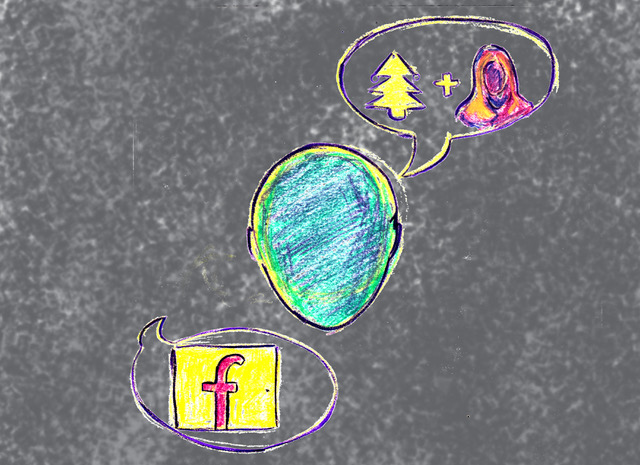

“You see what I’m saying, don’t you? It’s not about racism. I read on Facebook that Muslims are stealing Christmas trees from shopping centres and we can’t have that attack on our England. Do you know what I mean?”

Even now, years after this remark was made, I can still remember the earnest look on the face of the person who said it. We weren’t friends, but I knew her name. It was by chance that she’d decided to pick the chair in front of me in our form room, turning around to confront my brown face with information that she promised was true. These were the winter months of year 10: rife with conversation about GCSEs, unsigned planners, and the Muslim conspiracy that threatened to swallow Christmas day whole. Co-signed by the EDL and the Britain First Facebook page, of course. I can’t remember what my response to her was, though I imagine it was written all over my face.

Notions of nationhood, and latent xenophobia, have strong roots in our public consciousness and yet, in our school days, we did not have the right rhetoric to say what we felt politically. We could not condemn each other’s arguments over Twitter with 140-character rebukes, and did not attend many rallies (if any at all) with the same enthusiasm as we are able to now, as adults. Back then, political affiliations bled over class-mandated debates, into unspoken sentences at assemblies the mornings after someone else committed a tragedy whilst misconstruing Islam, and moments that saw the utterance of the word “Paki.” The air was always a little heavier after that. In the aftermath of the referendum which sawed Britain in half, I did not have to read analyses of Brexit to know why, or how, we’d gotten to this place.

Born in Bradford, and having gone to a school that straddled the border between Bradford and Leeds, hearing someone say that the Poles were dirty or that ladies in salwar kameez looked like they’d come out of a “jungle” was simply a backdrop of prejudice that none of us knew exactly what to do with.

Englishness, to be later emphasised in varying degrees by the likes of Nigel Farage, David Cameron and Theresa May, was a silent standard, left behind by previous socio-economic disasters. It was the product of a constant, producing cycle. It was weighed in glances and spoken out of loose lips, first heard at a young age, and nurtured by the authority that comes with parenthood. At school, some of us knew why it was easy for the popular kids to mimic a foreign accent. Some of us also knew why those with a heavier, rhythmic tone to their Yorkshire-isms could be treated to an affectionate, but belittling, jostling.

“You mustn’t be afraid to talk about race,” my favourite school teacher once said to a boy who shared images of drone strikes on civilian homes in Afghanistan on his social media. “It’s important to have these discussions.” Though they weren’t aimed at me at the time, I learned the impact of her words at university. I channelled the frustration of years of racial tension and class confusion into activism; the opening of dialogue upon dialogue. I am aware that studying at Cambridge University has given me a multifaceted vocal privilege: one which enables analysis of the signifiers of fascism, and which now seeks to realign Brexit, Donald Trump, and Marine Le Pen, with patterns of behaviour that can only be described as ill-informed.

Cambridge’s anti-Trump rally provided me with a solidarity that I had previously never felt as a visibly Muslim woman. But it was also tinged with the placid leftism of the privileged middle-classes. Though Cambridge is not without its problems of racism and elitism, it can comfort itself with the premise of education, and utilises intelligence as the ultimate defence for any of its mistakes. It remains rooted in this privilege to an evading degree.

When 2017 reared its head, it brought with it an awareness of narrative-making, conceptions of nationhood ready to be moulded by media rhetoric. The argument that the economically deprived are more likely to fall prey to the scapegoating of immigrants, to swallow swayed narratives, and vote in lieu of them is one which has been repeated often. However, it fails to account for the inherent logical flaw of the job-stealing immigrant argument, the stereotype of the dangerous Muslim, the prioritisation of social housing for an ‘Other’, and effectively, the pedalling of an Us vs. Them mentality. Being susceptible to scaremongering, or being able to break down the argument behind why such logic is flawed, emphasises a world of difference summarised in miseducation. But the dynamic of an open dialogue is difficult because it is unequal, and it is aware of its own difficulty in only being able to be spoken about as complex.

I thought about my teacher emphasising the importance of difficult discussions to a boy who spoke only of nationhood when I took off my hijab to get the train back home. I thought about articles written by experts on how universities were “safe spaces” for “special snowflake social justice warriors” after I went to an event on decolonising education; and later, when I was confiding in my Muslim friends about being terrified of being drop-kicked down a flight of stairs, like the grainy CCTV footage showed online.

The nature of a difficult existence in a difficult moment in history lies in interrogating it. The nature of today’s socio-political climate means it is difficult to do anything but. I used to think if I shouted loud enough, things could change. Now, I know what matters is not who is doing the shouting, but who begins to realise why the shouting ever sounded: what is being said, why someone listened, and why someone did not. Whether any one of us could learn to accept it. Whether it is possible for all of us to do so. Having to interrogate what the heavy past can signify as we emerge into an uncertain, heavier future may provoke more questions than answers; and yet, no one can say that the value in doing so is absent.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?