Growing up with a drug addicted parent is isolating, and what I still find surprising is that it feels like no one talks about it. Of the 105,780 people receiving treatment for substance misuse during 2011-2012 in the UK over 50 percent were parents. Yet even today I feel like I’m alone in having a parent who is physically present but not mentally.

With my dad what started off as casual opium taking with an employee turned into addiction. Iran suffers from the second most severe opium addiction rates in the world, so it’s not massively surprising that his Iranian employee was using. They would sit in the flat above the pizza shop my dad owned and smoke opium, speaking in their mother tongue, reminiscing about memories of their life past in Iran, until there was no turning back and he was addicted. When seeking help, my dad’s doctor prescribed him methadone – a bright green liquid he would pick up from the pharmacy every morning, and now subutex, a white pill.

I always remember how at seven years old I was looking for a friend who had a dad like mine, a dad who slept all day and night, contributed little to the family, and had to go to the pharmacy every morning to pick up his drug (or as we refer to it in my house “medicine”). When my best friend in primary school said her dad slept all day I was relieved – I thought his behaviour was finally confirmed as normal – until she said he worked night shifts. It soon became apparent to me that my dad wasn’t “normal”, and I wasn’t going to be able to talk and relate to others about having an addicted parent.

When he was awake he was erratic and unpredictable – he might be extremely high and take us to Toys “R” Us to treat us, or get angry at something small and throw the coffee table across the room. As a result of his behaviour I was permanently on edge, something I wasn’t even aware of until recently. I needed to be on my guard because I could never predict what mood he would be in. I don’t remember a time when my dad wasn’t addicted to a drug, so I’m still not sure if his behaviour is part of his personality or his addiction.

***

My mum was so ashamed about his drug use that she told us to tell no one. I diligently kept this secret until I was 19, firstly because it was an embarrassing secret to tell, and secondly, because it was an awkward conversation to have with people. That said, the silence of it all made it harder; I had to think of excuses for his behaviour.

“Why does your dad not work?”

“He’s unwell,” I would say half-heartedly. Or, “he’s retired.”

Luckily, no one seemed to press further.

I thought I had a handle on it – I’m aware his addiction has nothing to do with me, and I’m also aware my family and I cannot change his ways. We supported him through his attempts to stop, but his doctor giving him the drugs readily meant that he would always go back to it.

It wasn’t until, age 19, that I spoke to someone outside of my immediate family about his addiction and realised how much it affected me mentally. I met someone, my best friend, who I felt understood what it was like to have a strange home life – or at least he was open about it. I knew he wouldn’t judge me for my dad’s addiction or gossip with other people about it later. I could trust him. But, the first time I said the words “my dad is addicted to drugs” I still burst into tears.

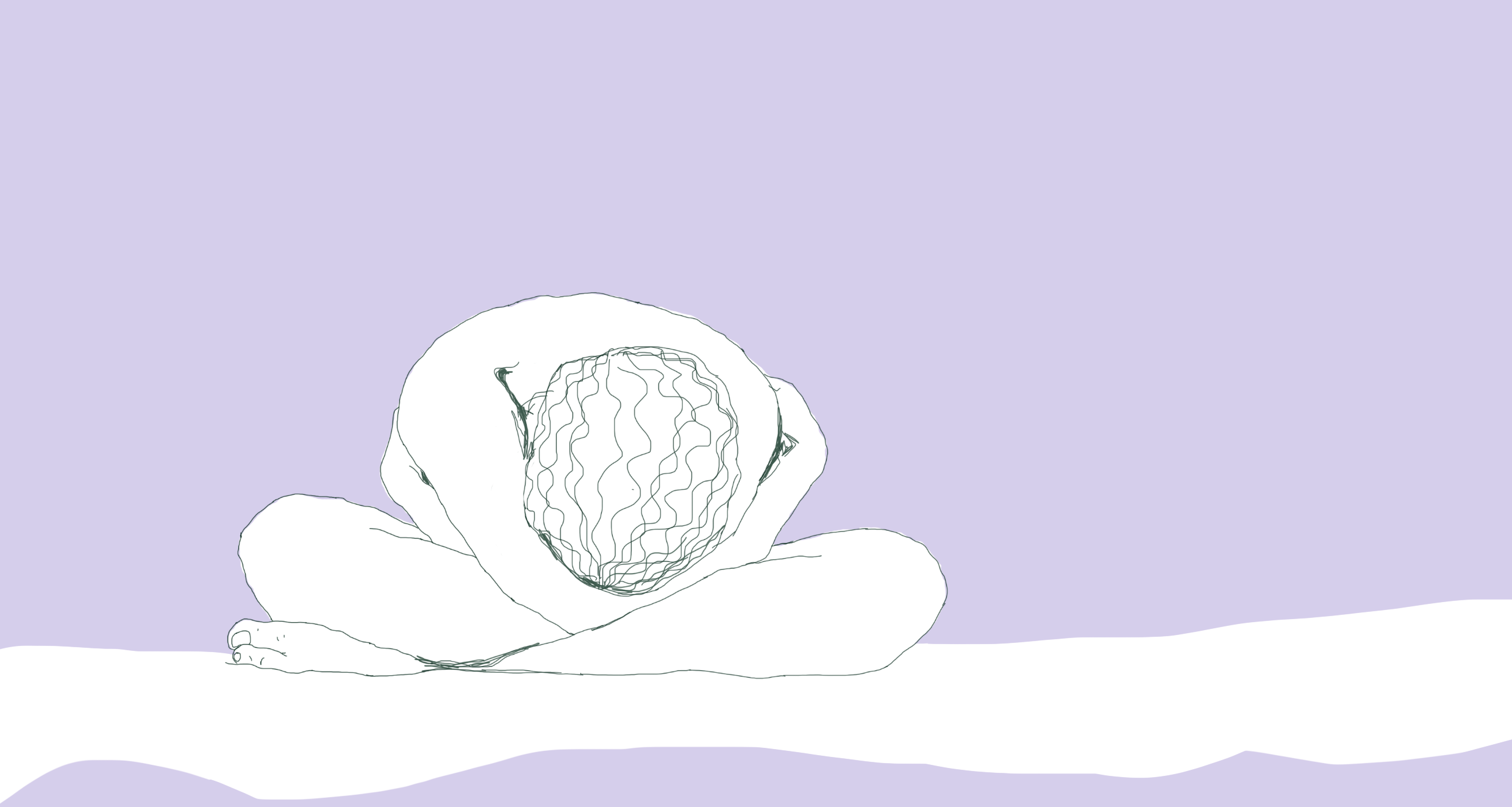

What comes with being the child of a drug-addicted parent is the lingering anxiety about what is to come. It’s dull in the back of my head and it means it’s rare I feel relaxed. Even today, when I haven’t been living at home for five years, I still peel the skin from the side of my nail when I’m given a moment to think – a sign of my neurosis. It feels weird to be carefree. I am always thinking my situation could suddenly change and something bad could happen.

***

When I ask my mum what my dad was like before the addiction she says he was much the same, except he worked, but I wonder if she’s forgotten over the past 20 years of addiction. At the moment he stays at home every day, watching crime documentaries and movies whilst my mum works. When she comes home he expects food to be made immediately.

He made my mum a single parent, and he became the fourth child in the family. I felt the disappointment of not having him at parent teacher days, of him not taking an interest in my life, of him not being there at my graduation. He was absent, even though he lived in the same house as my family; even though we saw him daily. I became more reliant on myself from a young age, as I got the sense that I was unimportant to him.

In a way I still feel like this; when we speak it is always at a superficial level, and I wonder whether that is because he cannot communicate properly because he is never at a right head space. I get the feeling that he is always thinking about something else. I do blame him for his addiction because I feel if he did really care about us he would at least try; he would care about how his behaviour affects us. In taking opium the first few times he made a choice, albeit one I’m sure he didn’t think would change his entire life, but a choice nonetheless. I do not see him necessarily as a victim because I am so conscious of how difficult he made our lives, and also how unapologetic he is about it.

***

When I was 21 he tried to stop taking drugs for a month. His whole demeanour changed; his voice was softer, his face less red and angry, and for the first time in my life he asked me how I was and actually cared. He listened, and seemed human. This gentler side of his personality surprised and pleased me, until I realised that although he had stopped taking subutex for that month, he instead got opium from a friend.

So, whilst we cannot change the actions of others, only support them when they try and be better, I think the silence around this issue needs to be broken. When I spoke to my mum about writing this piece she was encouraging, which surprised me. She said people need to know how their actions affect their children.