We need to resist the good versus bad immigrant rhetoric around the Windrush scandal

Charlie Brinkhurst Cuff

04 May 2018

Amber Rudd’s resignation late on Sunday evening might please but not placate those affected by the Windrush scandal. Thanks to the actions of her Home Office (two years after the publication of Nikesh Shukla’s seminal anthology book, The Good Immigrant), the spectre of the “acceptable” migrant has risen up like a ghost out of the waters of the Atlantic in the thrice, and now sometimes quadruple-displaced figures of black women and men who have paid the price of Britain’s greed since the times of the slave trade.

We have accepted, both societally and in the media, that the Windrush Generation – the influx of immigrants that came to the UK from the Caribbean Commonwealth countries in the mid-20th century – have been wronged. Although it hasn’t always been the case, factors in their favour are that they were invited to this country decades ago, despite Clement Atlee trying to divert the Windrush, and have arguably “assimilated”; they helped rebuild infrastructure post-war; they suffered unforgivable racism in the “No Black, No Dogs, No Irish” era and in the aftermath of Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood’ speech; most view or viewed themselves as British and, importantly, they speak English.

But the level of care and interest that their cases are currently being handled with by the Home Office seems unlikely to last, and compensation for those who have had their lives irredeemably changed – losing employment, missing mother’s funerals and being sent “back” to a country they barely knew – seems far off. Meanwhile, as they experience temporary sympathy in the problematic limelight of their “good immigrant” status, other migrants in this country are still being cruelly forcibly deported under the government’s hostile environment policy – a reminder that their fate as migrants can be transient.

“The spectre of the ‘acceptable’ migrant has risen up like a ghost out of the waters of the Atlantic in the thrice”

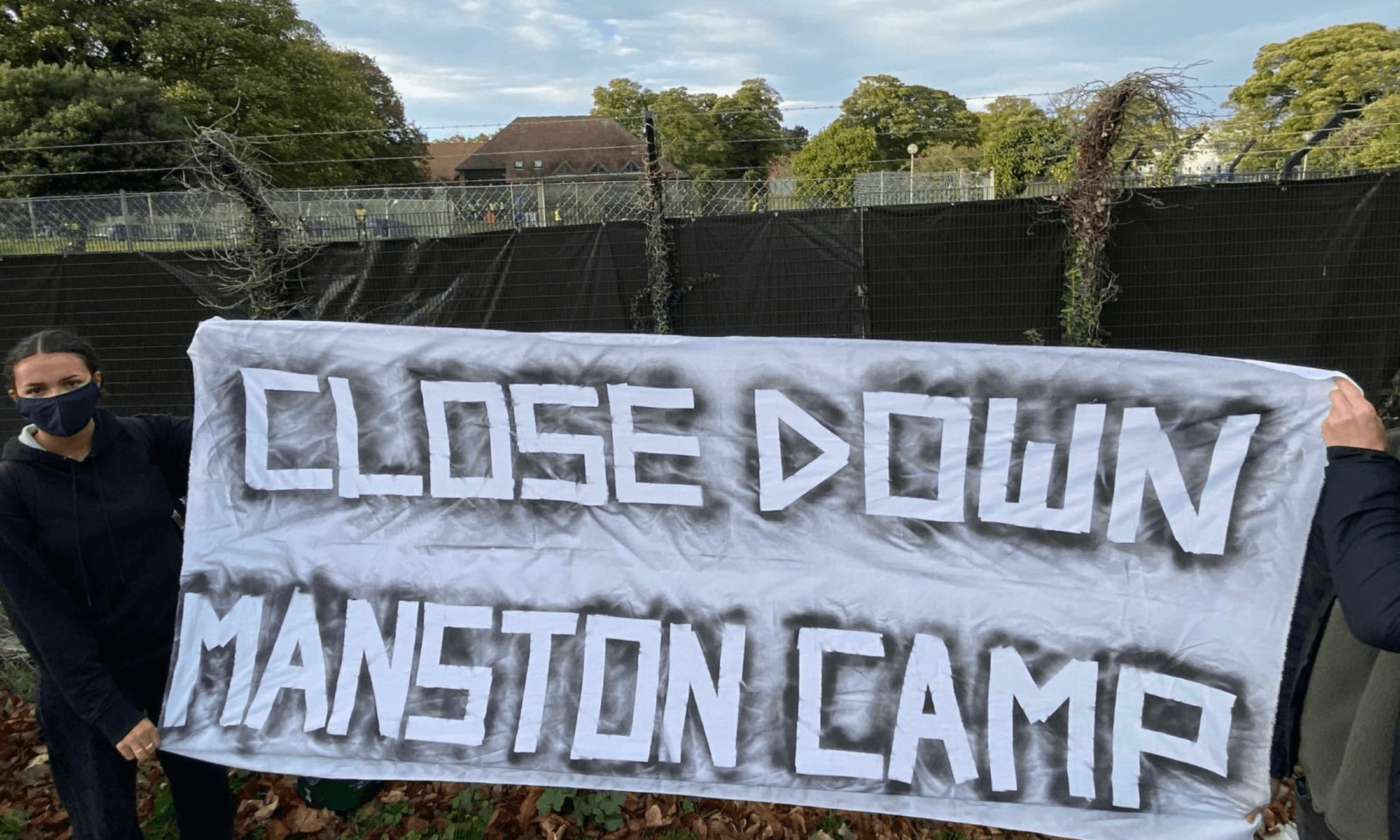

Since the beginning of this year, Yarl’s Wood immigration removal centre has been a bubbling haven of activism. The centre is infamous for its indefinite detention of women who sit in a terrifying limbo, kept in prison-like conditions, moments away from being deported, but more often actually being released into the community in a perverse act that does nothing to help justify their detention in the first place. It’s not the only one of its kind in the UK, but it is the most notorious. In February, as many as 120 women detained at the centre went on hunger strike to protest the issues they said they were facing – from the “detention of people who came to the UK as children” to “systematic torture” and “discontinuing hormone treatment” for trans detainees.

But sadly, many of the women who joined the hunger strike were told that their cases could be accelerated. “The fact that you are currently refusing food and/or fluid: may, in fact, lead to your case being accelerated and your removal from the UK taking place sooner,” read a letter they received. Just last week a transgender woman in Yarl’s Wood who reported being sex trafficked by a gang into the UK was deported to Thailand to a “situation of great danger”. Known as Tanya, the woman was part of the hunger strike and has faced solitary confinement and mental health problems as she fought to stay in the UK.

Even amongst more recent Caribbean migrants there are awful tales of mistreatment. Shankea Stewart, who was sent to the UK from the Caribbean as a young child to live with her dad, doesn’t quite make the cut. She has been denied leave to remain, couldn’t take up offers at university or work, and missed her own mother’s funeral in Jamaica because the Home Office want to deport her. She is not covered by Amber Rudd’s Windrush reforms because she is of the “wrong” generation.

“Other migrants in this country are still being cruelly forcibly deported under the government’s hostile environment policy”

“The title the Windrush (generation) got as the ‘good immigrant’ was only given to them because of political agendas,” she tells me. “They don’t want the public to know that the ‘bad immigrant,’ like me, actually have a story and suffer unfairly. They don’t want the public to know about the horrendous fees that ‘bad immigrants’ have to pay. They do not want the public to know about the mental abuse they face from the border force.”

This of course, is beyond government policy. On a Channel 4 news special exploring the Windrush generation scandal last week, racist author David Goodhart (who is invested in white “self-interest”), dominated the conversation by attempting to hammer home the point that most people in the UK do not like immigration. On that, and that alone, we agree. I do not doubt that women like Tanya and Shankea are not the type of migrants he, the government, or the right-leaning public would naturally feel any compassion for because due to their undocumented status they have been dehumanised. The danger of institutional and societal racism and xenophobia isn’t convenient for them to recognise.

“Our sense of humanity must stretch further to overcome the worrying dichotomy of narratives between good and bad immigrants”

Even as the country and national media bands together to support the Windrush generation, our sense of humanity must stretch further to overcome the worrying dichotomy of narratives between good and bad immigrants; between those with heartbreaking stories like Tanya and Shankea’s and those without. The point is that the UK, as one of the richest nations on earth and responsible for the destruction and subjugation of some of the poorest, should do much much better when it comes to recognising the humanity of those who reach our shores.