Grenfell: ‘When the charities go away and the media goes away, who is left?’

Nabihah Parkar

14 Jun 2018

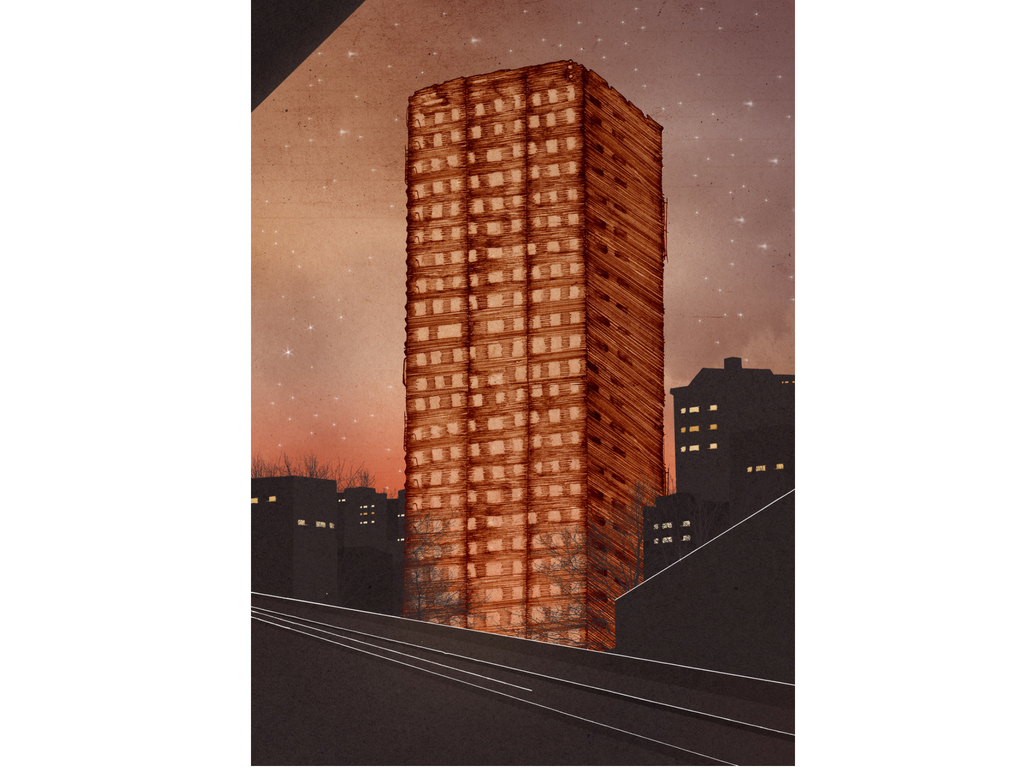

Illustration by Charlotte Edey

Afterwards, people felt empty. They had lost their friends, they had lost their families, and they had lost the familiarity of home. Images of the blaze lit up television screens and were plastered on social media during the early hours of the morning on Wednesday, 14 June. Everyone would remember the name of the tower – Grenfell has now become a part of our history.

Tensions between the local community and the authorities responsible for maintaining their wellbeing were rising; the EU referendum had come and gone; the general election had come and gone. And although the fire in west London came, the memories of those who disappeared with it, as well as the efforts of those who battle injustice in their names, refused to just “go”. Families from the Caribbean, Morocco, Afghanistan and many more continue to stand their ground. They want answers to their questions, funerals for their lost loved ones, and houses to rebuild their lives – yet many have been left waiting.

The context and circumstances may have changed, but feelings of anger and frustration from local communities towards the government have not. Khalid, 21, from White City, has friends in the area as well as family members who know people from the tenth floor that managed to escape. He explains that emotions felt by the community of west London are nothing new in the aftermath of the Grenfell fire. “The feeling they have toward the government is not a new feeling,” he says. “What people are feeling now is abandonment. They were feeling it already but now there is a total lack of faith.”

“They want answers to their questions, funerals for their lost loved ones, and houses to rebuild their lives – yet many have been left waiting”

Khalid goes on, “At the end of the day when the charities go away and the media goes away, who is left?” There is already a sense of desertion that is being felt by the survivors and the neighbours of other tower blocks. These feelings existed before and they exist after. When Grenfell is taken out of the equation, these feelings are a common denominator among ethnic minorities.

It doesn’t matter the race, religion or nationality – in the eyes of those in power we are all the same. Grenfell serves as a painful symbol of the perceived worth of non-white majority communities in Britain. Communities comprised of different nationalities who may be searching for a better life and future for their children. Communities within which various native tongues and cultures are regularly smeared in the media. Communities who have lived here for generations but remain on the outskirts of the government’s concerns.

A volunteer from east London who gave up her job to continue helping those affected by the incident, Amina, 27, describes the build-up of widespread distrust in the local area. She says, “in the beginning, survivors didn’t trust the council. Now, it is getting to a point where they find it hard to trust anyone.

“They don’t trust any other community groups or anyone external because everybody has their own agenda. Some people are money hungry or are on a power trip.” Survivors and other community members struggle to identify the hand that is truly held out to help them in their time of need. If turning towards the local council is not an option, and there are cracks among people in surrounding communities who have used the fire for their own selfish desires, who can they trust?

“At the end of the day when the charities go away and the media goes away, who is left?”

With every day that Grenfell’s local area goes without answers as to what happened that night, the wider the circle of mistrust stretches. Khalid describes the community as “fragmented”, unable to decipher who is there to help and who is there for personal gain. Political protests were planned in the proceeding days but not to the accordance of all of those affected by the fire – the immediate response caught by the media was that of uproar.

“The residents don’t want to be a part of protests,” Amina assured – yet because of the connection drawn between political protests and the reaction of Grenfell residents, “a lot of them get abuse now; verbal, physical and online,” she says. Given the general election and mounting austerity-related issues, it’s no surprise that the political overtones of the Grenfell fire drew a response from those directly and indirectly affected by the tragedy. But many residents themselves were left divided on the timing of the protests, with many still in mourning and shock.

If the communities who are most in need of support are the ones that are being ostracised, how can Britain’s political culture claim to be inclusive? In 2017, diversity in Parliament broke records with the largest number of black, Asian and ethnic minority MPs it’s seen yet. This number was a grand total of 52 out of 650 MPs, not even making up 8% of the total number of MPs sitting in parliament. And if groups like those in west London don’t see themselves reflected proportionately in positions of power, how can they trust the diplomatic system to make decisions on their behalf? Khalid mentions, “a lot of people in this community don’t feel like they have or had a voice,” while Amina says that “it was the community who came forward in the time of need”.

“If groups like those in west London don’t see themselves reflected proportionately in positions of power, how can they trust the diplomatic system to make decisions on their behalf?”

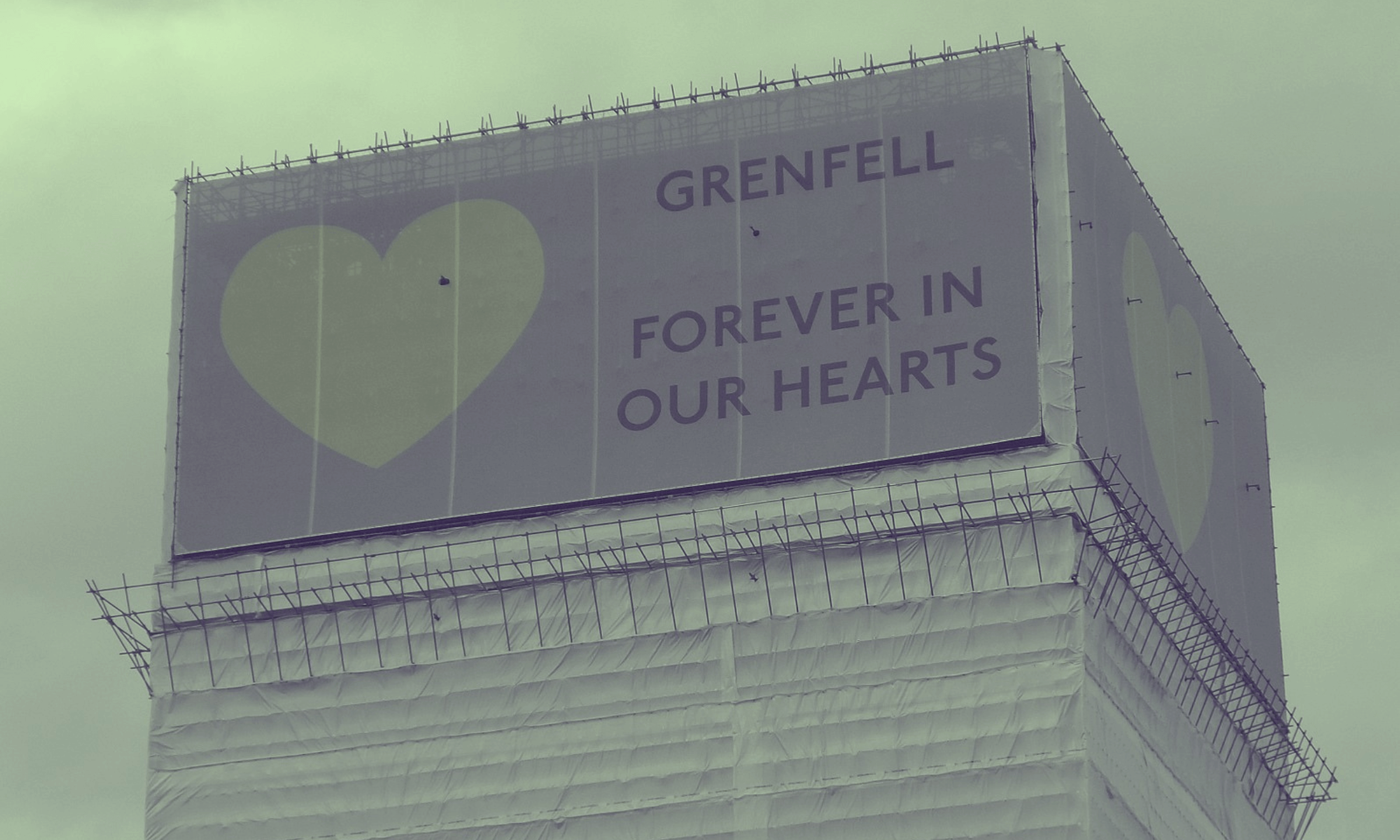

Diverse community groups who are concentrated in west London, and which the Grenfell Tower incident zoned in on, have always been critical of the government and of their local council. And the disaster, understandably, did little to restore what little faith residents had in the authorities in the first place. The tower stands as a mental and physical reminder of loss. As Khalid says, “people see that building every day. The tower is there and has been like that for months. Every time I look at it, it doesn’t get any better. It is not something I can just forget about”. It is not something anybody can forget about. But like many of those affected directly or indirectly, the only silver lining, as Amina says, would be to see those responsible “behind bars”.

We can hope for answers. We can hope for justice for the families. We can hope that a similar situation does not repeat itself. The dynamics between those with political power and ethnically diverse communities will need cooperation on both sides to build faith and trust in the relationship. It only takes one voice to speak up, but what momentum does that voice have if it is to fall on deaf ears?

From gal-dem’s print issue #2 published in September 2017