Taken from our print issue. Buy it here.

Technology and the internet have never before been so intertwined with our daily lives and, as a result, our selfhood has become as much an online projection as it is physical and psychological. The personal and political are indivisible from media and technology. For those of us with a smartphone, we carry a gateway to global politics and culture with us at all times, and many of us engage with some form of online media on at least a daily – if not hourly – basis. And it’s this constant interconnectedness that is beginning to play an integral part in shaping our realities, identities and behaviours.

These interlocking systems of identity, politics and society should also be analysed through an awareness of power and hegemony – the dominance of one system over another. For example, bell hooks describes the hegemonic framework we live in as ‘imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy’, commenting:

“I often use the phrase ‘imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy’ to describe the interlocking political systems that are the foundation of our nation’s politics. Of these systems the one that we all learn the most about growing up is the system of patriarchy, even if we never know the word, because patriarchal gender roles are assigned to us as children and we are given continual guidance about the ways we can best fulfill these roles.”

(I would update the description of the latter to ‘imperialist white-supremacist capitalist ableist cisnormative hetero-patriarchy’, although it doesn’t quite roll off the tongue so well.)

The policing of women’s bodies as a result of imperialist white-supremacist capitalist ableist cisnormative hetero-patriarchy is enacted online as much as it is IRL, perhaps even more, and often more aggressively. Anonymity plays a substantial part in this, as it distorts the accountability and implications of online actions, which is perhaps one of the reasons trolling is so pervasive. I found myself thinking about this recently when, late on a Monday evening, someone I’ve never met commented something uninspiringly unoriginal and sexist on a friend’s photo of me on Facebook. Why do I care about anything this boring man has to say? Because, like so many other boring men before him, he is exercising power and control at the expense of my own, and this toxic interaction is now showcased on the internet for all to see, his comment neatly tucked below a picture of my face.

“The policing of women’s bodies as a result of imperialist white-supremacist capitalist ableist cisnormative hetero-patriarchy is enacted online as much as it is IRL”

Instances of aggression, harassment or defamation often seem heightened online, due to the highly public nature of these spaces and the intense lack of control we experience when someone trashes us on the internet. As we spend so much time online and occupy these spaces as routinely as we would our homes, schools or workplaces, the impact of online interactions cannot be downplayed. A few weeks ago, my 13-year-old cousin mentioned that she wishes she didn’t have to grow up in the “Instagram era”. She told me that she doesn’t want to avoid it completely as she will miss out on connections with her friends and wider social media happenings, but feels pressure to look, act and be a certain way because of it.

Putting your best self forward at all times can have a negative impact on mental health, especially for teens. I am grateful that I didn’t have to grow up comparing myself to a constant stream of contoured models living their best life, although white beauty norms were particularly jarring when I was a hairy brown teenager. Women are held up to impossible standards of beauty and behaviour through most aspects of society, and the impact of this is only amplified online.

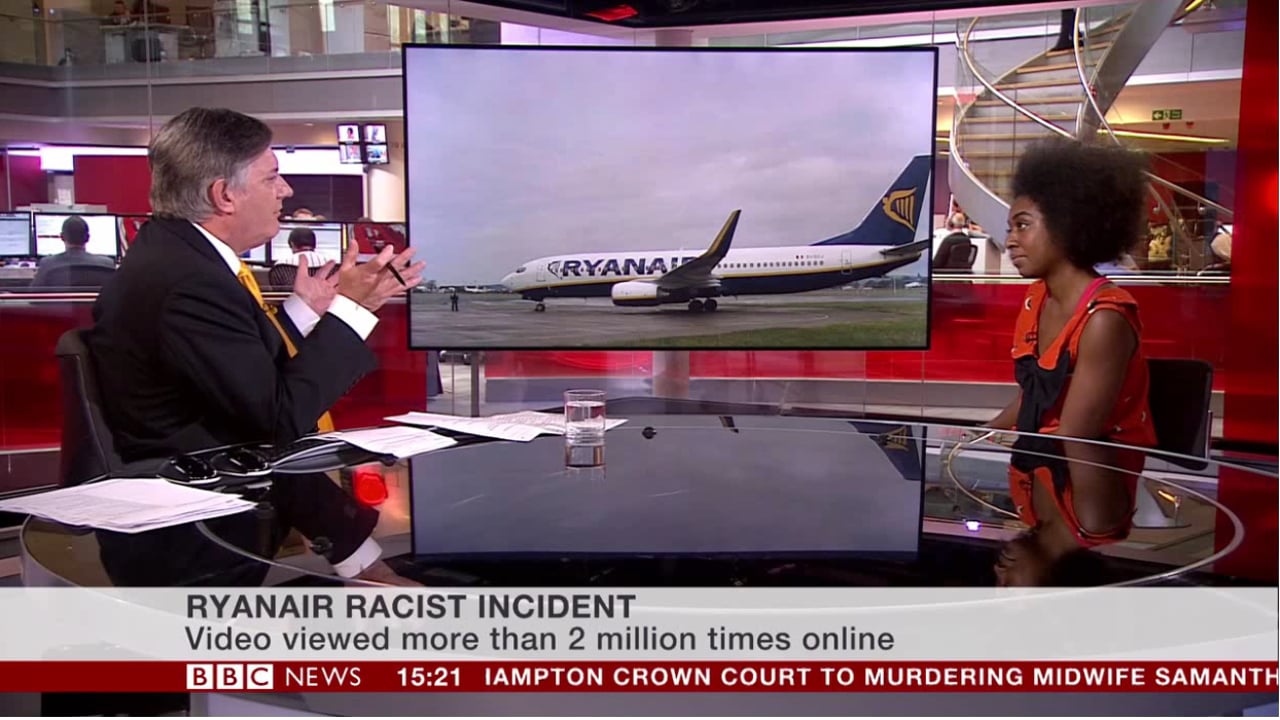

It is unsurprising that online spaces are frequently the site of such negative interactions. Social and political control of women, especially women of colour, is manifested in everyday experiences, and this is due to wider structures of inequality and oppression. For example, women of colour often experience sexism, racism and homophobia simultaneously, particularly when rebuffing unwanted sexual advances or catcalling.

This brand of toxic masculinity is both damaging to the men who uphold such bullshit concepts, as well as the women being policed or sexualised, obviously. Men are impacted by rigid ideas of masculinity which dictate what emotions they can and can’t experience and how they’re supposed experience them – which research has suggested could be to blame for increasing rates of depression and suicide in men.

Diversion from the norm in most cases results in social stigma, shame and ostracisation. And in a patriarchal society where men have a certain amount of privilege in relation to women, upholding these norms works to maintain this privilege. This in turn preserves and protects patriarchy, constructing gendered norms as indisputable characteristics through essentialism and biological determinism – which asserts that gendered differences are innate or “natural” and predetermined by biological attributes.

Systematic oppression is manifested in daily interactions on a micro basis; through outright intentional policing of women’s bodies and behaviour, as well as micro-aggressions and ‘common sense’ norms. Patriarchal privilege means that men feel entitled about sharing their so-called wisdom about the ‘proper conduct’ of a ‘respectable’ woman. What it means to be ‘ladylike’ for example. Or what clothes are considered to represent sexual promiscuity, as well as the racialised sexual stereotypes pinned on women around these men – be it on your timeline, shouted from a car window, or wherever else.

“What is significant is the way in which women are harassed online; as it emulates the forms of gendered and racialised sexual harassment and violence that occurs in offline contexts”

Most people have experienced some sort of harassment or abuse online, and trolling is now an almost inevitable experience for anybody using online platforms. There are various debates around the “causes” of trolling; including assumptions about perpetrators and the impact of anonymity, but in actuality trolling as a behaviour is nothing new. A 2014 Pew Research Centre study suggested that although men actually experience higher levels of online harassment, women are more likely to experience severe forms of online abuse such as sexual harassment and stalking. What is significant is the way in which women are harassed online; as it emulates the forms of gendered and racialised sexual harassment and violence that occurs in offline contexts, but at what appears to be a heightened level.

Not only do these platforms provide yet another means of policing, harassing and silencing women, but these behaviours seem to be disproportionately higher online. Or perhaps it just seems that way because it’s concentrated on our timelines, rather than in disconnected incidents in offline settings. It could be that the medium of social media provides such an effective platform for harassment that it actually encourages this behaviour and thus perpetuates it.

For this reason, I am drawn to the idea of “safe spaces” as a temporary respite from this. By safe spaces, I mean informal or formal groups in either online or offline contexts which encourage and promote understanding of commonalities as well as difference. This may sound overly vague or utopian, but in setting the parameters of spaces so that they resist the hegemony of ordinary day-to-day settings you can at least attempt to alleviate the impact of said hegemonic structures, albeit briefly.

Connecting with people who have shared experiences can be a lifeline, particularly for minority groups. As a woman of colour, I find it intensely validating and enriching to speak to people who already understand the multiple axes of oppression that influence our daily lives. It can be exhausting having to explain this to people who do not share this experience. Safe spaces can play an important role in protecting yourself momentarily from all the bullshit that happens both online and irl – and this is why it hurts so much when these spaces are invaded. White, cis, hetero men: you literally hold dominance over most forums, leave us the fuck alone.

The internet may be the site of a great deal of negativity, but it is also a place for creating your own platforms and spaces. I wish I had access to platforms such as gal-dem and Consented when I was growing up. It’s hard to feel at home in spaces that actively reject you, but a sense of belonging can arise from making connections in spaces where hegemony is actively resisted. In conclusion: home is where the white-supremacist capitalist ableist cisnormative hetero-patriarchy isn’t.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?