Artist spotlight: Heather Agyepong shines a light on Victorian black women

Kuba Shand Baptiste

02 Oct 2016

The ongoing quest for visibility has been the bane of women of colour for centuries, a feat held back by revisionist history, eurocentrism and racism. In Britain, where the art of paving over unfavourable relics of the past has been perfected, it’s not hard to imagine the sheer volume of figures of colour who remain unknown to the vast majority of us.

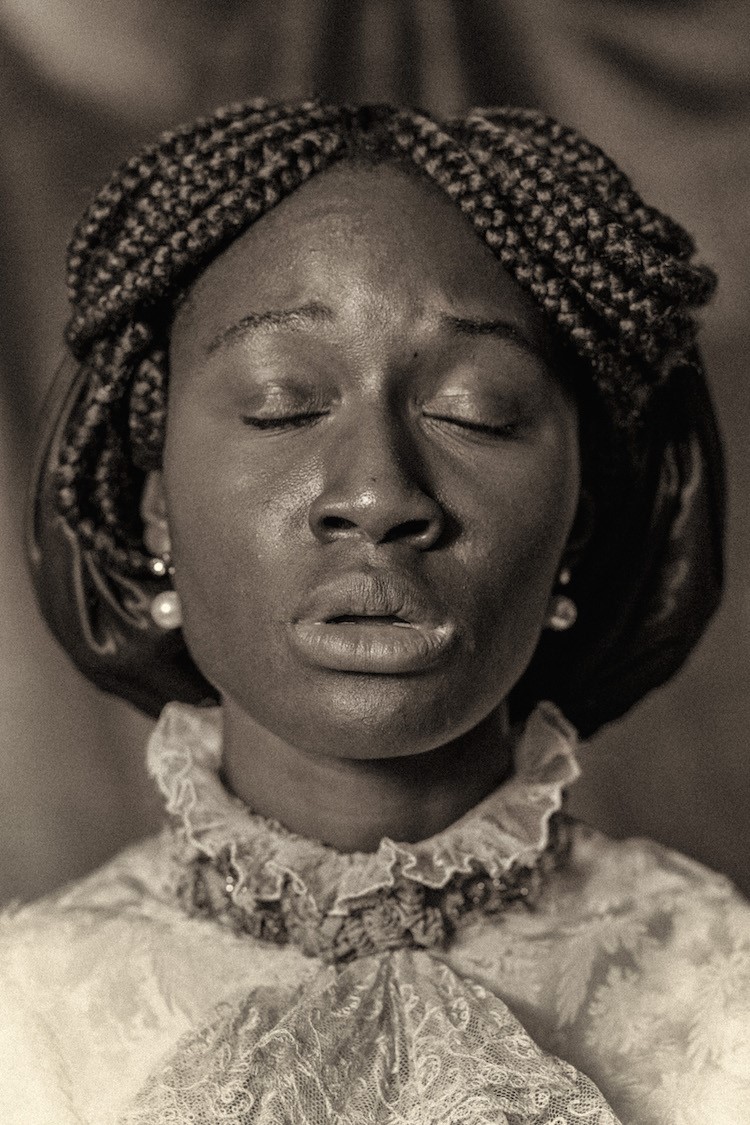

Too Many Blackamoors, one of the exhibitions featured at the Seen Fifteen Gallery’s Art Licks Weekend, works to undo that. In Heather Agyepong’s photo series, which was commissioned by Autograph ABP and funded by The Heritage Lottery Fund for The Missing Chapter project, the life of the little known west African godchild of Queen Victoria, Sarah Forbes Bonetta, is explored through a collection of reimagined portraits featuring the artist herself.

Mentored by photographer Angela Dennis during the session, Heather has produced portraits which reveal the complexities of the life of Bonetta, the orphaned slave of King Ghezo of Dahomey (now Benin), who was supposedly rescued by British naval officer, Frederick E. Forbes during an abolitionist quest around West Africa, and presented to Queen Victoria as a gift in 1850.

“I just thought the story was so unusual [and that] people should be talking about it”, says Heather, who admits that she spent much of her life believing that black people had only arrived in Britain with the Windrush generation, as opposed to centuries ago.

“Being a part of the diaspora is really awkward, because you’re like, where do I actually fit in? So I felt like [Bonetta] had similarities with questions I was thinking about,” she continues. Heather’s intrigue was also partially sparked by some of the more questionable aspects of Bonetta’s story.

“What I’ve read from my research, is that captain Forbes went over to Dahomey to talk to the king and negotiate about slavery…but what rubbish is that? The ‘abolitionist’ coming in to save the day just as she was about to be sacrificed?” Heather poses the notion that perhaps Forbes may have been motivated by something more sinister, rather than out of the goodness of his heart, a fact we can only speculate over.

Heather, who is of Ghanaian heritage, has explored themes of identity in a number of her pieces, with Too Many Blackamoors being her first foray into portrait photography. Modelled on carte-de-visite images taken of Bonetta in her wedding dress following her reluctant, royal-sanctioned marriage to a Yoruba merchant 15 years her senior in 1862, the series sees a similarly dressed Heather expand on Bonetta’s arguably grave demeanour in the original photograph, to reveal the pain and anxieties of modern black women today.

Mentioning the tendency to overlook black trauma, especially where black women are concerned, Heather highlights the fact that Bonetta’s emotional state is curiously absent from narratives about her life. “I think for me, Sarah represents [black women] now. Like, you go through a lot of trauma and crap, but you’re ‘okay’ – no one questions how you’re feeling mentally.”

She continues, “Nothing about [Bonetta’s] mental state is ever mentioned. She was married off, she was taken here, and she was very much used as an object. She’s the fantasy of the black woman, this person who doesn’t bleed, and the media perpetuates that. How Sarah is presented in documentaries is exactly the same way they present black women today. It’s that same one-dimensional portrayal.”

Speaking of the personal experiences that informed her photographs, one of which shows a reimagined Bonetta gazing into a reflectionless compact mirror, Heather goes on to expand on the nonchalance that often accompanies black womens’ expressions of pain.

“A really close friend was murdered, and when I went through mental health issues [as a result of that], no one at work believed that anything was wrong with me, people just assumed I was fine. People don’t even realise that they’re doing it, but they assume that black women are superhuman,” she says.

Accompanying the photographs at the exhibition, is a modest table and chair set, complete with a copy of W.D Myers’ At Her Majesty’s Request: An African Princess in Victorian England, two roses in a vase and a pair of modern headphones which, when put on, play a series of women’s accounts of harassment during trips abroad.

When asked about the audio, Heather, whose candy red jumpsuit and black and grey crochet twists stand in stark contrast to her likeness behind her while we talk, explains that it is inspired by conversations she had with friends about her own experiences of racism while travelling.

“I really want us to talk, not just me. I want people to understand that a lot of other people feel this way, so they can share with each other. That was the main incentive. It’s not just what I’m saying, it’s what other women are saying – are there similarities? Are there differences? And what does that mean?” she says, as if she’s considering the question as we speak.

Throughout our conversation, Heather relays her answers in a similar tone, as full of fervour and knowledge as they are of contemplation, which is the exact effect her photographs inspire in me when I look at them. One of the photographs depicts a disapproving Heather-as-Bonetta scoffing at kente cloth draped over a chair, which Heather explains represents the “internal conflict” between the new and the native homes of black diasporans.

I ask about another photo, a striking image of Heather mid-sigh, or cry (it is open to interpretation, after all), and she hesitates ever so slightly before answering. “It took around six to eight hours to do”, she says. “Photographer Angela Dennis was mentoring me during the session and she was hurling abuse at me because I really wanted to really re-enact what I was going through. She said things that I internalised at the time, over and over again. Things like: ‘why are you looking at me?’ and ‘stop looking at my hair’.

“I wanted it to be as truthful as I possibly could. It was a really draining session and I think that that was just a moment both of release and of feeling like I’d had enough, because there were so many moments where I’d be walking around and someone would say something crazy to me, and I’d have to stop, breathe and take a moment to compose myself.

“Sometimes when I’m talking to my mum about [painful] things from the past, there will be a moment when she starts talking about a trauma that’s happened, and then she’ll come back from it suddenly. So I wanted to capture those little glimmers of truth,” she says.

And she has. Having moved away from the tale that many have come to regurgitate and inserting herself into it, Heather’s photography affords Bonetta the agency that she was stripped of throughout her life.

Art Licks Weekend is on at the Bussey Building from 29th Sept-2nd October