Should we be relieved that grime has gained recognition at the Mercury Prize nominations?

Chanté Joseph

12 Aug 2016

This week nominations for the Mercury Prize were announced, and, despite viral campaigns highlighting the lack of diversity generally seen at awards ceremonies (remember #OscarsSoWhite?), yet again the Mercury Prize has failed to measure up.

The Mercury Prize is a prestigious award that promotes and recognises the best in UK and Irish music. The prize itself recognises the album of the year. Like most awards, the Mercury Prize is problematic on several levels. First of all, the 2016 judging panel is a problem. This year we see two people of colour out of twelve judges deciding on “the music equivalent to the Booker Prize for literature and the Turner Prize for art”. While ethnic minorities in the UK only make up 14 percent of the population, I believe that we need more representation on voting panels because of the debt British owes to our culture.

And, though the Mercury Prize is very popular, it is seen as both a blessing and a curse on the artists who receive nominations. When Elbow won the award in 2008 they saw a 700 percent rise in the sales of their album, but when Dizzee Rascal won his Mercury Prize in 2003, the media attention wavered and he ended up collaborating with Robbie Williams, arguably in an effort to gain mainstream recognition. Clearly post-success, these awards only count if you belong to a predominantly white genre.

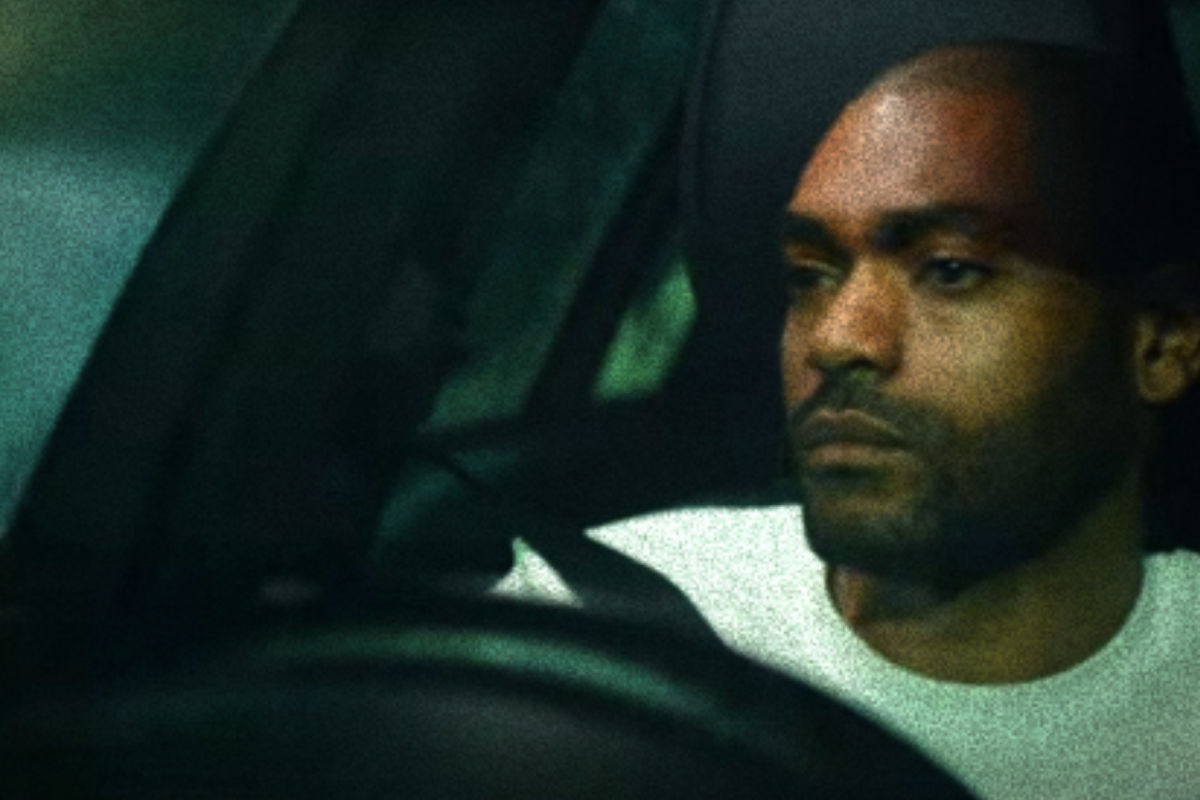

This year, a massive intake of black artists have been nominated for the prize, including Laura Mvula, Michael Kiwanuka, Skepta and Kano. The most interesting on this list are of course both Skepta and Kano: two longstanding grime artists who have been leading the scene since the early 2000s. To have them nominated in the same year is excellent, but we have to consider at what cost their nominations have come, and why they have been nominated in the first place.

The new found obsession with grime by white people means that they can have the black British working-class experience through interaction with the music without actually having to acknowledge the struggles and the tribulation that the music and experience is born. They are able to view it from a place of comfort and palatability.

To delve deeper, grime music – despite grime DJ Logan Sama’s vacuous comments – is an art form created by working-class black Britain. The experience grime describes is the black-British working-class experience, and it is important to note that white and black experiences of the working-class struggle are distinctively different because race is a social identity that alters the way you experience life. One of bi-products of grime becoming such a popular and well-respected art form is that everyone wants to see themselves in the sub-culture that surrounds it, so they feel closer to it. This results in its origins and its messages being watered down. Now any discussion on grime by well-respected writers is one that completely ignores race as a factor of its origin.

This harks back to the age old idea that being black is cool despite our grievances and the suffering of our people. Middle-class white kids can take off their tracksuits and take off the accents when they’re tired of wearing our culture as a costume and walk into spaces to not be harassed or deemed a threat. They continue to perpetuate a dangerous perception of black people whilst simultaneously absolving themselves from any of the negative stereotypes attached to the culture. I see it as the equivalent of poverty porn and it’s disgusting.

The music and the experience of grime is being bastardised by middle-class white people, those who shamelessly send Stormzy racial slurs on Twitter, whilst claiming the music and culture as their own. Speaking to 19-year-old DJ and producer, Selecta Suave, who has a flare for grime and eclectic sounds he explains that, “There is so much more to grime then some tracksuits and a couple of lyrics from six months ago… C’mon bruv.” His anger came from attending the popular club night, Eskimo Dance and hearing the classic Dizzee Rascal song ‘Stop Dat’. The room full of white boys could not utter one lyric to the song. He asked, “Are you Stormzy fans or are you grime fans?”

I do acknowledge that this is an incredible achievement for artists who were once perceived as underground to now be taking up very open and predominantly white spaces. And yes, we all hope that soon these awards will continue to respect and recognise it as a legitimate genre. Wiley put it perfectly “Brits ain’t letting dons in there like that” when talking about how Kanye brought 40 grime artists on the stage at the Brits. The problem is that these British awards really do not want much to do with us at all, which means their award shows stay “embarrassingly white”.

Despite all of this, it was argued by Prowse in her gal-dem piece about the history of award shows that the very idea of these awards are inherently colonialist and will never serve to uplift those who are a by-product of the empire but just remind them of what they are and that is “Other”. We see this bias in the way award organisers fail invite grime artists to perform at their prestigious events. It seems that the only way for a foot in is if you tailgate behind an American star.

As grime is an autonomous black artform, it should be recognised as just that. The fact we celebrate the rarity of not only black grime artist but black artists in general goes to show that we are indeed the Other. Why do we want to assimilate into the same structures that do not want us to succeed? Both Skepta and Kano should boycott the Mercury Prize and host a massive shubz; their work deserves to be celebrated and appreciate by those who truly love the movement. Whatever the outcome next month, the Mercury Prize does not legitimise their music, the people, the culture or the black working-class struggle their music was born from. We don’t need affirmation from your white-washed colonial award ceremonies.