When she was 20 years old, my mother’s waters broke and she drove herself to the hospital to give birth to me, picking up her own mother on the way. I arrived six hours later, and 13 days earlier than planned. Soon after she had learnt that she was carrying me in her stomach, my biological father (I use that word loosely) decided he didn’t want anything to do with us. We spent the first four years of my life together in Salford, Greater Manchester, and it was here that she and I became best friends.

“I spent a large portion of my life trying to water myself down and erase the parts of me that aren’t white”

My mother is mixed-race. Her mother, my Nin, is a white Scottish woman, and her father, my Granddad who I never got to meet, was a black man from Belize in Central America. Just by looking at photographs I know that she and her father are almost identical – dark skin, thick curls, full lips and an undeniable look of strength in their eyes. My skin is lighter than theirs, my curls are looser, but I have the same lips, and have inherited their strength, though I had to nurture it over time. For my entire life, my mother has been teaching me lessons in self-acceptance, pride regarding our heritage, and how I should carry myself as a confident woman of colour. I was listening to her words, but somewhere along the line I stopped really hearing them, as the damaging words of non-POC began to drown them out. I spent a large portion of my life trying to water myself down and erase the parts of me that aren’t white – and it is only now, at almost 22, that I not only wholly accept, but have unwavering pride in who I am.

I watched a lot of Gilmore Girls growing up and I was besotted with the relationship between Lorelai, the ultimate cool young single mom, and Rory, the academic daughter. I’d watch, amazed at how similarly it mirrored our own life, our closeness, our sarcasm – the only difference seemed to be how easy things were for them, yet we struggled. Lorelai was a successful business owner, and Rory went to private school, and on to Yale. My mother is an extremely talented cook, but didn’t have the opportunity or qualifications to work in this field, instead working minimum wage jobs. I was achieving A* grades but being bullied at school for having brown skin. Ah, I thought when re-watching episodes a couple of months ago.

They’re white, and we’re not. That’s the biggest difference between our families. They would know the kind of life that was out of reach, but I would watch with wide eyes – the Gilmores had weekly Friday night dinners in the mansion and they would pass their coats to a maid and have their food brought to them. My mother would cook our dinner for us from scratch, every night, whilst we sang along to Erykah Badu in the kitchen. My mother half-watched an episode or two with me as she typed away on her laptop, and plainly remarked that we had the better deal. She was right, but I was too jealous of the chandeliers and the pool house to agree.

“The girls that sat behind me in the classroom began leaning forward, sniffing my hair, laughing and protesting that it smelt weird. I was mortified”

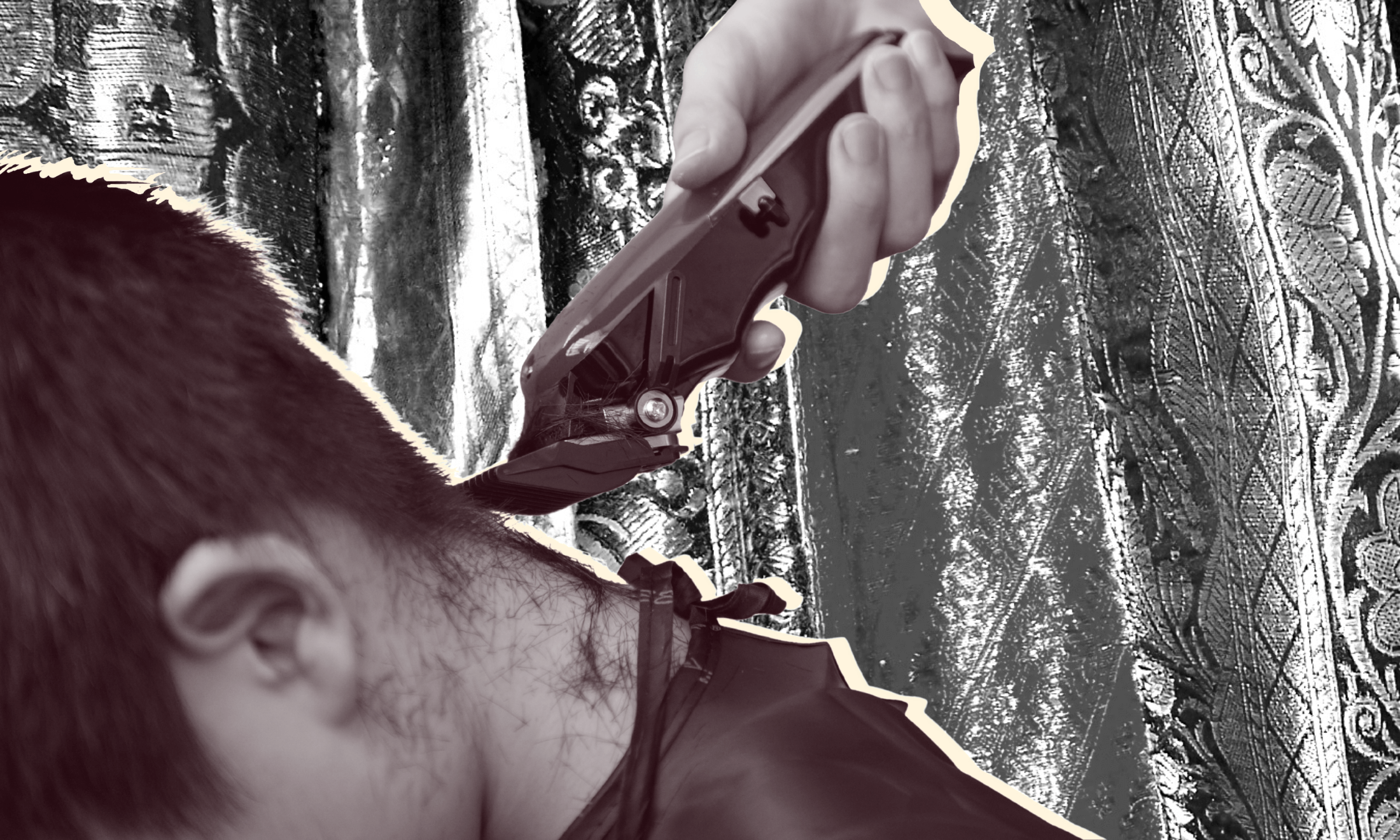

Every day before primary school, my mother liked to plait my hair into two braids, using a thick serum that had a woman with Afro hair on the label. She secured the braids with bobbles that had small glittery cubes on the end. My hair stayed put all day, and I felt pretty. One day, the girls that sat behind me in the classroom began leaning forward, sniffing my hair, laughing and protesting that it smelt weird. I was mortified. When I got into my mum’s car, I cried and told her she couldn’t use it on me again. She told me they were just jealous of my textured hair. I wouldn’t let it go. She was only allowed to use water on it now, and bits of my hair would stick up and go frizzy. The girls had found another reason to laugh, and I locked myself in a bathroom stall, licking my palms and patting my head, trying to flatten my hair back down.

High school wasn’t any easier for a brown girl trying to know herself – I loved writing, I loved reading, but more than anything I wanted to fit in, so began bending myself out of shape, desperate for approval. I’d gained textured hair during puberty, a beautiful, natural curl. I looked like my mother, but it was too different. I straightened my hair everyday, used cans of hairspray, tried to mimic the loose messy buns of the girls in my class. I had hairy arms, I shaved them. I had thick eyebrows, I tweezed them until they were two very thin, unsightly arches. I applied concealer to my lips instead of accentuating their shape. I bought foundation that was too light for my skin. I did everything I could think of to mirror the white girls, but it was never enough.

“She took me under her wing and I couldn’t believe her confidence in the things I resented about myself”

I began seeking hobbies away from school. I took an acting class during the weekends, and the best actress in the group was a girl called Bianca, about three years older than me, and she was black. She took me under her wing and I couldn’t believe her confidence in the things I resented about myself. I changed my profile picture to one of the two of us. A girl in my maths class referred to her as “n****r lips”, and I was ashamed for the both of us. At home, I cried, my mother cried, and I couldn’t identify with a single character in Gilmore Girls. I stopped watching it. I had lost myself, and I’d lost the battle. On the last day of school, I left the field in tears as the girls I had tried so hard to become shouted “p**i” at me. They didn’t care to find a correct slur. I wasn’t white, so any old word would do.

My mother and I are still best friends. It took her a lot of work, but once I was out of school, she remained focused on teaching me to love myself for who I am. She would tell me stories of what it was like when she was growing up, the harassment her parents faced for daring to be an interracial couple, the looks and the comments she had learned to brush off. Now I just had to embrace it. My mother achieved her goal and we bonded, perhaps later than she had planned, over the wonders of coconut oil and the awful lack of black, asian, and mixed-race cast members in the majority of television shows. I was introduced to old episodes of My Wife and Kids, and the Def Jam comedians. I could relate, whilst recognising my mixed-race privilege over those darker than me. I fitted in, whilst feeling the need to be strong for my fellow people of colour. I took on the role as confident, but still learning.

“I love the things about myself that I used to hate. I learn as much as I can about my ancestry, my roots, my heritage”

Today, I’m an adult. I’m a proud woman of colour. I split my hair 50/50: half natural curls (using a serum similar to the one my mother used on me when I was a little girl), half conditioned and blow dried and straightened. I love myself equally in both forms. I wear less makeup. I accentuate my natural features. I love the things about myself that I used to hate. I learn as much as I can about my ancestry, my roots, my heritage. I work to bring more visibility to people of colour. I believe in telling my stories, to establish representation for other brown girls trying to love themselves. I love my mother’s strength, because it was everything I needed to find my own.

Princess Nokia’s Flava video begins with a beautiful monologue, which includes the words, “First they make fun of you. Then they want to be you.” I searched for the cruel school girls on Facebook – they use bottles of fake tan, they spend their money on trying to gain thicker eyebrows, thicker hair, curlier hair. They listen to black music. They inject themselves with lip fillers, but I say nothing. I just hug my mother.