“Gosh, abuse of women is so bad in India/Somalia/Yemen/Saudi Arabia/*insert generic brown nation* – isn’t life awful for them?”

This is the common response I get when I tell people that I work in ending violence against women and girls. It doesn’t matter that I then go on to explain that, actually no, I work in London, England, United Kingdom, you know – the global north. For some reason, the fixed idea is still very much that it is scary men of colour who abuse poor, oppressed women of colour. I’ve worked in this field for a number of years, and the response has virtually always been the same – that the situation is so bad “over there,” and when it does happen here it is awful South Asian men abusing white girls because of their inferior culture/religion/race. It seems there is a real resistance to accepting the universal nature of violence against women.

Now of course I know that violence against women and girls (VAWG) happens in the global south. Many studies show that the 10 worst places in the world to be a woman are mostly, if not exclusively, in Asian and African countries. What is less widely known is that in the UK, at some point in their lifetime, one in three women will experience sexual abuse, one in four will experience domestic abuse, and in a week, 1,000 women are raped and two are murdered by a current or ex-partner. This happens to women who are CEO’s, students, stay at home mums, and anyone in between, regardless of race, class, religion, age and sexuality.

So why are we only quick to see the fault in certain communities? And what is this fascination with the global brown victim? Women of colour and women from the global south seem to be awarded some form of exclusivity of suffering and with this emphasis, we increasingly find women of colour being seen in need of “saving”.

“I’ve come to realise that our understanding of violence against women and girls is increasingly being viewed through a racialised and even neo-imperialist lens.”

Indeed, we’ve seen this play out numerous times. The controversial activist group, Femen, whose tactics involved demonstrating topless in protest of the Muslim Hijab, showed us how much they cared about “saving” Muslim women by telling them how they are oppressed, without hearing from Muslim women themselves on the issue. We’ve even seen far-right groups like the English Defence League suddenly be interested in campaigning to end female genital mutilation. It’s difficult to believe that the motivations behind these actions are purely altruistic. Instead, I’ve come to realise that our understanding of violence against women and girls is increasingly being viewed through a racialised and even neo-imperialist lens.

What we see happening is the creation of a hierarchy of suffering that sees violence against women being a result of “inferior” cultures, traditions and religions, rather than a result of the universal concepts of sexism, power, and control. It also encourages a white saviour complex that creates a discourse where the Hijab is seen as a form of oppression, without a wider conversation about the ways in which all women’s bodies are policed. It leads to (rightly) a tough stance on female genital mutilation, but relative silence on the increasing number of labiaplasty surgeries. It leads to forced marriage being seen as a South Asian problem that doesn’t include shot gun weddings or mail order brides in its definition. It leads to the UK government criminalising forced marriage before making domestic abuse a crime in and of itself.

This othering of VAWG is problematic, not just for women of colour but for all women who experience gender based violence, as it denies a voice to those who have experienced it. By failing to see VAWG as the result of the misuse of power and control, and instead focusing on race and culture as the root issue, nations in the global north feel justified in adopting a “civilised the uncivilised” approach to others, whilst simultaneously feeling they have a get out clause in dealing with the issue at home. For example, under this Tory government, 24 refuges for women have closed and two in three women who approach refuges for help are now being turned away. This is happening whilst aid is given to nations in the global south depending on what they are doing to address gender inequality.

“These men, we were told, were predators because of their South Asian culture. Not because they were operating in a world where men are entitled to female bodies; not because they preyed on vulnerable girls, who the state had abandoned; not because they felt justified to abuse children in a society where young girls are sexualised and labelled as predators instead of victims“

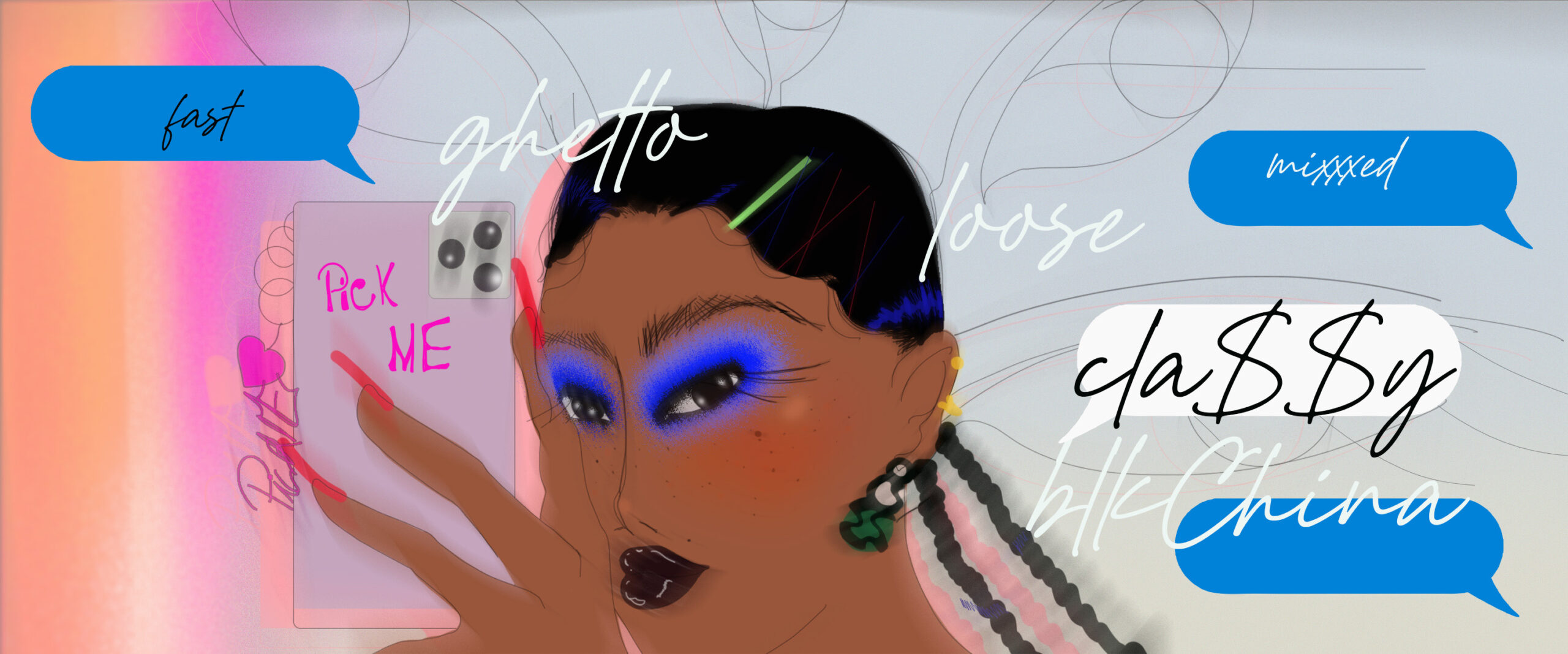

We also see this attitude lead to a perceived idea of who a perpetrator is. As not only do brown women need saving – but brown men need to be stopped. The coverage of the Rochdale child grooming case firmly placed abuse in the context of the heritage of the perpetrators. These men, we were told, were predators because of their South Asian culture. Not because they were operating in a world where men are entitled to female bodies; not because they preyed on vulnerable girls, who the state had abandoned; not because they felt justified to abuse children in a society where young girls are sexualised and labelled as predators instead of victims by judges. But because of their race.

Of course the same principle is not applied to white men who travel to the Far East to sexually abuse brown children. Nor does it apply to the newly elected president of the free world. That’s different. These cases are just locker room banter. You know, boys will be boys.

VAWG is being allowed to continue because it is not being addressed in a wider context of power and control. At my work, I raise awareness of VAWG through training, meetings and events – to a wide range of audiences. What I have consistently found is that it is much easier to adopt a narrative that says race and culture is at fault, because then we do not have to address more complex issues around power, control and gender inequality. We don’t need to put our society under a microscope and look at how we are complicit in the abuse of women through our victim blaming culture, our rape culture, and our patriarchal culture. Instead, we can dictate to others what is and isn’t appropriate behaviour.

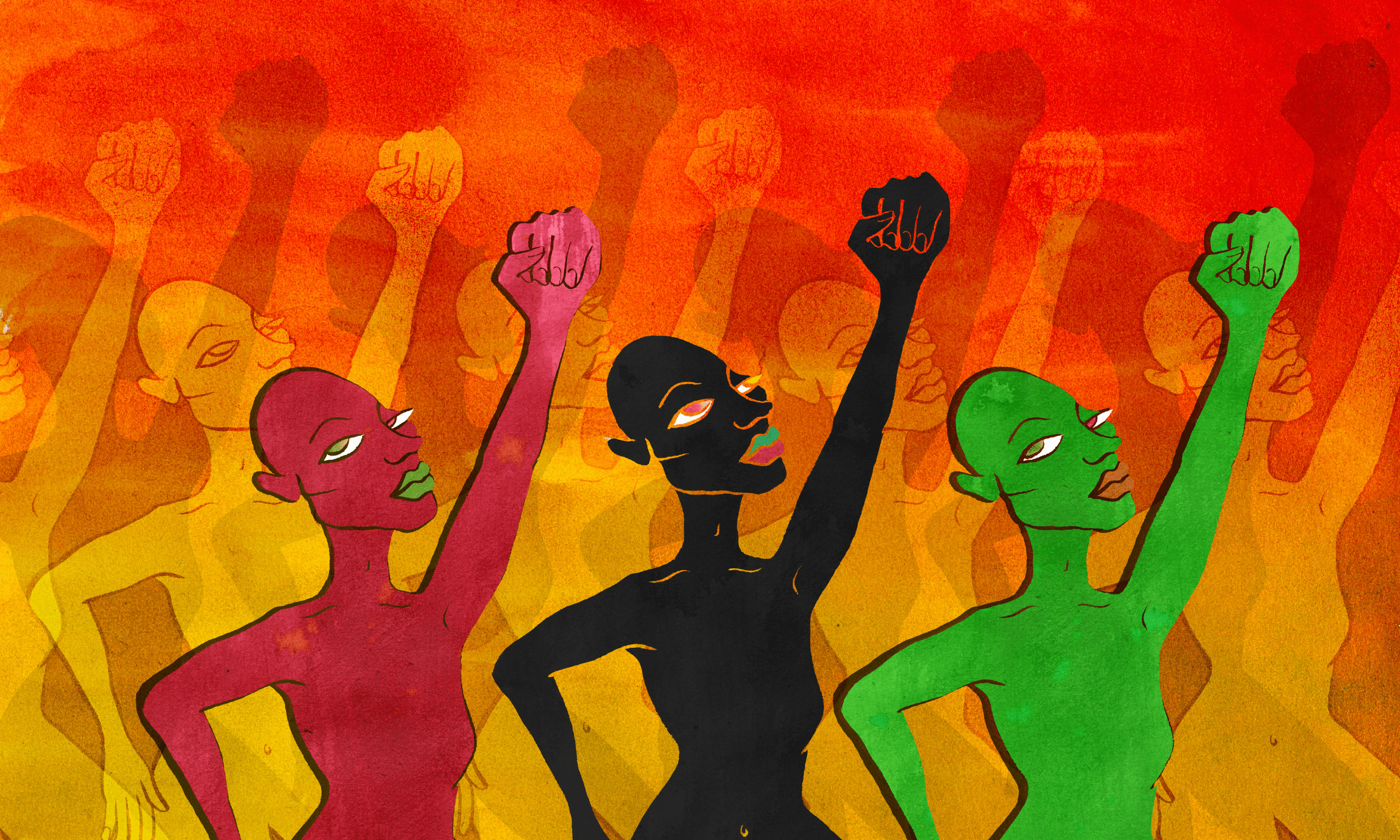

So what needs to happen? Well firstly, we need to change this narrative. Rather than being seen as silent minorities that need saving, the voices of women of colour need to be included in the discourse in shaping support services. A two way approach is needed where the global north and south share best practice and inform each other’s work, rather than one telling the other how far they have to go. We need to recognise that we are all part of the problem, but also part of the solution.

It goes without saying that violence against women and girls is a global problem of epidemic proportions, where the biggest risk to 51% of the population starts with the words “it’s a girl.” This can only change if we tackle the issue in all our communities head on – not hide behind an us versus them narrative that only serves to fail all women.