Last week would have been my brother’s 37th birthday, although you wouldn’t have guessed it. There was no cake or family dinner, and in fact, no mention of the occasion even passed between myself and my father. Jonathan, my brother, died when I was five years old. I rarely speak about it, but have become better at being able to do so over the years. He was a few months shy of 21 when he died, and whilst I’ve been able to graduate, move house and get a new job, I am constantly aware that these are the things Jonathan was about to do before he was denied his right to embark upon his adult life. Sometimes I wonder what could have been, what he would be up to and if he might have had a family of his own at this point. But what has struck me, now more than ever, is the difficulty that my father has speaking about what happened to our family, and his reluctance to approach or mention the subject of my brother.

This summer, my father and I packed away the things in Jonathan’s room, many of which have been left untouched for the last 16 years. We placed his ice skating trophies, ice hockey jerseys and his paintings, now all neatly organised, into those stackable clear plastic boxes, all the while only saying minimal meaningless chit-chat to each other. I found a folder full of documents relating to the traumatic circumstances that surrounded Jonathan’s death, and chose to stay quiet. I packed it away into the box with all his other things – this folder that had his death certificate in, newspaper cuttings about his death that my mother had saved, the police report. All these things that I so desperately wanted to speak to my father about but feared that I would be met with a one-word answer and a stony silence, as has traditionally been the case when it comes to Jonathan.

A couple of days after my brother’s birthday, evoking such strong feelings in me and barely an acknowledgement from my father, I attended the Southbank Centre’s Being A Man Festival 2016 – it seemed like the timing was fate. Initially, I went along to try and do some research for an article on masculinity and mental health. I’d been wanting to explore this topic for a while, and talking to my male friends in the days beforehand, knew that it was an important conversation to have. Male suicide is the biggest killer of men aged under 45 in the UK, with three times as many men taking their own lives compared to women in 2015. While commemorative days and months can sometimes seem patronising and tokenistic, important campaigns around men’s health, specifically male mental health, have traditionally taken place in November by organisations such as The Samaritans, Campaign Against Living Miserably(CALM) and Movember. These campaigns have done amazing work in recent years of highlighting issues that are nowhere near as well reported, researched or even simply talked about as they should be.

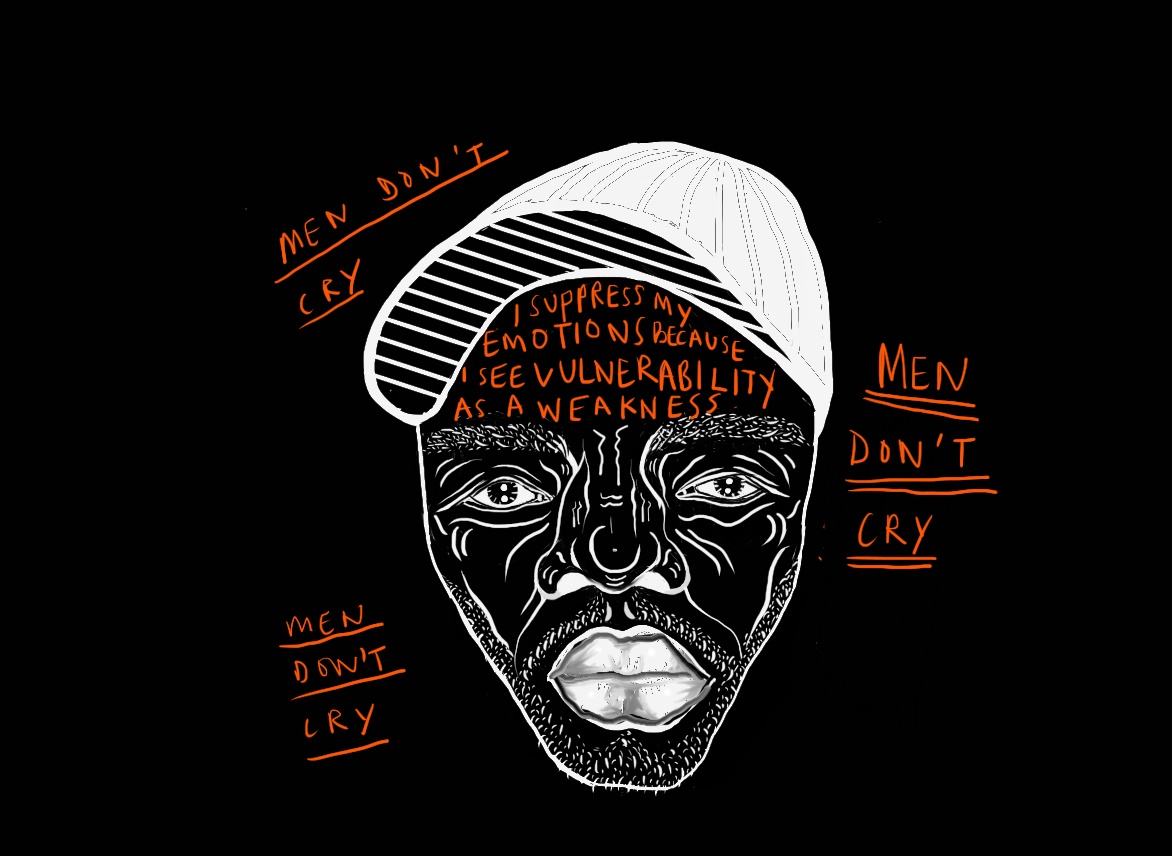

So I went to the festival, hoping to ask some probing questions about how feminist movements and male advocacy campaigns can work together, and to get to the bottom of the message behind International Men’s Day. Instead, I found myself attempting to control that familiar choking feeling in your throat when you’re holding back tears, whilst attending a panel discussions that, of course, was called ‘Boys Don’t Cry’. And as I was listening to the panellists speak about their experiences with depression, grief and suicide, it dawned on me that their words had provoked my unexpectedly visceral reaction because I recognised that what they were describing was the behaviour of my own father. The shame they had felt in expressing their pain, the destructive reactions to triggering events in their own lives, the unbearable pressure to keep up appearances and “be a man” – it all sounded too familiar.

Jonathan was my father’s golden boy, his “anchor” as my mum once put it. And after he died, my dad lost his way. In some ways, I don’t think he’s has been able to find it since. I recall my mother once telling me that she had encouraged him to seek help from a support group, but this suggestion was slapped down by a family friend, another man, who said to my dad “You don’t need any of that therapy stuff, you’re strong, you’ll be fine.”. My parents had just lost their son in an unexpected, tragic way, and my father’s emotions were simply dismissed, as if it was something that could easily be brushed off. I feel a sting of anger even now as I write, thinking what that exchange must have been like to experience for my father, to feel like he couldn’t talk about our insurmountable loss. No-one would really call my father a wallflower – in fact, in many ways, he’s the opposite. When we’re around most people, he’s theatrical, embarrassing (as all dads are!) and the life and soul of the party. I just want him to know that I understand why he does that, why he acts in this way – and that I understand why he does not want to acknowledge the reality of what happened.

Masculinity has traditionally been a societal stereotype directly opposing the negative stereotypes of women that we’re all too familiar with. Men = strong, protector, provider, invulnerable. Women = fragile, emotional, delicate, weak. Yet as Jack Urwin so brilliantly put it in his 2014 article ‘A Stiff Upper Lip Is Killing Men’ and his follow-up book entitled Man Up: Surviving Modern Masculinity, the knock on effects of this tight-lipped, keep-your-emotions-under-lock-and-key expectation of men can quite literally be fatal. Comedian and CALM Ambassador Jack Rooke tells me that “my female support network worked better than ever trying to talk to my older brothers” after Jack’s father died when he was 15. “For my granddad, the bereavement was really traumatic to the point of triggering dementia in him. The loss can accelerate the process, and he just suppressed his pain so much…eventually he started to think that I was my dad.”

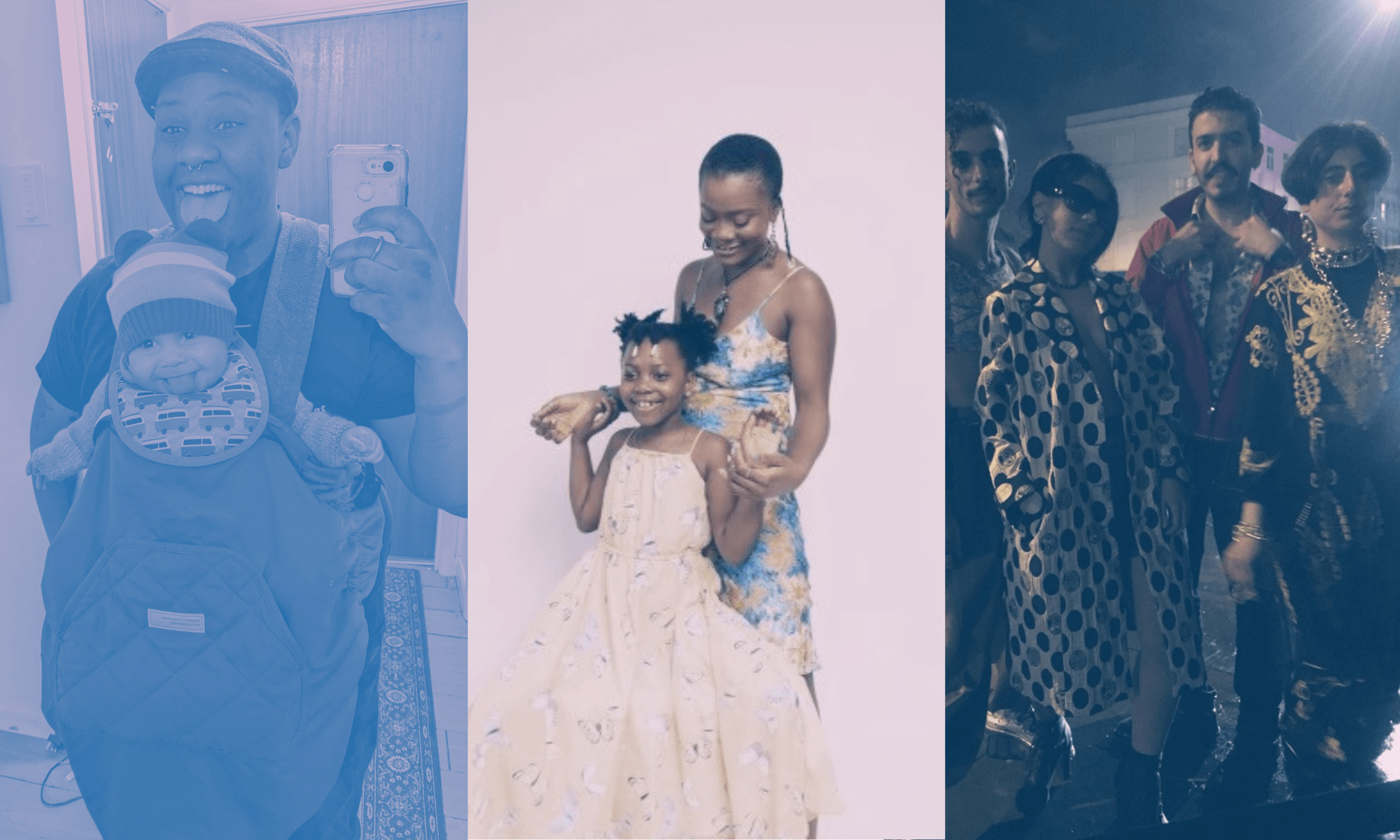

The Southbank Centre’s festival was not, as one troll on Twitter attempted to mansplain to me, a gathering of man-hating sexists. Being A Man defines itself as exactly the opposite. Over the weekend, I listened to men open up about the most personal, intimate details in their lives as they explored and celebrated what it means to be a man in the 21st century. The festival showed me just how heterogenous masculinity can be. It can be the honesty of Jack Rooke as he speaks about grief after his father’s death, or it can be Jonny Robinson discussing his campaign to find the man who prevented him from taking his own life. It can be So Solid Crew’s Ashley Walters revealing his parenting secrets, or it can be the inimitable Grayson Perry wearing a dress while smashing the white middle class heterosexual male gaze. Masculinity is such a multidimensional, diverse concept – but only if we allow ourselves to see it that way.

My brother, all that he was and is, is an unspoken taboo between myself and my father. I don’t think we have ever had one honest, meaningful conversation about Jonathan as a person, let alone his death. I have only seen my father cry on a handful of occasions throughout my lifetime. Grief for my father, as for many men, is so difficult to come to terms with precisely because it renders you vulnerable to emotional, agonising reactions that you cannot control. I can see the burden of grief he carries, and sometimes I simply wish that he would share it with me, to lighten the load. On the second day of the festival, I listened to Grayson Perry voice his thoughts on masculinity. “Vulnerability is the absolute key to men having a better time in the future,” Perry said, and that resonated with me so much. To hear men speak so candidly and frankly about their experiences struggling with depression and grief was powerful, precisely because they were allowing themselves to be vulnerable. I hope one day, as painful as I am certain it will be, my father will feel that he is able to do the same, and to hopefully share it with me.