In October, Kid Cudi (real name Scott Mescudi) announced on his Facebook page that he had “checked [himself] into rehab for depression and suicidal urges”. The post, which has since received over 400k likes, explains how “ashamed” he feels to have been “living a lie”, and he admits, “I am not at peace. I haven’t been since you’ve known me… My anxiety and depression have ruled my life for as long as I can remember”. Mescudi was described by Kanye this year as “the most influential artist of the past 10 years”, has sold over 5.2 million digital singles, has a successful acting career, and still finds himself crippled by anxiety.

Mescudi is just one example of the growing numbers of those who work in music struggling with mental health issues. In November, Help Musicians UK published the findings of its research into the mental health of those working within the music industry. 71% of respondents believed they had experienced anxiety and 65% had dealt with depression. This follows a small wave of popular musicians who have come forward to talk about their personal experiences with anxiety in particular, and in doing so, have shed light on mental illness in the industry.

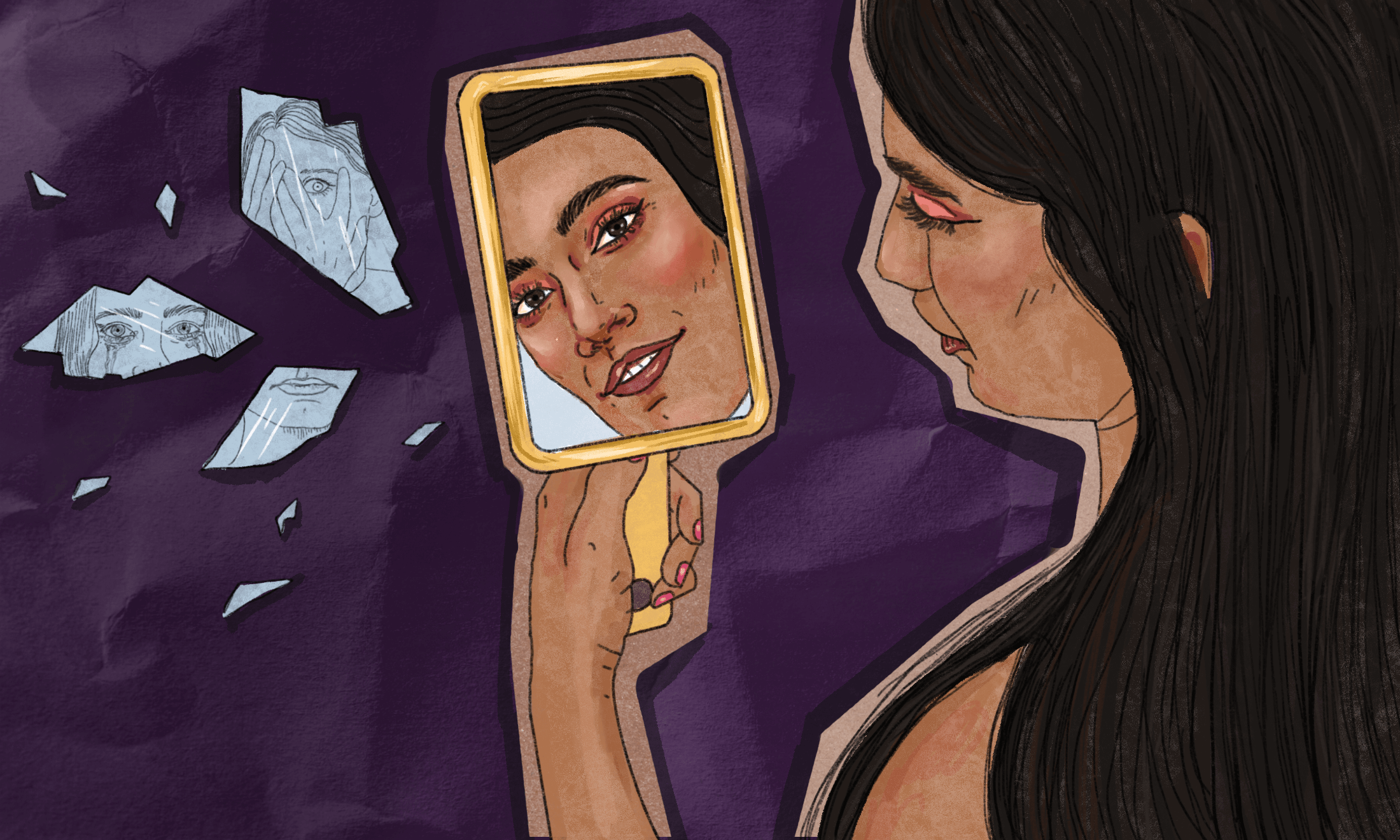

But one thing troubles me: what happens if you’re famous, suffering from anxiety, and not white? It’s something that isn’t often been touched upon, but it seems that stigmatisation of mental health is far more obvious when the sufferer is a person of colour – and often that stigma comes from other PoC.

After Kid Cudi spoke out about his anxiety – and also beefed with Drake and Kanye on Twitter – Drake dropped ‘Two Birds, One Stone’, a diss track apparently directed towards Cudi: “You were the Man on the Moon, now you go through your phases / Life of the angry and famous”. As expected, Drake received a huge backlash online. To mock and belittle mental illness as a “phase” – especially as a response to some petty, insignificant tweets – was seen by many to be reinforcing the stigma and supporting online hatred. But in reality, Drake was just reflecting what many others were saying.

@TheAffinityMag @TheOptimistMe thing is this bastard isn’t just mocking cudi he’s mocking millions suffering from clinical depression

— Tibian (@TibianBahari) October 24, 2016

@TheAffinityMag rap ain’t got time for feelings

— ChicharitoElSalvaje (@ThatChicoCCake) October 24, 2016

There is a worrying lack of empathy which is harmful and discouraging for those who battle with mental health issues and are speaking out to mainstream media. Just before Christmas, after Kanye cancelled his tour and was hospitalised for exhaustion and paranoia, he was trolled online. There was a sense that he somehow deserved it, as though mental illness is some sort of punishment.

History proves that a white lens is often been needed to be the voice of reason on a social stigma for it to be taken seriously. The whitewashing of the suffragette movement, for example, shows that moments of courage in the effort to tackle societal prejudices are often taken more seriously when white people are allies to those speaking up. To address this issue, to get people of colour heard properly, heard first – there needs to be more support that, for the meantime, is noticeably absent.

That is not to say that white artists haven’t struggled to come forward about their anxiety either; as long as mental health is stigmatised (and even after it isn’t), trolls will still be there to demoralise and disgust. This also does not mean to say that their struggle hasn’t been just as hard, and that their decision to speak out isn’t brave.

But it just seems that for many artists of colour, there isn’t space for being vulnerable whilst being in the spotlight. Listening to musicians of colour who have made it to the mainstream, and all I hear is strength. Even after being cheated on, Beyoncé is confident – “boy, bye”, “they don’t love you like I love you”. Even when being played, Drake extolls his upset with a whininess that suggests confidence and self-assuredness: “why you gotta fight with me at cheesecake you know I like to go there”; “I’m just saying that you could do better”. Artists of colour shouldn’t be reluctant or even frightened to discuss their mental health, worrying whether or not anyone will support them if they do speak out, or if they’ll even be taken seriously. Zayn Malik told ES magazine “Anxiety is something people don’t necessarily want to advertise because it’s seen, in a way, like a weakness.” This, fundamentally, is the attitude that needs to be carefully dismantled, shredded into tiny pieces, and then smashed into oblivion.

It’s not all bad. The most openly, unapologetically vulnerable artists in my music library at the moment are Kendrick Lamar and Frank Ocean; both of them suffer from anxiety. Kendrick and Frank have left a trail of breadcrumbs, in so many different and far-reaching ways, which delineate paths creative, social and artistic for others to follow.

I listen back to Kid Cudi’s ‘Day ’n’ Nite’. I remember being at school when it came out and listening to it on the way home, thinking it was so upbeat. Now I look at the lyrics and it makes me sad.