Winner of the BAFTA Award for Best Documentary, and nominated for an Academy Award in the same category, Ava DuVernay’s 13th provides a timely and solemn reflection on the legacy of slavery in the United States. The fallouts from this legacy have manifested themselves in the Prison-Industrial Complex of the last half-century. The Prison-Industrial Complex (PIC) is a social phenomenon described as “the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems.”13th makes the argument that although the PIC as we know it today gained traction in the 1970s and 80s, its roots can be traced to as far back as the abolition of slavery in the United States in 1865.

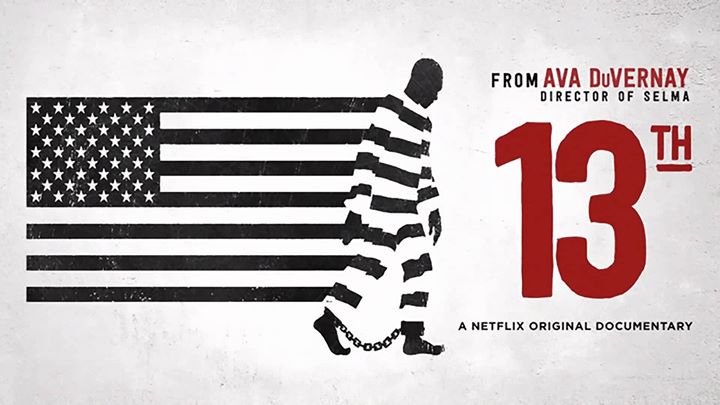

Taking its name from the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution that formally abolished slavery, the crux of the documentary’s claim lies in the fact that the methodical wording of the constitution provided a loophole for White slave owners. Namely, that they could continue their exploitation of Black labour well after their freedom was granted. The Amendment states that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” It was through this semantic particularity that many emancipated African-Americans found themselves returned to the shackles of slavery.

The documentary opens with the voice of former U.S. President Barack Obama at the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People) National Convention in 2015, where he proclaims that the United States is home to 5% of the world’s population, but 25% of the world’s prisoners. The galling disparity in these statistics provide the backdrop to the documentary as the calculated, politicised and monetised criminalisation of communities of colour- particularly Black communities – is explored. The scope of 13th is expansive, taking the viewers on a journey from the abolition of slavery in the late 19th century up to the present day. It is punctuated by archival video and photographs throughout, as well as interviews with prominent African-American writers, educators, and activists. They include professor and historian Henry Louis Gates Jr., commentator Van Jones, educator and author of ‘The New Jim Crow’ Michelle Alexander, and activist Angela Davis. The most visually captivating aspect of the documentary is in the way that it seamlessly blends infographics, music, lyrics, and video footage with the running commentary of the interviewees. The documentary is masterfully edited by Spencer Averick , with the chronological narrative flowing so effortlessly that the interviewees often finish each other’s sentences despite being filmed in different locations. This gives 13th a quality similar to that of an ongoing discussion, removing the audience from their role as merely the viewers to that of participators. Despite the occasionally historical nature of the documentary, there is an urgency to 13th that gives it relevancy – pictures of Black chain gangs in the early 20th century are juxtaposed with images of Black men locked in chains in modern prisons, and the militarisation of the police force is represented in almost identical photographs from protests in the Jim Crow south and Black Lives Matter rallies.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V66F3WU2CKk

13th also displays the parallels between Donald Trump’s recent presidential campaign with the campaigns of former U.S. presidents including Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton, in the way that they appeal to the White working class electorate;fanning the flames of their paranoia. The maintenance of law and order has been a painstakingly crucial ingredient to electoral success in the United States since Nixon’s campaign in the 1970s, and this tactic has proven deadly for many Black communities. By playing into the hands of the stereotypes of Black men as brutish, animalistic rapists, first depicted in D.W. Griffith’s ‘Birth of a Nation’, these politicians were able to turn White hysteria into ballot results. However, 100 years on, the depiction of black men in ‘Birth of a Nation’ rings uncomfortably true to the political climate of today, inundated by internet trolls, rising Nazi appreciation in the form of the ‘alt-right’, and a cancerous growth of fascist sentiments sweeping over Europe and the United States.

13th is a riveting documentary, and a stark reminder of the ways in which Black bodies have been exploited and abused for profit. By shedding light on the complexities of the PIC in a way that is digestible, the documentary gives the viewer the tools and information needed to make the link between the United States’ legacy of slavery and the protests breaking out all over the country today. It is a perfectly articulate rebuttal to those who shoot down Black people’s complaints with sighs of‘slavery happened hundreds of years ago, get over it!’. DuVernay crafts a felicitous juggernaut of a documentary feature that doesn’t get caught up in the convoluted details of politics and public policy . Rather, it provides a concise and powerful message of why we should absolutely not get over slavery, and how the apparatus of slavery-era America has redefined itself as the Prison-Industrial Complex.

The most powerful scene comes towards the end of the documentary: a speech at one of Trump’s campaigns where he reminisces about the “good old days” (read: Jim Crow America) and footage of Black protesters being pushed and harassed at Trump rallies is played over grainy, archival black-and-white footage of a Black man also being aggravated by a group of White people. As the footage goes back and forth between the present day and segregation-era America, it becomes clear that not much has changed. The insistence of 13th to not sugar coat what Michelle Alexander describes as‘a genocide’ of black people in America leaves the viewer feeling enraged, hurt and with a sour taste in their mouth, but isn’t this what any good documentary should do?