Once upon a time — though it’s quite a timeless tale, really — within the pages of an erotic romance novel, a young heroine – Rosy, comes into full bloom. In present-day Bhopal, India, in the privacy of her bedroom a widowed 55-year-old landlady known to all as Bua-ji (Aunty) reads Rosy’s story furtively. As Rosy’s story unfolds to Bua-ji, the lives of the four main heroines of Lipstick Under My Burkha begin to unravel as their private desires are made public.

Just looking at the film, you expect colour, drama, and excitement. With its use of a voiceover to narrate Rosy’s story, a cast that is like a dysfunctional extended family (the four leads live with their families in the same old housing complex, where Bua-ji is both landlady and matriarch figure) with bright, almost gaudy, sets bathed in primary colours, Lipstick Under My Burkha is structurally and stylistically reminiscent of a Wes Anderson family drama – far more so than any other mainstream Bollywood film I’ve seen.

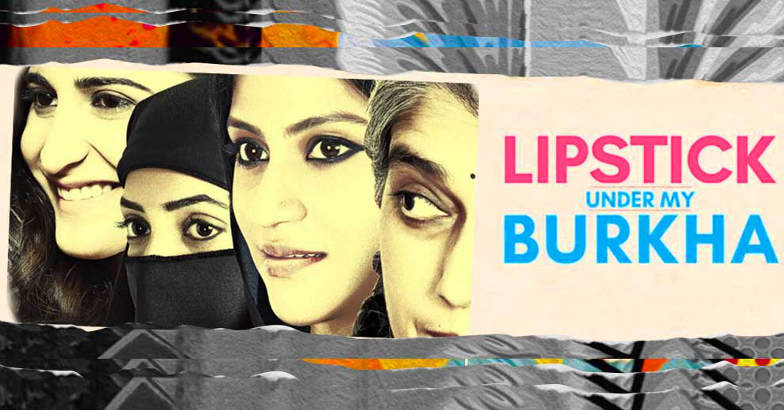

“India’s film Censor Board refused to certify Lipstick Under My Burkha … deeming the story ‘lady oriented, their fantasy above life’.”

Despite its title, Lipstick Under My Burkha is not about the garment itself; the burkha seems not to hinder the two characters who wear it, but allows them to move through their public lives inconspicuously. This not only ensures their survival but also enables their success. Rather, the title has to do with what is concealed – and the consequences of exposure. According to director Alankrita Shrivastava, it refers to “the things that women sometimes do in secret because they are not allowed to do them in public. […] the title is about hidden dreams, secret fantasies and hidden ambitions”.

The series of romance novels featuring Rosy is titled Lipstick Waale Sapne (“Lipstick Dreams”). Shrivastava has stated that in her film, lipstick represents women’s rebellion. But it is not an infallible tool of resistance. Lipstick is certainly a consistent and striking detail throughout the film, but it too can be smeared and is wielded to entrench patriarchal societal expectations.

Earlier this year, India’s film Censor Board refused to certify Lipstick Under My Burkha, thereby initially denying its local release. In a rather incoherent statement, they deemed the story “lady oriented, their fantasy above life”. This controversy undoubtedly contributed to the hype surrounding the movie, which finally released in India in July to a largely positive critical response. The film was promoted via a savvy #LipstickRebellion marketing campaign, initiated by Balaji Motion Pictures, which encouraged posting photos on social media while holding a lipstick in one’s middle finger. Male actors further consolidated their support via the #MenForLipstick movement.

Let’s be real: even with its initial share of challenges, the (eventual) support of prominent industry figures Prakash Jha and Ekta Kapoor, and its high production value and big-name stars like Ratna Pathak Shah and Konkona Sen Sharma, Lipstick Under My Burkha is not exactly an underdog film. It is not groundbreaking in speaking for (nor does it claim to) all intersections of marginalised identities — for example, queerness, disability, or illness are not discussed. It is most readily reminiscent of other recent big Bollywood films that touch on social issues concerning women, like Queen (about a woman’s independence and freedom outside the institution of marriage), Pink (about sexual assault and victim-blaming rape culture) and Dangal (about empowering women through sports). One way in which Lipstick differs from these films is that it is directed by a woman. Shrivastava herself has deemed Pink and Dangal “steps forward but not disruptive”, for in both, a man (played respectively by high-profile actors Amitabh Bachchan and Aamir Khan) is central to the narrative. In Lipstick, Shrivastava doesn’t pander to male audiences. Most men in the film are portrayed in an unflattering, though believable, light, and are not offered redemption.

Popular Indian cinema needs to push further precisely so that a film like Lipstick, even without discounting its merits, is not seen as the be all and end all of “daring” filmmaking. The #LipstickRebellion is not quite the radical liberatory feminist revolution we need. But under current conditions in which women are still punished for articulating their desires, and patriarchal forces (not just men, but also other women) hold power to actively block, even if not support, them from realising their dreams, the film is perhaps useful in seeding this awareness into public consciousness.

The Indian film Censors’ comments are somewhat accurate in guiding us to where Lipstick Under My Burkha succeeds best: in its exposure of the consequences that each woman faces not even for pursuing her desire in secret, but for daring to do so in public. For each of the four main protagonists, the aspirations they name are regarded as “fantasy above life”; the very speaking up that initially empowers them later leads to their downfall.

Throughout the film, what struck me was not the women’s lipstick so much as their hands. Their fingernails, often immaculately painted scarlet red, draw attention to the hands: running cloth through sewing machines to stitch burkhas, holding the camera that films them making love, wrapped around a microphone on a stage, a beer bottle in a bar, a cigarette in the dark, wielding kitchen utensils and clutching children’s hands, and turning the pages of the romance novels through which they breathe Rosy’s dreams. Lipstick may be striking but it can be smeared, and to re-apply it is a choice. But all throughout, humble hands are bearing witness, continuing to do the labour that is not even necessarily about escaping, or dreaming, or even silent protest, but simply about survival.