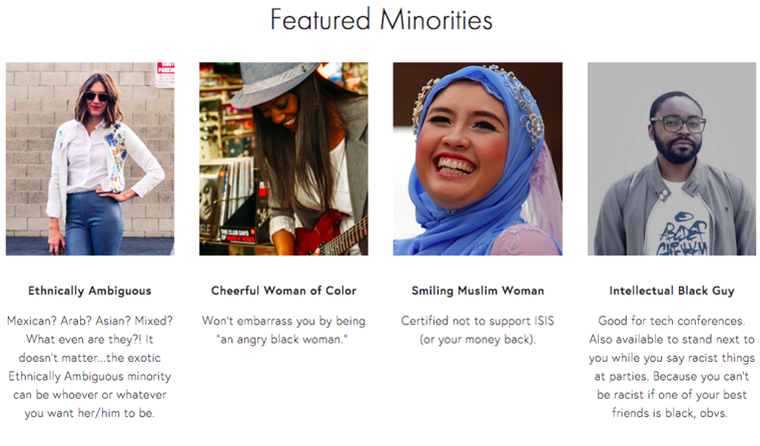

The proliferation of conversations surrounding the various injustices that different groups of marginalised people have to face has put white people, and white men in particular, in a tizzy of late.

Motivated by an imaginary tilt in the power scale, those in the best positions to receive more opportunities than historically oppressed groups ever have, have resolved to take a stance against the perceived demonisation of the “pale male and stale” (PMS) at the hands of over-sensitive lefties, and those who sympathise with causes championed by supposedly embittered groups like immigrants who refuse to “assimilate”, or women – particularly the black, brown, trans and feminist ones – who won’t shut up about the gender pay gap, racism, and literally being assaulted for existing.

Described last week as the “last group it’s okay to vilify” in his most recent column for the Guardian, Simon Jenkins has become the latest in a long line of white, middle-class, privately educated men, who have resolved to stand up for the right to avoid reminders about the privileges they routinely enjoy.

In a string of stunningly obtuse comments on Talk Radio following the publication of his article, Jenkins claimed that as an older, white man, he now knows what “it must have been like to be a black person 20 or 30 years ago” as well as suggesting that black women “just slide into” high-powered positions.

Aside from the fact that Jenkins seems to think that the fight against institutionalised racism ended decades ago, as a black woman who has worked in more minimum wage roles than not, who could not have completed my master’s degree in Newspaper Journalism had it not been for my NUJ George Viner Scholarship, who could not have taken on as much unpaid work during that time had it not been for my part-time job as a receptionist, and who generally understands the economic and social barriers that make it difficult for black women to succeed in all walks of life – I know that the “black women took my job” argument does not stand. Statistics also confirm this. Black graduates have the lowest rates of employment or further study after they finish their degrees.

“Jenkins flits between a shallow understanding of the fact that discrimination against othered people exists, and what he sees as unwarranted and insensitive bashing of global white dominance”

Jenkins and other staunch opposers of “identity politics” (otherwise known as daring to acknowledge the legitimacy of the varied physical, sexual, racial and cultural experiences of the marginalised) would rather us all feign uniformity for their comfort. Nevermind soaring hate crimes – 72.1 percent of which are committed by White British people in 2015/16, according to the Crown Prosecution Service’s 2016 Hate Crime Report. No matter the rise of the far right in a number of European countries, nor the recent election of notorious bigot and accused rapist, Donald Trump as the next president of the United States of America. Reminding the most societally dominant groups of their failure to foster a culture of genuine inclusivity, is the real crime here, apparently.

Flitting between a shallow understanding of the fact that discrimination against othered people exists, and what he sees as unwarranted and insensitive bashing of global white dominance, Jenkins attempts to bolster his argument with a hypothetical favourite among those whose long-enjoyed privileges are brought into question: How would you feel if the tables were turned?

“What if I were to follow ‘hideously’ with black, female, Jewish, Arab, obese, disabled or Welsh?” he muses, as if we don’t already live in world in which this is a reality. As if the long-ascribed hideousness of the existence of the “other” is not the basis of the foundations on which many nations around the world were built. As if proclamations of an inherent moral as well as physical hideousness among the black, female, Jewish, Arab, obese or disabled for example, are not covertly relayed through media professionals like Jenkins, who only seem to have the capacity to tolerate anti-discrimination efforts as long as the rallying cries of those affected are not too loud, or too long.

Positioning himself as a champion of general compassion, Jenkins moves on to suggest that the real danger in speaking out against the ongoing dominance of older white men in society is inadvertently, or perhaps intentionally, enforcing a generally ageist agenda. Imploring people to think of “the third group of the damned”, who are apparently “less robust” than white men have been having found themselves the object of the frustrations of the marginalised, Jenkins suggests that anti-discrimination is solely a concern of young people. In Jenkins’ mind, the elderly, an apparently monolithic group devoid of any of the characteristics that expose specific groups to the aforementioned injustices, are more concerned with being thought of as human first.

“Would it not be better just to call people people, and find something relevant to say of them as humans?” Jenkins pleads at the conclusion of his piece, of course ignoring the fact that donning the badge of the “default” – i.e. being considered by most, a fully-rounded, yet entirely nondescript “person”, is an advantage experienced by a select few.

In answer to the question, I have to ask, Mr Jenkins, rather than taking issue with being considered part of the problem, would it not be better for you, as a self-proclaimed PMS, just to listen to, and I mean really listen to different types of people, and recognise the relevance and legitimacy of their varied experiences as humans?