Sexualisation is a concept not unfamiliar to a significant proportion of female readers of this magazine, and females in general. We experienced it during puberty, when our breasts ached and protruded awkwardly, when our hips began to be defined through our clothing, when boys equated our worthiness to our bra sizes. Unfortunately, some of us experienced sexualisation even before puberty, when even shielded with the veil of innocence, men repeatedly perceived us as objects of sexual desire.

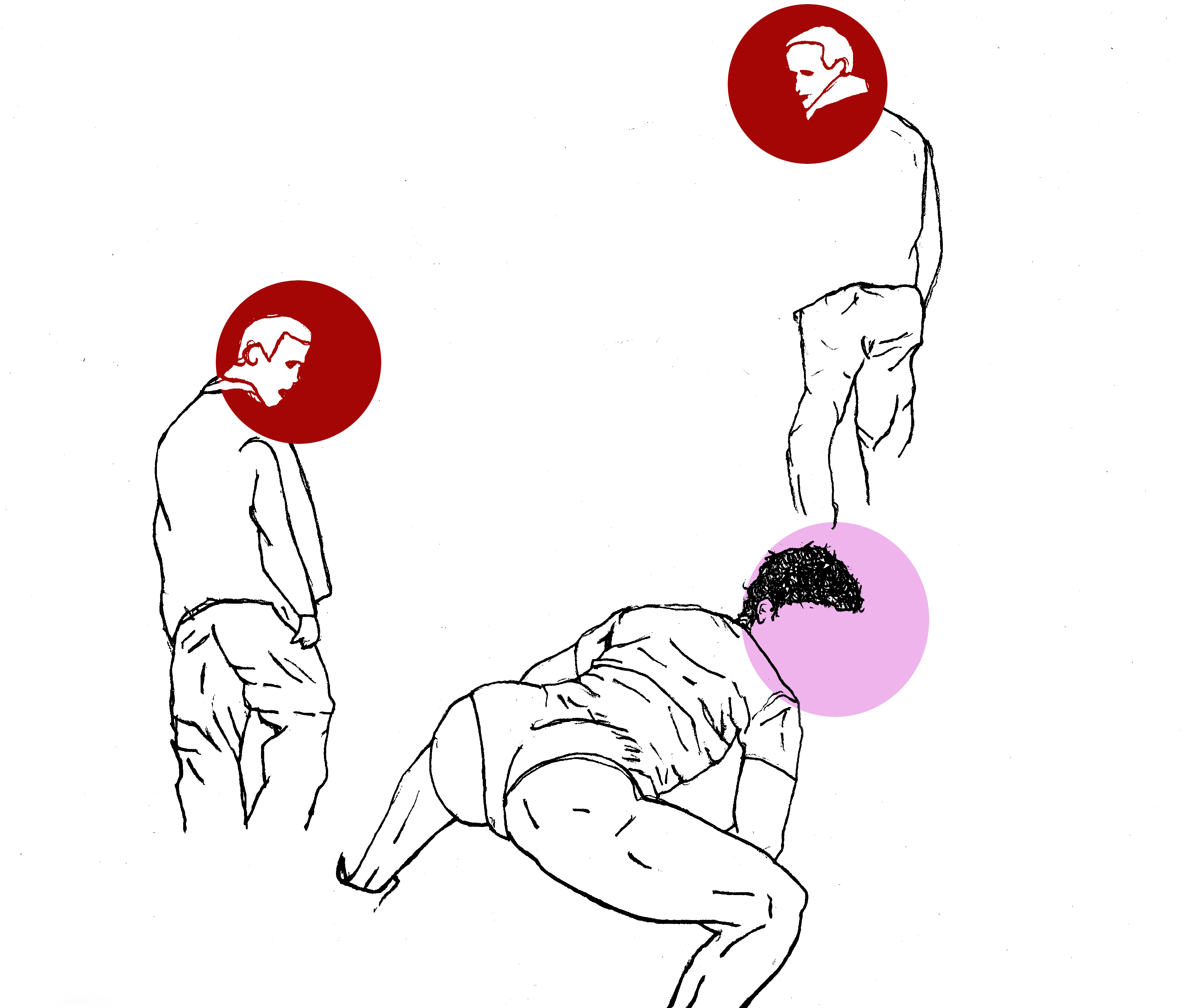

I had my own experiences as an object of sexualisation during this dreaded rite of passage known as puberty. I had just relocated to Kenya from Toronto and the telling glares I received from men, often twice my age, caused a churning in my belly and an incomparable embarrassment. I was embarrassed of my body and its ability to garner such unnecessary attention. What was I doing wrong that made it okay for these men to ogle at my rear and whistle in my direction? This was my first encounter with sexualisation, and I was only 10 years old.

Throughout my consequent years in Kenya, I grew uncomfortable with my adolescent body and adopted every measure to conceal its edges and curves: over-sized sweaters, unflattering baggy jeans, you name it. After eight years of trying to hide my body from the gaze of unwelcomed parties, I had almost become immune to the stares and comments. They still caused the same inner repulsion, but I regrettably became used to it. Living in Canada when younger and never experiencing this kind of explicit sexualisation, I naively idolized the white man as the height of decency. My then rudimentary understanding of sexualisation made me believe that he would never hold me to the arch of my back and the bulge of my breasts. My growing hatred of the Kenyan black man culminated as a result of their blatant sexualisation of my being. Upon this, I struggled to understand their simultaneous colourism – where my dark shade was only good to be crudely admired and never pursued. I was dark enough to be heckled at on the streets, but too dark to be romantically pursued. Collectively, these factors further fuelled my impression that sexualisation was not a concept white men condoned.

Three months shy of my nineteenth birthday, I found myself in the Netherlands pursuing a Bachelor’s Degree. I was based in conservative Maastricht, a small town in the south of the Netherlands, inhabited by very few other black girls. I therefore anticipated the stares and the whispers I received from the local population, as I was an anomaly. However, what I didn’t anticipate was the hyper-sexualisation and fetishisation. Whereas sexualisation is unfortunately experienced by all women simply due to our womanhood, hyper-sexualisation goes beyond these confines of womanhood and is exclusively experienced by women whose womanhood as well as either their race or ethnic background are linked to validate men’s objectification of them. Not only was I being sexualised, something I was unknowingly convinced I wouldn’t encounter from white men, but the sexualisation was also rooted in my race.

Being told to go for Dutch guys because “they really like black girls”, and strangers exclaiming “oh you’re gonna get black pussy tonight?” at any non-black male I was accompanied by, having my skin referred to as chocolate or cocoa, and discovering that there was a competition taking place between a group of boys over who would sleep with a black girl first were all realities of hyper-sexualization I came face to face with in my first year of college in the Netherlands. I initially mistook the comparisons to Naomi Campbell and other iconic black female celebrities for compliments. However, with further scrutiny, these supposed acts of admiration all appeared a facade as these men were simply placing my value in my race and the connotations that came with my race. I was expected to be a certain way and therefore my offense at certain remarks was an overreaction and consequently redundant. I pinned down this mentality to Maastricht being a small and relatively homogenous town in the south of the Netherlands, disconnected from the realities of diversity and new to the myriad of diverse faces that had begun to settle there.

At the beginning of my third year of my degree, I relocated to Madrid, Spain to carry out my exchange programme. Madrid, a cosmopolitan, capital city brought with it hope that I’d have the privilege of invisibility, and that perhaps for once my blackness and my womanness wouldn’t be so central in determining my person. I was completely mistaken. Within my first two weeks in one of Europe’s most populated and well-known capitals, I had my ass groped, was referred to as “morena” and “negra” (directly translated as “black girl”) by men wanting to assert their sexual interest in me, and was approached by males who presumed I was a sex worker. Never has my womanhood and race been so overtly sexualized like it was in Madrid. My misconceptions of Maastricht being a small town prone to such mentalities were proven to be wrong, as I encountered the same tribulations, if not worse, in a city with over 10 times the size in population. My misconceptions of the white man being the embodiment of respectability were wrong as not only did I face the same sexualisation – where my body became an object of desire – but my race was painfully interlinked, where said men felt entitled to their sexualisation of me simply based on preconceptions they harboured over how a black female is supposed to be.

We’re perceived as promiscuous, willing and accepting of whatever form of sexual proposition that is thrown our way. As a result, our reactions and objections are already silenced before we even express them. The sexualisation of black women not only has its roots in modern media, but is also rooted in the historical depiction of us. Historically, black women are perceived as objects of sexual exploitation, dating back to days of slavery where the concept of rape was never applied to the black woman simply because she was assumed to have been a willing and promiscuous participant. White women were the representation of sexual morality, whereas their darker hued counterparts were perceived as unchaste in their supposed invitation of sexual objectification. These stereotypes have lasted and have seeped into modern media and societal domains. Black women are often presented as raunchy video girls, baby mamas bearing children with unknown and often multiple fathers, and sexually willing characters often inviting of sexual objectification. These depictions transcend the confines of the media, and penetrate and manifest themselves in everyday society.

Because of the historical weight of the depiction of black women and the persistent perpetuation by modern media, it’s okay for a man to grab my ass in broad daylight, it’s okay for a man to call me a whore and deem me a sex worker and it’s okay for a man to approach me and whisper sexually crude remarks. Sexualisation and hyper-sexualisation are concepts many of us women of colour may never escape. So long as discussions are not generated and the media continues to maintain certain stereotypes, I may just live out the rest of my life perceived as the angry, sexual, unchaste black woman.