2017 has been a pretty tumultuous year for marketing to communities of colour. When we were presented with the catastrophic Pepsi and Shea Moisture campaigns back in April, we thought it was all over. But despite the shaky start, the year has presented a number of industry-defining moments that point to a more optimistic and inclusive future of advertising. And now in what seems like an interesting way to finish off the year, we’ve been presented with the most mixed-race Christmas in British advertising history.

First and foremost, as a mixed-race woman working in advertising, the vast number of Christmas ads this year featuring happy scenes of multiracial couples and families has left me shook, and I’m feeling optimistic. Some of the biggest UK brands did away with the traditional all-white Christmas this year to instead embrace romantic scenes of multiracial couples dancing in the snow: Apple’s “Sway” for Airpods, Euan McGreggor-narrated adaptations of Cinderella and her black prince for Debenhams, and heroing young black and mixed-race children in a feat of Christmas storytelling (hurrah Morrisons, John Lewis, M&S and H&M).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1lGHZ5NMHRY&authuser=2

The significance of this, in an age where brands and agencies have a long way to go in representing and reflecting an increasingly diverse Britain, should not go unmissed. In 2015, a study conducted by Marketing Week found only 5.65 percent of British ads featured black people, 3.86 percent people of mixed-ethnicity, and 2.71 percent those of Asian descent, despite 18 percent of the UK population identifying as being of Black or Asian heritage. In many ways, this merry multiracial Christmas signifies a progressive step towards achieving greater representation and inclusivity of people of colour in the popular narrative.

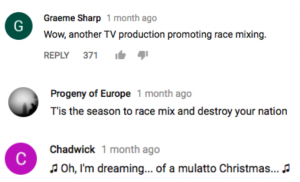

Naturally, this year’s Christmas ads have been met with a vicious swarm of racially-charged and hateful comments, proving further the need for brands to continue creating more inclusive ads that help to normalise the presence of people of colour in mainstream communications. All it takes is a brief flick through the Youtube comments (or what is left of the comments following brands’ mass-deleting spree of the worst) to grasp that the usual friendly, gushing and festive responses have been replaced with white cries for boycotting the “offensive” string of multiracial Christmas adverts.

Take this year’s John Lewis ad Moz the Monster. Other than the lead child being played by a mixed-race boy, the creative concept is pretty much identical to John Lewis’s 2014 ad Monty the Penguin. Both follow the story of a young boy and his relationship with an imaginary friend, but comparing the public reception to both ads (Monty the Penguin received 2000 dislikes versus Moz the Monster 13,000 dislikes) reveals a long list of sarcastic comments equating multiracial advertising with political correctness and the promotion of “race-mixing”. It is in this context that I’m thrilled brands and advertising agencies alike have actively incorporated more POCs in this year’s Christmas marketing.

Often when it comes to featuring POCs in advertising, we are a product of “diversity afterthought” in the creative process. The question of greater ethnic or cultural representation arises in the later production stages (e.g. casting), rather than in the earlier creative development phase. This means that POCs tend to be retrospectively fitted to scripts and storyboards, rather than written into them. The result is often an ad which neither taps into a real truth about the audience the brand is trying to target or represent, nor represents POCs in an interesting or authentic way.

When it comes to representing POCs in creative campaigns, agencies need to spend greater time in the earlier planning stages fleshing out the cultural insights that reveal a real truth about different ethnic and cultural groups: our attitudes, behaviours, lifestyles, to better inform a creative idea. Authentic representation of POC is then more likely to be achieved in the later production stages if the people both in front and behind the camera are themselves of a diverse background.

This Christmas we’ve seen the marrying of the idea “modern family” with the mixed-race family on an industry level. In turn we have also seen the mixed-race family equated almost exclusively to the model of the white-black multiracial family, and the vast majority of these ads (excluding H&M and Morrisons) have cast white women with black men as the parenting leads/couples. With this in mind, the industry’s visual representation of the multiracial family is in danger of falling neatly in line with a broader “acceptable diversity” agenda.

We are still battling with the effects of advertising’s long history of normalising white beauty standards. Although in recent years there has been notably more representation of POCs in ads and communications, brands and agencies continue to sway predominantly towards lighter-skinned actors and models when it comes to casting. Mixed-race women are popping up in beauty ads left, right and centre, but we are still waiting on greater representation of dark-skinned black women in advertising across the board. So, whilst I feel visually accounted for as a person of mixed Antiguan and white British heritage, the industry’s understanding and representation of the British “modern” family could do with broadening their horizons to be more inclusive of British families of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black, and East-Asian origin.

Advertising plays an important role in shaping the way we see ourselves written into the mainstream narrative. Ads like the ones we’ve seen this Christmas are important for ensuring that younger children of colour, like my nine-year old sister, can see themselves represented, and their existence normalised, in popular culture, where I as a child did not.

Growing up in a split family in the multicultural city of Leicester, my identity was shaped by a world that was predominantly black or white. To see a mixed-race family in an ad was a rarity, to see a woman of colour in a hair or beauty ad even rarer. Now, we are seeing progress in the way that brands and agencies are diversifying their creative content, but there is still much more to be done. Thankfully, the continued emergence of creative spaces of colour and agencies like Looks Like Me are helping to push the boundaries and reshape the way advertising agencies cast and represent POCs in communications. Fairy-tale depictions of families of colour whilst heart-warming, should not exclusively be reserved for Christmas.