This week, previews for the WestEnd transfer of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s game-changing musical Hamilton have commenced after being delayed. I boarded the Hamilton bandwagon around the time when Hamilton-mania was at its peak (early 2016). Due to geographical and financial restrictions preventing me from witnessing with my own eyes Miranda and his cast make history on Broadway, I had to settle for listening to the original cast recording of the Hamilton soundtrack on Spotify. It took one listen of the album to hook me, and I swiftly took it upon myself to coax my nearest and dearest into giving the soundtrack a listen so that they too might sink to my obsessive depths.

When Hamilton-mania was at its peak it was easy for me to feed my obsession by reading endless think pieces about the significance of the musical, and watching interview clips of Miranda and the cast. All of this, plus re-listening to my favourite songs from the album, helped me deal with the sad reality that I would never be able to fully complete my experience of the soundtrack by watching the original cast on stage; all of these activities helped me deal with my FOMO (fear of missing out). Watching the original cast of a play/musical live on stage is like being someone who was there when the Berlin Wall fell, or being old enough to remember the millennium. It means beholding the birth of a zeitgeist.

One song from the album, ‘The Room Where It Happens’ sung by the ever-sublime Leslie Odom Jr, unexpectedly came to speak directly to my FOMO. In the song, Aaron Burr, who is the musical’s narrator and Alexander Hamilton’s nemesis, speculates about a closed-door deal that he was not privy to but Hamilton was involved in, which led to Washington DC becoming the national capital of the United States while New York consolidated its positon as the defacto economic capital of America. At the song’s climax, when the company repeatedly chants ‘What do you want, Burr?’ for the first time in the play Burr is unequivocal,

I

Wanna be in

The room where it happens

The room where it happens

I

Wanna be in

The room where it happens

The room where it happens…

This musical exchange, and the dramatic journey that Burr goes through in the song, uncannily articulate the unique sense of FOMO a theatre lover experiences when they find out about a great play that is beyond their reach for whatever reason, be that time (finding out about it retrospectively), geography or money. ‘The room’ of the title transcends its literal and historical signification and comes to stand for, in a metatheatrical way, Richard Rodgers Theatre, where the original Broadway run of Hamilton happened. Theatre is a notoriously transient art form. Either you were or you weren’t there for a particular play. For those in the latter category, no amount of secondhand or thirdhand accounts of the play will make up for that singular experience of being in a live theatre audience and knowing that the performance you see will only happen once exactly like the way you see it. More generally, ‘The Room Where It Happens’ works as an anthem for anyone whose experienced longing to enter a site of power where only the privileged few have access.

Theatre as an artform is inaccessible to black and brown audiences for a number of reasons. Theatre tickets are expensive, especially for popular shows. Because in the UK there is steep wealth inequality between racial groups, this leads to theatre audiences that are overwhelming white, middle aged and middle class, even when a play may be written by or about people of colour. Geography poses another barrier. The London centricity of theatre and arts funding in the UK is staggering. A 2013 study found that London gets £68.99 per person in arts money compared to £4.58 per person for the rest of England. So, low-income black and brown people who live outside of London are doubly barred from accessing theatre by both wealth inequality and regional neglect. The livestreaming of theatre performances has proved a partial solution to the geography and financial solutions. However the implications of live streaming for stage actors and live stream audiences pose existential questions for both theatre and cinema.

“Theatre as an artform is inaccessible to black and brown audiences for a number of reasons”

Parallel to the barriers against audiences of colour are the forces which work to exclude actors of colour from the stage. Most successful British actors either went to drama school or Oxbridge, or in some cases both. There’s always been a heavy expectation for young British actors to have formal training. When higher education was free and government maintenance grants were a thing, this unofficial norm was achievable for aspiring actors from low-income backgrounds. But maintenance grants are now a relic of the past and rising university tuition fees are the new normal. For those who cannot afford full-time formal training, breaking into the theatre industry is made all the more harder. When actors still somehow manage to become professional against these odds, they must then contend with a lack of plays by or about people of colour.

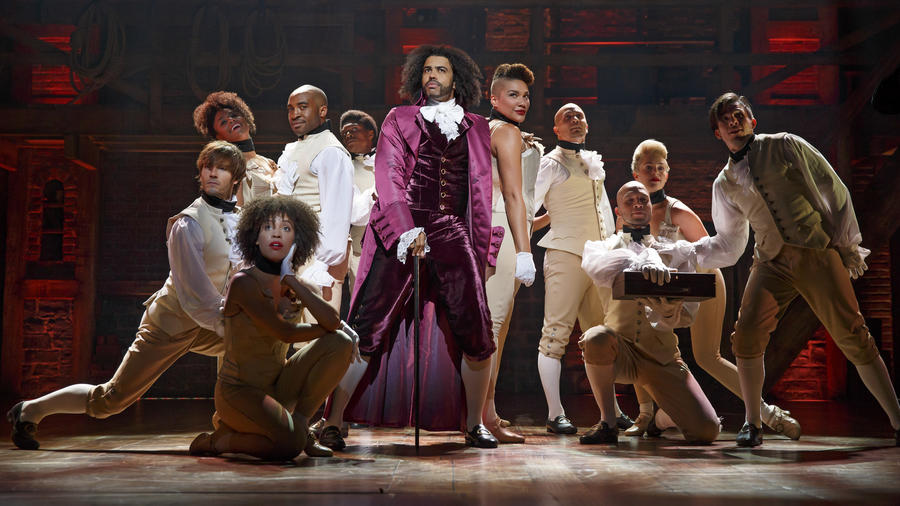

The barriers that non-white actors face when trying to make it in the theatre world were brought into focus by Hamilton and Miranda’s radical and controversial decision to cast black and Latino actors to play historically white figures. Miranda, a Hispanic-American, said that he cast the play that way to reflect America as it is today. Initially it was thrilling to read about Miranda’s majority PoC cast and see all the success the ensemble was bestowed.

“Most successful British actors either went to drama school or Oxbridge, or in some cases both”

But as my Hamilton-mania cooled off, increasingly I began to think about the historical truth of the musical. Yes, in real life Hamilton was an immigrant, but he was also a slave trader, the antithesis of the pro-abolitionist he is portrayed as in the musical. The musical’s handling of the Founding Fathers hypocrisy when it came to the humanity of slaves leaves an uncomfortable aftertaste. Equally glaring is the play’s elision of the Founding Fathers genocidal record when it came to Native Americans. From the offset I always found the musical’s over-emphasis of Hamilton’s immigrant status bemusing given that the rest of the founding fathers were also immigrants, albeit less recent ones. The African-American writer Ishmael Reed, in his vivisection of Hamilton’s race problematics, details the troubling records of individual Founding Fathers for both slavery and the Native American genocide.

Clearly from a historical viewpoint, Hamilton’s black-casting of anti-black historical figures might create a sense of unease. Yet, when you consider the history of the predominant musical genres employed in Hamilton- hip hop and R&B- then Miranda’s casting is pitch perfect. More importantly, it truly honours the founding communities of hip hop and R&B. Thus in the original casting of Hamilton, America’s national history and music history collide and conflict. Though the resulting tension between the two histories is heavy to untangle, I believe it ultimately was for to the betterment of theatre as a whole that Miranda wrote and cast Hamilton the way that he did.