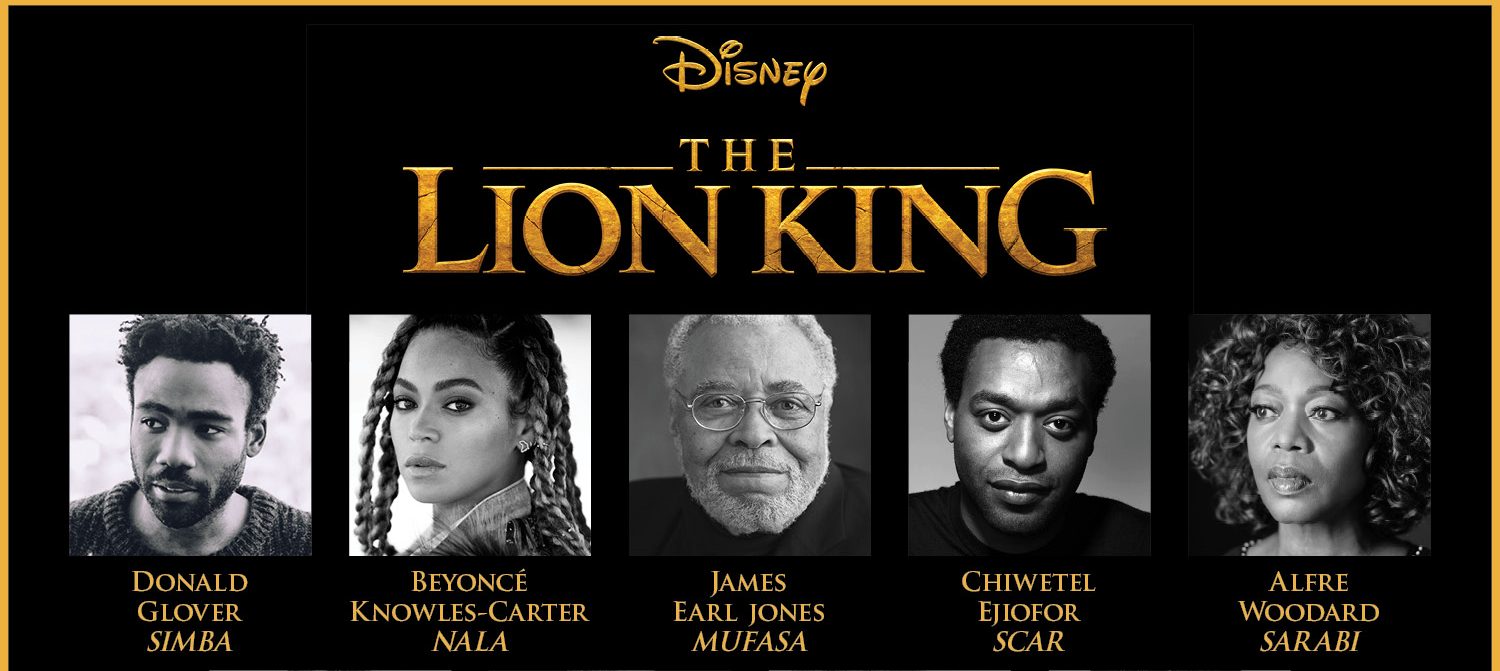

The 2019 movie remake of The Lion King has been confirmed, making way for another majority-black cast in the realm of musicals.

But “black musicals” and “black roles” can be problematic, especially when considering the presentation of the characters that black actors so often play. The lack of diversity in characterization leaves talented black actors typecast in roles such as “wise old man” and “sassy momma” or even “zebra”, “giraffe” or “lion” as is the case in The Lion King. These portrayals of black characters are hangovers from colonial and racist stereotypes of blackness. People of color are seen as comical, are marginalized within narratives and in the worst cases shown to be “inhuman” – that is to say, animals.

Perhaps this criticism is too harsh on what is a theatrical realization of a children’s film about the animal kingdom, but the idea of Africa as a wild and untamed terrain inhabited only by animals is a dangerous one that reinforces colonial ideas of civilizing a savage land. To depict these animals with almost exclusively black actors also sets a worrying precedent. It could, on one level, be considered more appropriate to use black actors to represent ‘African’ animals, but it is also worrying that these animals seem to perform the same “rituals” and exhibit the same social relations as those, imagined in colonial discourses, of the “the natives”. The concept of the tribe and the chief, portrayed through the allegory of the Animal Kingdom, is one that is associated with blackness in the post-colonial European imagination.

“The concept of the tribe and the chief, portrayed through the allegory of the Animal Kingdom, is one that is associated with blackness”

Aside from the issues associated with the narrative of the Lion King production, the whole concept of the all-black cast seem to justify the lack of diversity in wider, more mainstream musical theatre shows. The traditional musical has a tense relationship with race but so too does contemporary showbusiness and, more specifically, casting directors. Even as an amateur, as a women of color, I have found myself repeatedly told that I do not “look right for the part” or actually more subtly that someone else has “better connected with the character”. This may be simply because I am not as good an actor as I would like, however I also see that the roles I am cast in fall into a pattern.

In musical theatre, the roles for women of colour, and black women in particular, are constrained to the following: older women in authority, sexualized other women or “the friend”. All of these roles must be accompanied by what the business term “sass” The head teacher with a sassy side; the best friend with a sassy side, even the mother superior with a sassy side. The stereotype of black women in musical theatre is concrete and pervasive, even as a chorus member I am expected to be the belter, the one who can riff in the middle of a number. There are certain skills I am expected to have by virtue of my blackness that are there simply to add some “sass” and cynicism to an otherwise heartfelt and sincere performance by the white leads.

“Even as a chorus member I am expected to be the belter, the one who can riff in the middle of a number”

This brings me to the lack of women of colour in the role of the love interest. In the context of an all-black cast, it seems more acceptable that a women of colour might be sincere, complex and desired. Opposite a white man however, it seems too implausible, maybe even too political to have a women of colour who is understood to be the object of his affections. I have certainly found that I have never been cast as a romantic interest. I have, however, been cast as a prostitute, a head teacher, mother superior, a secretary, a best friend and a barmaid, all of them accompanied with the instruction to be “sassy”.

The problem with The Lion King’s majority-black cast is not so much its existence but rather that it is used as an escape valve for the rising racial tensions that still pervade musical theatre casting both professionally and in an amateur setting. They alleviate the growing pressure for musical theatre to catch up with the rest of society and stop typecasting black women and women of colour in stereotyped roles. Whilst white actors continue to enjoy a variety of roles and characters, which is after all one of the main pleasures of acting, black women are relegated to portraying the supporting role. We are left with the laziest of script writing: uncomplicated, one dimensional characterisation. As black actors, we cannot settle for simply always being in a “black musical” – we must push for more meaningful roles and challenge racist and stereotyped casting norms, we must not let our talent go to waste on unimaginative characterisation.