes good decision making but also timely and effective case resolution.

Countries such as Sweden (which detained 3,500 people in 2015, whilst the UK detained 32,000 people) who have adopted an asylum system based on support and engagement, aim to resolve cases, even when they have been refused, within communities, without the use of detention.

When this model was presented to the women in the workshop, they were particularly interested in the emotional support case managers would offer. To them, although a system like Sweden’s which uses detention more sparingly was good, it was not good enough. They emphasised the need for asylum systems without any detention at all.

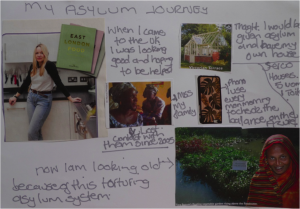

All the artwork featured in this article is anonymous, made by women who attended workshops at Women for Refugee Women.

Women for Refugee Women is a London based charity supporting and empowering women who are going through the asylum process in the UK. They work to tell these women’s stories in the media as well as publishing research to inform politicians of ways to make the asylum system fairer. With the help of the London Refugee Forum, Women Asylum Seekers Together London, Hope Projects in Birmingham and Women Asylum Seekers Together Manchester, their newest report: The Way Ahead: An asylum system without detention has been published. It launches today at the National Refugee Women’s Conference.

This piece is part of gal-dem‘s #ShutThemDown series, exploring the UK’s immigration detention estate which indefinitely incarcerates over 30,000 people a year. A disproportionate percentage of the UK’s detention population are working class people of colour, and asylum seekers.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?