In one of the particularly devastating developments of late, it was revealed that May Brown, the leukaemia patient who launched a successful campaign against the Home Office’s rejection of her sister’s visa for a life-saving stem cell transplant, died last week.

For a short while following the reversal of the Home Office’s ruling, it would seem that the public’s efforts to make the transplant a reality (as opposed to the state) had successfully served justice for May. Here was a then twenty-one year-old, with a family and a future ahead of her, who was given renewed potential to experience a long life.

“Despite having the transplant in January after the Home Office overturned its decision, May relapsed three months later”

But despite having the transplant in January after the Home Office overturned its decision, May relapsed three months later, with doctors reportedly informing the twenty-four year-old that little could be done to reverse the situation. She died surrounded by those she was close to, including her husband Mike.

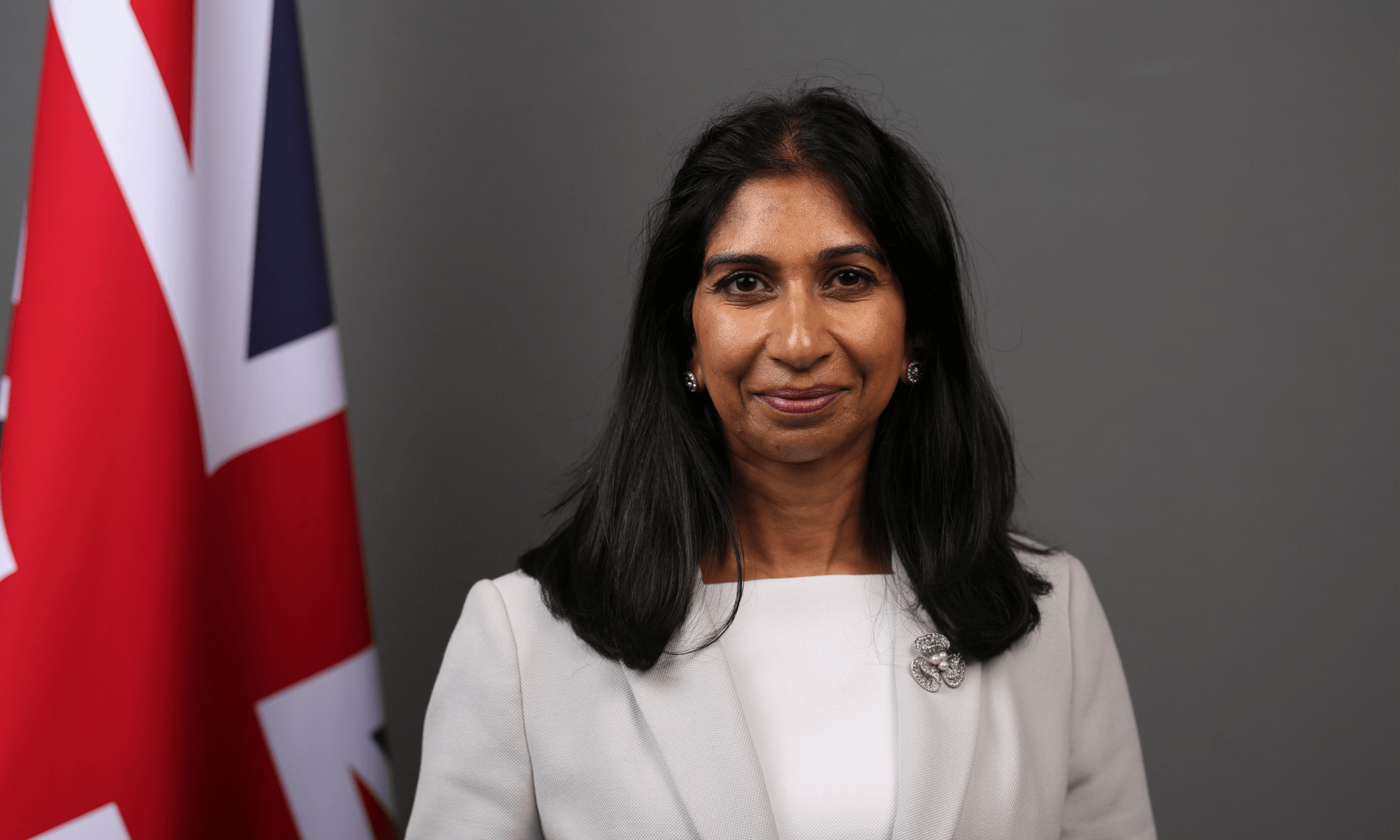

The Home Office originally denied UK entry to May’s sister and Nigerian citizen, Martha Brown, on the basis that her £222 a month salary did not meet entry requirements. Rigorous campaigning from the likes of May and the African Caribbean Leukaemia Trust (ACLT), saw the launch of a Change.org petition, which reached 60,931 signatures before the department went back on its decision.

As horrible as the reality is however, cases like these are not uncommon. Excluding the specifics of what happened to May, stories of the Home Office’s tendency to negate the importance of the lives of immigrants, as well as their relatives, have run rampant for years.

Theresa May’s tenure as home secretary – along with Amber Rudd’s, her successor – has, among other atrocities, seen mothers who have lived here for almost 30 years torn from their families, and secret charter flights attempt to quietly return immigrants to their birth countries, regardless of the dangers that await them. Yet, this increasingly cold and unforgiving approach to dealing with people whose presence could save the lives of others as well as their own, doesn’t seem to be on the way out.

“Patients from a black, Asian or ethnic minority background have a 20% chance of finding the ‘best possible match from a stranger’, compared to 60% for white people“

In a similar turn of events to May’s, college caretaker Isaac Aganozor, who also has leukaemia, launched an appeal last year for his brother, Patrick, to come to the UK from Nigeria in order to have a bone marrow transplant. Unsurprisingly, Patrick, who makes a similarly modest living in Nigeria to May’s sister, was denied a visa in April last year. This is in the face of the fact that the brothers are a 50% match, making Patrick Isaac’s “only available matching donor”, according to specialists at St Bartholomew’s hospital in London.

Finding a match for people with blood cancer is an already difficult task. According to blood cancer charity Anthony Nolan, patients from a black, Asian or ethnic minority background have a 20% chance of finding the “best possible match from a stranger”, compared to 60% for white people.

Decisions made by the government, with regards to May and Isaac, speak volumes about its lack of understanding and compassion when it comes to the difficulties that people of colour face in trying to secure effective treatment for blood cancer. But, it doesn’t mean that we should fall into inaction. 60,000 people helped to prolong May’s life. We the people, PoC in particular, can do the same for others in situations like hers, whether that involves campaigning against these injustices, registering to become a donor, or both.