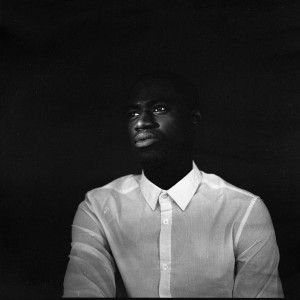

I recently stumbled across the work of young black British photographer Juliana Kasumu and instantly fell in love. Trawling through Juliana’s Instagram account I was immersed in an abundance of melanin with black and white film photographs exploring the beauty of black British culture. With Juliana’s work, it really is true when people say that ‘a picture speaks a thousand words’. Acting like a total fan girl I reached out to Juliana through Instagram and asked her to be our next artist feature. We discussed education, exams, art and how Americanised our accessible history materials are:

Juliana is a 23-year-old fellow South London girl of Nigerian heritage. While she was growing up, in Deptford, she attended Addey & Stanhope School. Juliana has now graduated from Birmingham University where she studied Media and Communications and is currently working full-time

as a freelance photographer.

Juliana’s journey into photography was not inevitable; she told me how being of Nigerian heritage meant there was an expectation for her to embark on an academic career path. “Coming from an African-Nigerian household it was very much growing up you know, you need to be an engineer, doctor, lawyer or something academic. It’s funny, I didn’t realise … really know that I wasn’t an academic.” At A-Level, Juliana decided to take photography as a welcome break from her more ‘academic’ exploits. Little did she know that photography would turn out to be her most fulfilling and challenging subject. With fondness, she described how she had finally found her ‘thing’, a channel to express what she didn’t feel comfortable doing so through words.

Juliana paid homage to a particular A-Level teacher who had encouraged her to pursue photography at university. She explained how she “hadn’t been told before that I had potential, she saw a great deal in me and I owe her a lot. She taught me about the whole process of film photography as well, she taught me how to capture good frames, and she taught me about all the photographers who inspire me today.”

When speaking to Juliana, there was a warm familiarity about her; we are both London girls who, now in our twenties, are beginning to discover who we are as black British women.

Juliana’s photography acts as a way for her to connect with and discover more about her Nigerian heritage. She told me that despite having grown up with parents who emigrated from Nigeria to the UK, their primary focus had been on bettering her education – something I’m sure many young black second-generation Brits can identify with. When I reached a certain age, I was surprised by how little I knew about who I was and where I came from. Similarly, Juliana told me that she was “shocked at how much I didn’t know about where I came from”. She added that every undertaking “is like a research project, I’m investigating and researching more things, using photography as a vessel to tell these stories”.

We discussed how when undertaking research in order to counteract the white-washed narrative of history we are fed here in the UK, most of the materials available are frustratingly America-centric. “When I do undertake research, it’s very much stuff from America. The books I read, the articles I read are very much African American and you hardly… Obviously it’s out there, but the black British experience isn’t so easy to discover. It’s important for me to highlight these issues from the black British experience and perspective. I feel like there is such a gap in the market for this sort of thing, it’s amazing to see other young British artists out there doing their thing.”

It was around this time that Juliana discovered the type of photography which was for her, black and white portraiture. When she started at university, she explained: “I thought I was going to be some hot-shot fashion photographer. Within the last year (of university) finding out about my Nigerian heritage that I had no idea about, I went on this rampage almost. It was like an epiphany; I just decided, okay I’m going to use photography as a way for me to tell my story. We can get mad and frustrated about all the happenings, feeling like people of colour in Britain especially are under-represented. But what are you actually going to do about it? So my thing is okay, what am I going to do to make sure they are represented? I’m going to make sure these stories are going to be told.” Juliana’s unwavering determination to tell her story in the form she is most comfortable with is what drew me to her work to begin with.

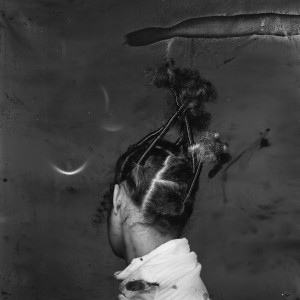

An example of her determination to capture otherwise untold stories is shown in Juliana’s ongoing project ‘Irun Koko’. ‘Irun Koko’ highlights the beauty of traditional Nigerian hair threading techniques through a series of powerful photographs. This particular project is used as an exploration of pop culture and fashion within contemporary African society. While ‘Irun Koko’ is reminiscent of the work of the late J. D. Okhai Ojeikere, Juliana didn’t come across his work until after she began the project. She recalled the moment she found his work: “I was like oh okay, alright this makes sense. I’m so glad to have found him. He’s a major, major inspiration for me in the standard that he’s set in African photography in general. It did clarify things for me; it proved that there was a story to tell here, for me to keep documenting.”

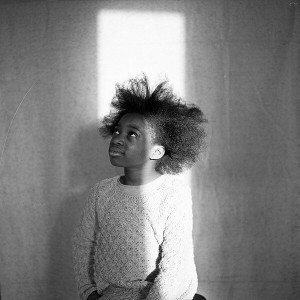

Another project of Juliana’s is entitled ‘The Next Generation’ which deals with young black British girls experience of haircare. We discussed the myths we are told about good hair vs. bad hair and our use of the creamy crack. Juliana made it clear to me that she wasn’t here to judge other women for choosing to relax their hair. Rather, she was concerned with how, growing up, our haircare choices were relatively narrow. Through ‘The Next Generation’ Juliana hopes to counter the negative language surrounding young girls with afro-hair of all textures. She told me that her frustrations lie in “how it is being used in contemporary society today. And a lot of people just don’t know. They ask why we get mad and scream cultural appropriation when white women wear cornrows. But it’s not about them appreciating it or not, it’s about it being used in fashion without any knowledge or understanding.” As black women we are sick of our hair being fetishised and its ‘coolness’ being contingent on white perceptions of it. She summed it up perfectly: “my history isn’t trendy.”

Juliana relayed her frustrations not only in the appropriation of black hair styles but also with the so called ‘natural hair movement’. “I hate, with a passion, the term. It’s not a movement, let’s not get into that. I hate the way how even then it’s turned away from appreciating our hair. It’s turned into another set of goals and insecurities. If your hair isn’t the perfect curl or 3a, it isn’t beautiful; you still see these European standards of beauty. So I have to call bullshit on that too. Yeah you can have natural hair but as soon as you cut off your relaxer it has to be down to your back and look a certain way.” Something I know myself and many of my ‘natural haired’ friends can identify with. Afropunk is great, but there tends to be one ideal style of afro which dominates across their social media channels.

Juliana’s projects are all shot on film, and she told me the reasons behind this. “With digital you see it, you’re shooting and you keep checking back to see if you got it right. With film you can’t check for anything, either you get it right or you don’t. And I love that, it feels like I’m taking a risk.” In fact, her winning image (right) for the Renaissance Photography Prize 2015 from ‘Irun Koko’ contains a line which wasn’t intended to be there. “And when it happened it felt like this was meant to be. It turned out so perfectly for me. I’ve had moments like that. Film has trained me to plan the frames and know that I need to get what I need to get, which is something I love about it. And, when I take the images and get them developed, it’s either like everything I wanted it to be or more. It’s like I’m doing the shoot again. I dunno, it’s weird. I like the process of shooting the film and developing it and printing it all myself.”

Juliana’s projects are all shot on film, and she told me the reasons behind this. “With digital you see it, you’re shooting and you keep checking back to see if you got it right. With film you can’t check for anything, either you get it right or you don’t. And I love that, it feels like I’m taking a risk.” In fact, her winning image (right) for the Renaissance Photography Prize 2015 from ‘Irun Koko’ contains a line which wasn’t intended to be there. “And when it happened it felt like this was meant to be. It turned out so perfectly for me. I’ve had moments like that. Film has trained me to plan the frames and know that I need to get what I need to get, which is something I love about it. And, when I take the images and get them developed, it’s either like everything I wanted it to be or more. It’s like I’m doing the shoot again. I dunno, it’s weird. I like the process of shooting the film and developing it and printing it all myself.”

Finally, Juliana explained how “with transitioning and learning about my history, my work is transitioning with me, I feel like my work is an example of me. I remember having a meeting with someone I had never met before. And for some reason, they were like I get the vibe from you that you shoot on film. ‘I was like giiiirl you have no idea’ She was literally spot on.” She laughed. “My work is literally a description of me.” Juliana’s personality certainly does shine through her beautiful photography, which is available online. I can’t wait to line my walls with her images of beautiful black skin. The spirit behind Juliana’s work in wanting to tell a story from the black British experience is one I can identify with.

Juliana’s work can be found here, on Twitter @lovekasumu and Instagram @lovekasumu