“Not everyone is deserving of your kindness – some people can be let go.”

At 18, my best friend’s words were revolutionary. Never before had I considered the need to prioritise my own emotional energy before that of others. But that year I went to an elite university, and everything changed. Having always occupied fairly privileged spaces I (perhaps somewhat naively) thought that I’d seen the worst that privilege had to offer. I’d seen how callous youth or wilful ignorance could lead to harmful and obscene drinking chants such as “fuck her in a ditch/fuck her if she’s dead,” to grotesque slogans like “we’re the one percent”. I firmly believed that university would be different, and, in some ways, I was right. My university experience did lead to me meeting some of the kindest people I have ever come across, and yet I also came across swathes of negligence, and some horrifying actions which prepared me for the big, bad, “real world”. My first year of university was a baptism of fire.

Like many other women of colour, navigating that transition to university was perhaps harder than it ought to be. Adapting to life in a town which simply wasn’t as diverse as the place I’d grown up required some adjustment; however, what was more brutal was adjusting to a space that was predominantly dominated by men. Having been to a girls’ school probably also added to me feeling out of my comfort zone.

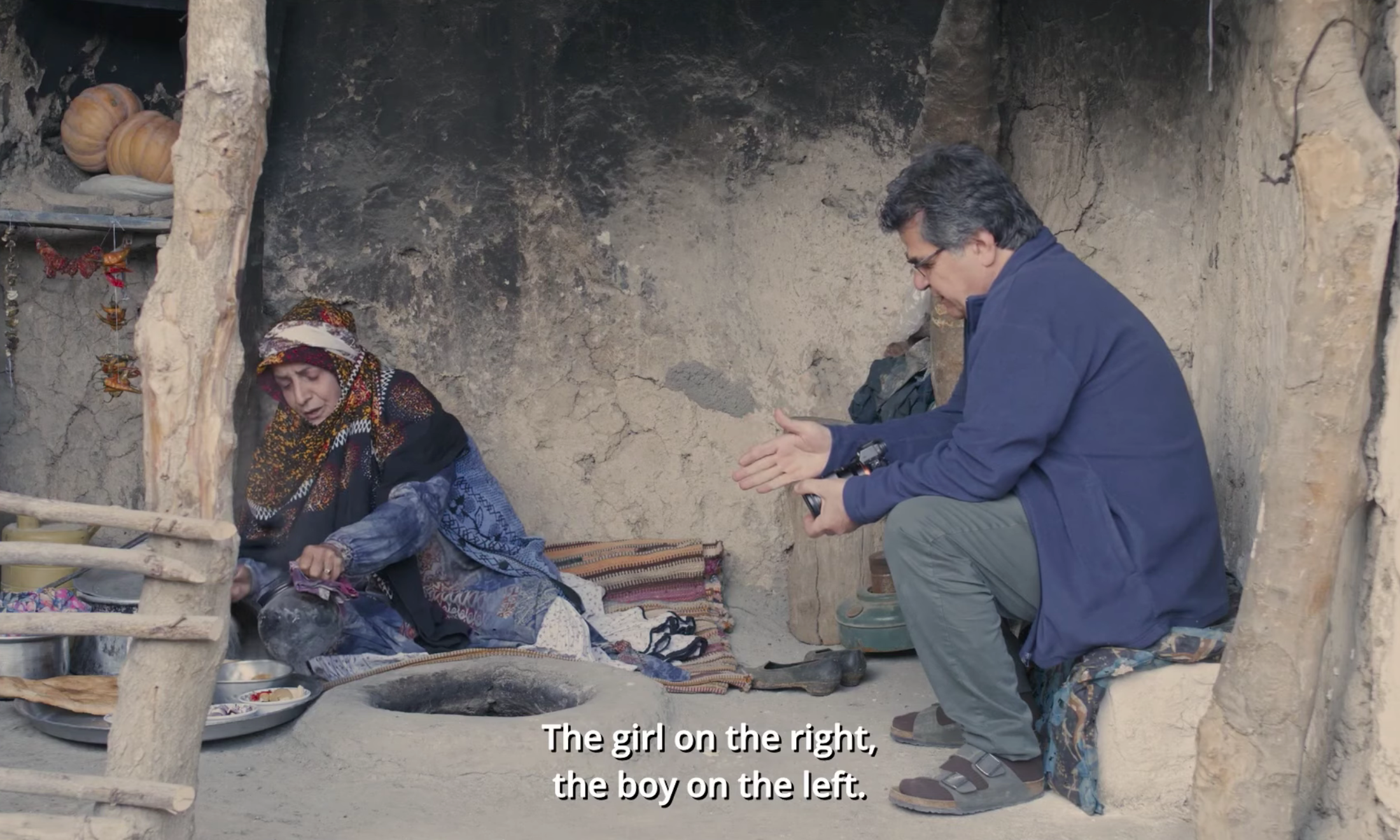

In hindsight I can recognise that my treatment was both racialised and gendered. The brief highlights involve: endless derogatory remarks, introductions to strangers where my gender and religion were flagged up (think “Osama’s daughter”, and much, much worse), tiresome pranks involving intimate items of clothing, references to camels (marks for novelty, considering I’m Muslim, and we must all hail from the Middle East), or perhaps the most difficult: persistent knocks on my bedroom door routinely every night for months on-end from a boy asking to be let in, and refusing to accept the word “no”, at least “until I gave him a real response”. Once, tear-stained, exhausted, and with many essays before me, I confronted this would-be Romeo to ask him why he kept persisting. His response: “I don’t know, I just – you don’t drink, but you’re still social. You’re still one of us. It’s like you’re a good girl, with a filthy slut inside. Man, it’s fascinating.”

These instances, these focalisations on aspects of my identity are not unique. They hint at the detachment and lack of care, the misogyny and racism that is still seething within every institution, and skim the surface of what so many other people who deviate from a supposed norm of white, cis identity have experienced. I know that I could have had it so much worse. But being repeatedly called “brownie” after I’ve reminded someone of my name multiple times or being told to “go somewhere else where there’s real lad culture, and they spray paint slut across your door” is not something that anyone should have to experience. I could also have had it so much better.

“Recognising the oppressions at play in your everyday life can be exhausting. “

It was feminist networks, and safe spaces for women of colour, that reminded me that better could and did exist. I had been convinced that going to an institution prized for intellectual rigour would mean that I would by surrounded by individuals who understood that true intelligence was emotional understanding and empathy. Realising that someone can recognise structural oppression on an academic level, but still not act against it, is a bitter pill to swallow and can be hugely demoralising. However, being surrounded by individuals who understand your experience, because they share that experience and therefore understand and share your vulnerabilities, provides an uplifting and supportive community. I am so thankful to have been brought into networks of love and solidarity that enabled me to recognise what microaggressions were, networks that gave me the terminology to recognise certain experiences as moments of gaslighting, or simply allowed me to find friends who “get it”.

Yet, I still struggle – anytime the personal and the political entangle, it becomes incredibly messy. Recognising the oppressions at play in your everyday life can be exhausting. I spent most of my first year at university exhausted because I was tired of feeling consistently enraged. Even when I had found networks of support, I was still exhausted. I felt like I was failing as a feminist because everyone else’s anger seemed to spur them on, but my anger just seemed to overwhelm me, and I could never channel it into something productive. I was terrified of losing all the bits of myself that had been soft and kind, that would previously give my time and energy to people who didn’t necessarily deserve it. I was scared that if most people didn’t “get it” they never would, and I was scared that that feeling of hopelessness would make me bitter and hardened.

Then I came across radical softness, and the notion that emotional vulnerability can be channelled as a political weapon and can be a potent form of activism in itself. Radical softness showed me that I could still prioritise caring for myself, whilst also extending that care to others. I see radical softness as a means of accepting all those bits of yourself that are vulnerable, that are too kind, too palatable, too traditionally feminine and channelling those into a force of resistance. It’s definitely not the be-all and end-all of activism, but it allows me to re-negotiate some of the tricky bits of my feminist practice, where I can understand my faith and feminism side by side. Through radical softness, I can forgive perpetrators of oppression, without forgiving the oppressive act itself.

“A little bit of kindness goes a long way”

You can have read all the feminist theory in the world: from your Irigaray to your bell hooks or even your Spivak. You can know the ins and outs of Judith Butler and be well versed in the works of Audre Lorde or Andrea Dworkin, but you will still have to determine what shape feminism takes in your own life and negotiate what your feminism looks like. This will always be an individual choice. Radical softness accepts this individuality. I know that not everyone is deserving of kindness, and that ideas of palatability have unique pressures and complexities of their own, particularly for women of colour, but a little bit of kindness goes a long way.

I wholeheartedly believe that open dialogue can pave the way to slowly dismantling the kyriarchy (that big, bad, force getting all of us down). I know that this is a burdensome task and requires much emotional labour on marginalised voices to expose themselves, but this is where art is so fabulous: you can expose yourself, but in fancy-dress, so that you don’t feel so very naked.

This is exactly what AWOMENfest is aiming to do. Our weekend festival is a smorgasbord of the arts carefully curated to generate open and frank intersectional conversations, treating complex topics with the love and respect they deserve. Nobody ever said that we can only fight back rapidly and forcefully – there is also room for a slow, steady, loving and radically soft burn to push back against all forms of oppression.

AWOMENfest is taking place at DIY Space for London, 23-25t March. To find out more, visit www.awomenfest.com (buy your tickets, and spread the word).