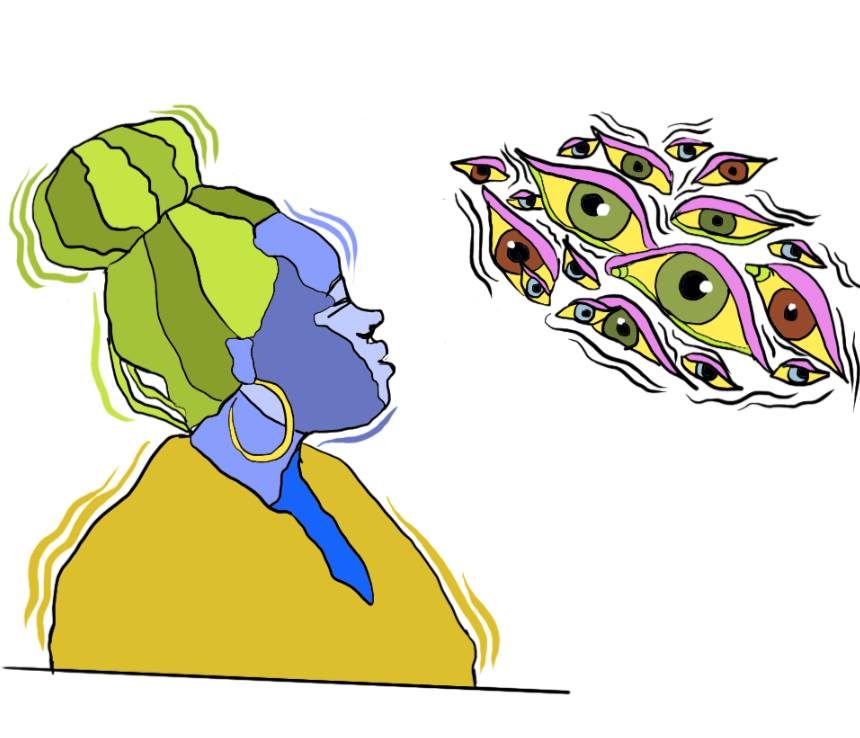

The term “queer” can be defined as “an umbrella term representative of the vast matrix of identities outside of the gender normative and heterosexual or monogamous majority.” However, even within this community which seeks to be as inclusive as possible, the spotlight tends to fall on some over others, particularly those who are white, male and/or cis.

Queer women and non-binary people of colour, often existing on the periphery of the queer community, face a separate struggle, one referred to by comedian Wanda Sykes as a “trifecta of discrimination”: being a minority, queer, and a woman or femme-identifying/presenting person. These issues don’t always receive the representation they deserve on the larger LGBTQIA+ platform. Highlighting the importance of making our own and form our own networks, such as the South London-based art exhibition BBZ. It’s through these means that we’re able to mould our own narratives.

This week, I spoke to a number of people of colour, all identifying in some way as queer or simply “not straight” or “not cis”, who shared their varying experiences of queerness and the roles race and culture have played in further layering their identities. Quotes have been presented anonymously.

Acknowledgement

“I think the possibility of my not being straight has been around in my head for about 3 years. However, until August 2015 I was in a monogamous heterosexual relationship, so when I talked about being bi it was often invalidated by others so I kept fairly quiet.”

“Probably didn’t acknowledge anything until I was 18, even though my attraction for women and femme-bodied people existed long before (maybe since I watched Christina [Aguilera’s] Dirrty video aged 8). I had really low self esteem and got a lot of my validation from men and it took me growing more confident to really come to terms with my bisexuality/queerness.”

“It’s honestly been a very recent discovery of mine. I think I had an inkling in October (2015) and maybe even before that but I think it was only around January this year that I acknowledged the real possibility and about March when I sort of found a loose label.”

“I’ve acknowledged I’m gay from as early as I can remember, at 7 or 8. I came to terms with it properly at 16.”

“I first had flutterings of crushes on girls when I was 12, but I remember not understanding what I felt, or ever having heard of any other brown person feeling what I felt, so I squashed my feelings for many years. By the time I was 16, I was fully in love with one woman. I still was in complete denial though. I didn’t know how to acknowledge any of the clues that made it so clear that I was queer (in terms of sexuality) because I didn’t know I was allowed to. With time, I’ve realised that there is never one moment of ‘realising’ my sexuality or gender identity, it’s always changing as I am. That’s been very hard to accept As for my gender, I’m still in the process of acknowledging that I am not cis, and that process involves learning about how colonialism imposed the gender binary on PoC around the world, how gender roles are largely determined by race and about my own cultures and religions (Indian Hindu) history of celebrating and revering trans and gender non-conforming (gnc) people and deities.”

Coming out

“All of my friends and immediate family know about my sexuality, as does most of my extended family. It was easy to come out, as I didn’t so much come out but let people figure it out for themselves. I don’t agree with the concept of coming out. Why do people need to suddenly be made aware if my sexual preference differs from the majority? It’s not something I would expect anyone to tell me because it’s none of my business.”

“I find coming out usually easy, because I’m confident in my queerness. I get a few surprised reactions and intrusive questions sometimes , which I blame on heteronormativity for. People who think they are very liberal because they’re not against gay marriage still have a lot of heteronormative expectations which they are reluctant to admit.”

“When I was still with my (now ex) partner, I remember talking about women I found attractive and having straight male friends tell me I wasn’t allowed to say whether women were attractive or not. And then also effectively asking me to ‘prove’ my sexuality to them sufficiently –which I never could because to them that meant having slept with other women and my boyfriend was the only person I’d slept with at that point. I guess I came out to my parents by telling them, over the phone, that I was dating a woman. My mum’s response was ‘Oh, are you bi then too?’ (my sister came out a year before me) and I’ve heard nothing of it since. Though, to be honest, I think my mum’s just given up trying to keep up with my love life/lives!”

“My coming out to my friends was barely a coming out. I just kinda told them and it was nothing, like, no big moment of cathartic release or any kind of beautiful running into the sunlight with rainbow tears of pride streaming down my face. So, that was fine.”

“When I was 18, I told a girl I went to school with who was already out. That was reassuring. Then I got pretty drunk at uni one night and decided to tell my close flatmates. Alcohol definitely helped, they were all really lovely about it. It has gone a similar way since then.”

Intersection with race and ethnicity

“Coming out to my parents is an impossibility. They are super liberal and accepting but they’re still Middle Eastern. Obviously not to say that all Middle Eastern parents are a type of way, but I know for a fact that it would never be resolved, and it wouldn’t be like those white-centric ‘it gets better’ campaigns because it wouldn’t; it would always be used in an argument against me or to shame my parents from other members of the family. I feel like the weight of it is doubled in a way, because if I ultimately chose to be with a girl not only could I never bring her home to my family, but they would also be forever gutted at the fact that they would be bereft of any grandchildren or a big marriage. I’m trying to come to terms with it because I’ve spent so long atomising and packaging parts of myself to suit different people and different family members that I’ve had to look at this big shattered pile of glass and try and piece all the bits back together again, expecting cuts in the process, but finally having something be the way I want it to be.”

“Pride and the mainstream LGBT+ community is very white and growing up it was isolating to think that I couldn’t really be accepted within my culture or within the “safe space” of the LGBT+ community.”

“Being black, non-binary and not heterosexual has been challenging. I’m always accused of lying, being threatened or having people feel it’s okay to demonise me in some way. I’ve never put too much stock in the words of people outside of my community but the most harsh and vicious homophobia I have found has been from other black people.”

“Culturally and religiously, I’ve grown up trying to avoid sexuality in terms of acknowledging attraction at all, which affects my ability to recognise my sexuality. I’ve been encouraged to be modest and, although the hijab is about more than modesty, has kind of ended up desexualising me which affects my ability to recognise any sexuality within me.”

Final thoughts

“All of this is fluid. You are how you feel. It is nobody else’s role to tell you how you can and can’t identify. What you feel is real. Yes, it may change, but that doesn’t make any current, past or future experience invalid. Try and surround yourself with people who support you and validate you.”

“Do what suits you and you only; if you feel the need to come out, then absolutely do so, but coming out is not possible/the best decision for everyone – protect yourself.”

“Search for some form of support for what you’re going through. Whether that’s through queer friends or online communities i.e. Tumblr, it’s important to not feel alone. There are plenty of QPOC communities online and they’re usually quite accepting and affirming.”

“Unfortunately, I’ve found quite often that the only common ground I have with members of my family is that we share blood. Find people who will accept and love you and bring them in to your fold, because they will have a far more positive impact on your future than people you share DNA with.”

“I understand that displaying your sexuality may be difficult in front of people who haven’t had a pre-warning, but remember to question why you even have to discuss your sexual preference with people you aren’t sleeping with.”