New UK legislation being debated in parliament about data protection rights (the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR) includes an exemption for immigration enforcement. This would subject migrants, documented and undocumented, to racial discrimination, and further the culture of divisiveness encouraged by the country’s regressive immigration policy.

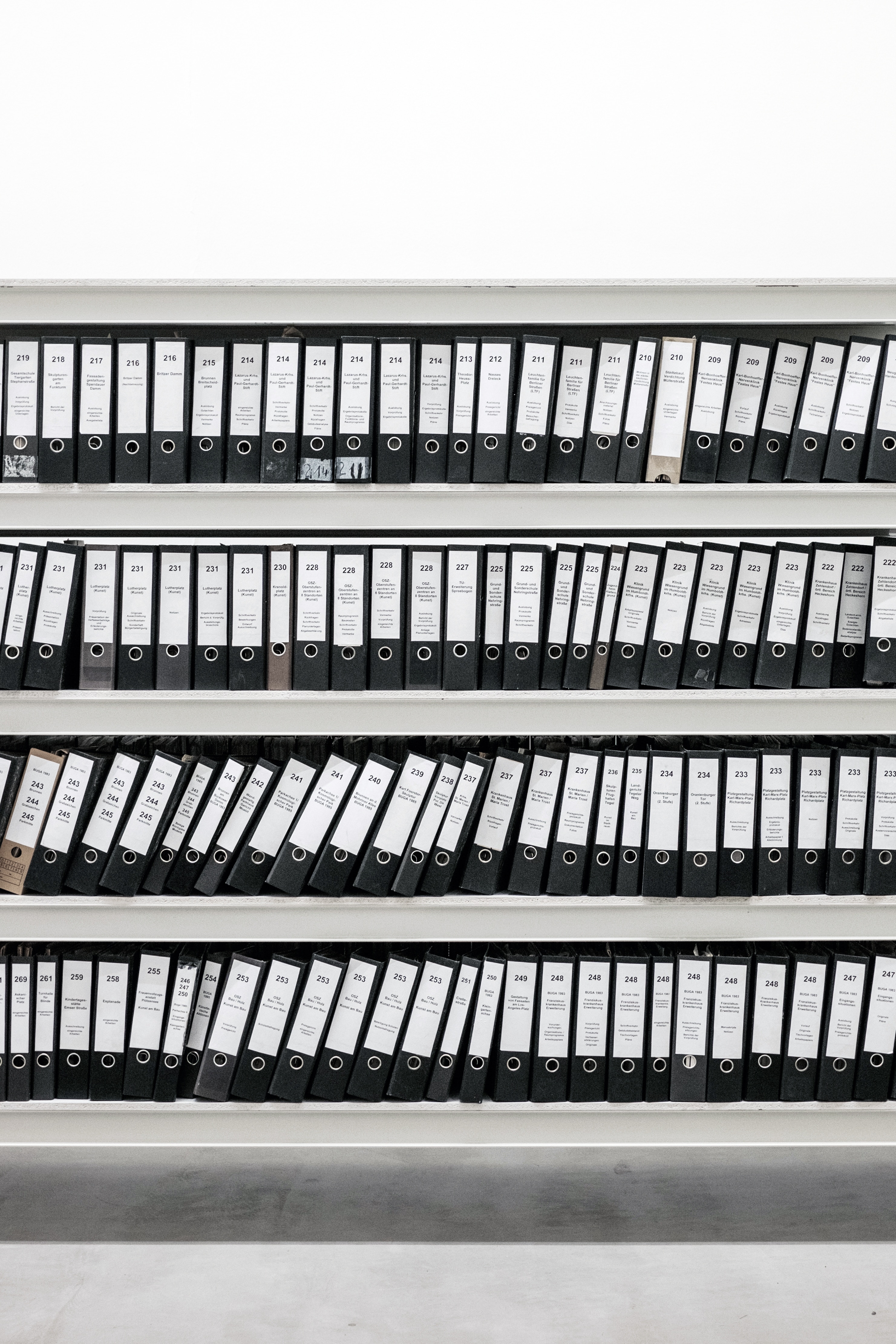

GDPR is the EU regulation protecting how data, including personal data, can be used. Post-Brexit, the government wants to keep close links on data with Europe, and so proposes to bring the regulation into UK law through the Data Protection Bill. The objective of the bill is to update the UK’s data laws, including enforcing individuals’ privacy rights, in light of how the internet has made masses of data more available than ever before.

The regulation, and the bill that would bring it into UK law, will confirm principles on how our data ought to be handled by those who have access to and control over it. It will also outline the rights of the individual in relation to their own data and how it can be processed, including the right to access personal data and to know how it’s being used.

Part of the GDPR gives EU member states the power to create their own exemptions to the regulation. For example, personal data can be used, irrespective of an individual’s wishes, by journalists or organisations doing academic research. These exceptions are, arguably, justifiable. However, Schedule 2, Paragraph 4 of the most recent iteration of the bill is cause for concern, as it sets out the exemptions to data protection rules for the purposes of “effective immigration control”.

This, in effect, means that an individual’s data could fall outside of the protection of GDPR if they are suspected of breaching immigration controls. Liberty, a UK human rights and civil liberties campaign group, has also warned that this could mean that the Home Office and other government agencies will be able to obtain and use personal data gathered for purposes unrelated to immigration control.

This exemption will deprive undocumented migrants of the same rights as citizens. Furthermore, it will also weaken the rights of documented migrants living in the UK who are suspected of being in breach of immigration law. As this group will often be of a “minority” ethnic background, the bill therefore has the potential to effectively allow a type of racial discrimination.

A similar clause was removed in the drafting of the Data Protection Act 1983: Clause 28 of the 1983 bill set out exemptions on the basis of immigration control. This was removed before the legislation was enacted; when debated, it was commented that this exemption was “in danger of being oppressive [and] deeply worrying to the immigrant community living among us”. This threat has been resurrected in the Data Protection Bill 2017, and its impact could be greater due to the Home Office’s current stated policy of constructing a “hostile environment” for migrants.

The 2014 Immigration Act introduced a range of measures intended to create an environment in which it would be difficult for undocumented migrants to exercise the same rights and access the same services as others. For example, the 2014 Immigration Act introduced a duty on banks to conduct background checks, including immigration status, of those looking to open an account. Additionally, it imposed a duty on the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) to revoke driving licenses of any license-holder whose immigration status was in doubt.

Such measures are also likely to disproportionately and prejudicially impact those from black and minority ethnic (BME) communities both by the scrutiny imposed in the first place, but also in the negative impact when errors are made. The Home Office’s track record so far is poor: 10% of refusals to open a bank account were made on incorrect grounds. And yet, the government persists in rolling out similarly hostile policies, including those enforcing the use of data gathered by public bodies for the purposes of immigration control.

These measures are unacceptable. In practice, they are state-sanctioned discrimination which stops migrants accessing vital services such as medical treatment and education. They are also pernicious as they put obligations on private individuals to act as border enforcement officials. This both ignores the individual’s own views, and fosters an atmosphere of divisiveness and mistrust.

In response to this, a number of organisations have launched campaigns to stop further harmful immigration legislation. Doctors of the World, Liberty and the National AIDS Trust have launched a petition decrying the use of NHS data for immigration purposes, and Docs not Cops are campaigning to remove passport checks in healthcare settings. Similarly, the Against Borders for Children campaign and the National Union of Teachers have set out their objections on how data collected by schools can be used, and a grassroots campaign, No Borders in Banks, is seeking to prevent data collected by banks from being used for immigration enforcement.

In this climate, it is even more pressing that we speak up to ensure that we all have the same protections from inappropriate and unwarranted government interference. It would be fatuous to immediately draw parallels with the DDR, but it’s worth remembering that information in the wrong hands can be used to devastating effect. As Satbir Singh, chief executive of the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants has said: “Why should migrants be denied the right to have their information processed lawfully, fairly and transparently?”

“Othering” depictions of migrant communities in national news media are already troublingly dehumanising. Rights over data may seem abstract, but they’re still rights and the government would be wrong to deny them.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?