‘Being Black, Going Crazy?’ shows we need more conversations about mental health

Tahiera Overmeyer

08 Oct 2016

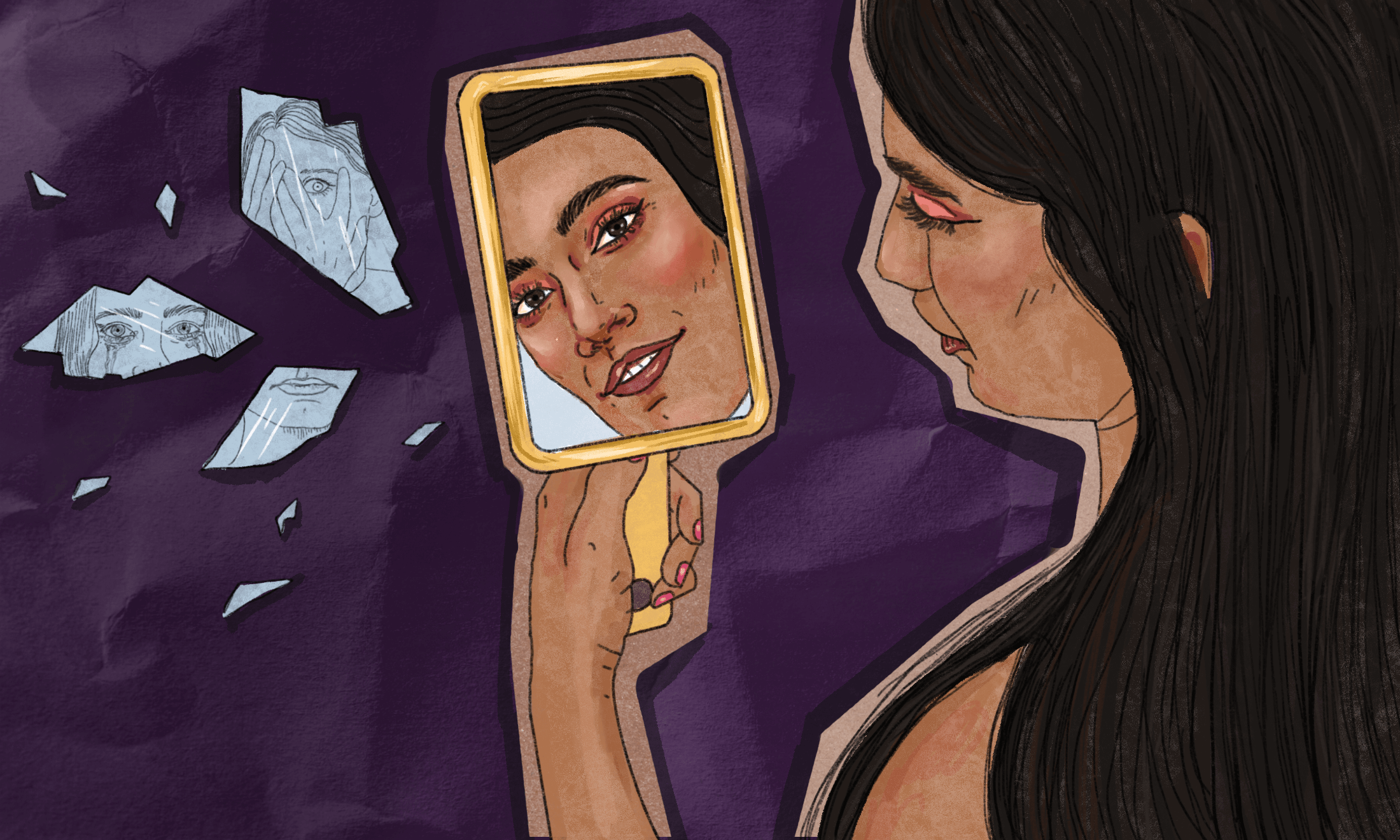

It’s only when you get older that the childhood view you had of your “normal” family gets shattered. All of the family secrets seem to come out. At 18 I found out that numerous close family members struggling with mental health issues – most commonly clinical depression. Before then, mental health had been treated as an “adults-only” discussion. It was spoken about in whispers, like a dirty little secret ready to be swept right back under the rug. The loudest thing said was, “I’ll pray for them.”

Dialogue surrounding mental health issues is often hushed in the black community, leaving little room for greater understanding of people’s experiences, triggers, or treatments. Writer and radio host Keith Dube challenged this in January 2015 by blogging about his depression and sparked a discussion. Now, more than a year later, his platform for conversation has been extended to a BBC Three documentary. Being Black, Going Crazy?, which explores the stigmas and causes of mental health issues in the black community; unfolding the stories of three people whose lives have been affected by it. Working from the staggering statistic that black men are six times more likely to be sectioned to a mental health hospital than white men, the documentary proves that the silence definitely needs to be broken.

The socio-economics of impoverished neighbourhoods is a factor that Dube touches on throughout the doc – growing up in this environment is something that can impact the psyche negatively. Although this sheds light on people’s surroundings playing a significant role in their mental health, the NHS, which costs around 4 percent of your salary, doesn’t always provide suitable care. Dube discovered that racial inequality exists in mental health treatment, and in the documentary we see psychologist Malcolm Phillips talk about this on Radar Radio with Dube, claiming that black people are much “less likely to get any talking treatment” due to practitioners perceiving black people as “more dangerous”. Unfortunately, biases are nothing new when diagnosing something as complex as the mind.

A well-known 1973 study, On Being Sane in Insane Places, investigated whether or not sane people can be diagnosed as insane and sectioned to a mental health hospital. Eight sane people approached hospitals claiming that they were hearing voices saying the words “thud”, “empty” and “hollow”. Rosenhan specifically chose to use these words as they allow interpretation for an existential crisis to be the issue. Beyond this, the only other aspects professionals were judging them on was the pseudopatients’ normal behaviour. It was found that completely sane pseudopatients were then diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

In addition to biases being a general existing issue in diagnosis, the cherry on top is clear from Phillips’ interview: blackness connotes madness to some medical professionals. People who work in a supposedly scientific, objective field are able to squeeze in preconceived, subjective notions about patients based on their skin colour.

Our voices should be loud and welcomed within our own families; isolation certainly doesn’t ease the experience of living with mental disorders. As seen in the documentary, many people feel that their parents won’t be supportive or understand that the mental battles they’re fighting may need more than a prayer or time to heal. In 2014 The Guardian interviewed an evangelical musician, Carlos Whittaker, about this after his own pastor advised him to stay silent about his mental health issues and others encouraged him to turn to his faith:

“I can pray 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and I’m still going to have to take that little white pill every single day,” he said. As shown in Dube’s documentary, in the black, religious community mental health issues are sometimes dismissed as anxiety that can be overcome or perceived as demonic, causing even further isolation.

Rapper Kid Cudi’s recent self-care choice – checking into rehab for depression – has also put black mental health in the spotlight via a Facebook post, “I am not at peace. I haven’t been since you’ve known me. If I didn’t come here, I [would’ve] done something to myself,” he wrote.

It has encouraged people in the black community to start the discussion. It’s raised questions about the pressure of masculinity, which seems to be a lingering issue for Kudi, as evidenced by his discussion of his depression in his recent iamOTHER interview. If one man can manage to inspire people to open up with each other by displaying his vulnerability on a global platform imagine what we can do in our own homes.

Whilst religion and mental health treatments are both ways to help the mind handle and embrace reality, it must be remembered that one does not replace the other. For some people, spirituality can be a way to begin breaking the silence about personal battles and believing in a higher power can feel like a proactive way to keep us sane when we don’t understand the dynamics of our minds or, even, this world. But for others, an appointment at the doctors might be needed.