‘Everybody deserves justice’: documenting the shockwaves of police violence

Jennifer Taygeta Edmunds and Sapphire McIntosh, Sapphire McIntosh and Jennifer Taygeta Edmunds

22 Jun 2018

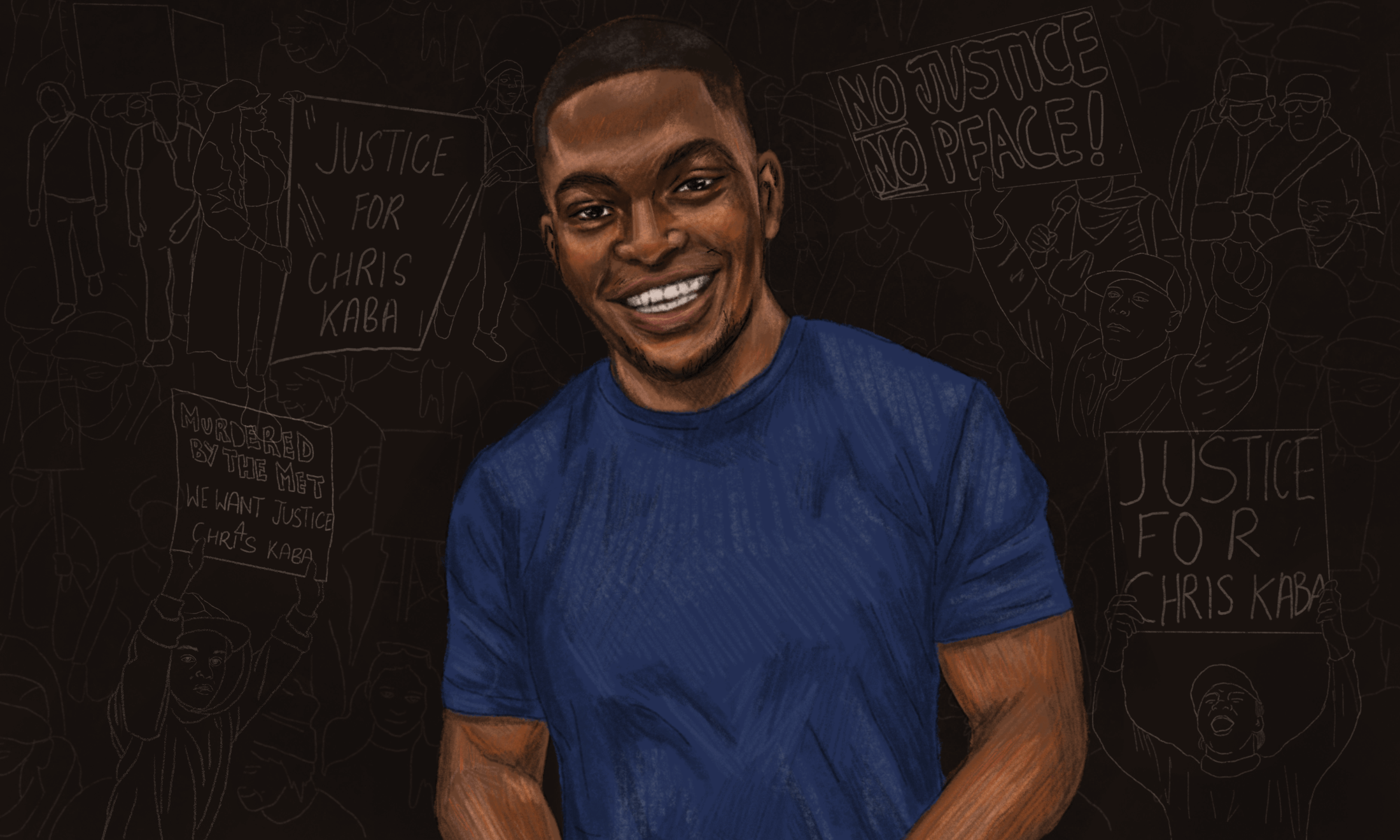

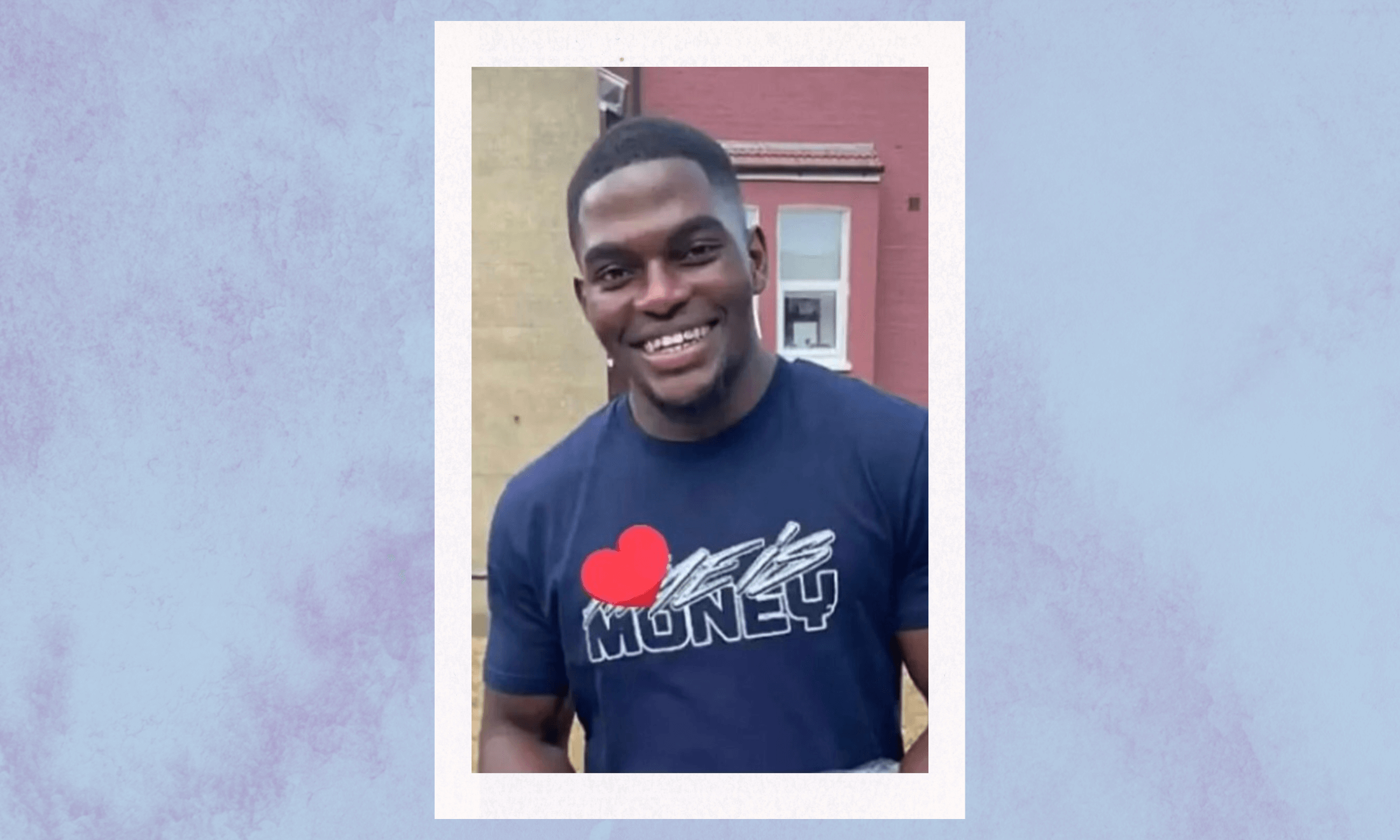

On 22 July 2017 in Hackney, young black father Rashan Charles lost his life at the hands of the police. The inquest into Rashan Charles’ death ended yesterday, with the jury concluding that the death was “accidental” and the police had employed a “justified use of force”. The coroner disallowed the conclusion of unlawful killing.

Rashan’s family (who you can follow and support on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram) have described the investigation as “flawed” and not impartial, and stated that Rashan was criminalised in court. They have nonetheless offered “due respect” to the jury, who had to “make a decision based on the limited evidence”. INQUEST notes that the context of “gangs, drugs and violence in Hackney” was highlighted to “deflect” from the police’s violent behaviour. The inquest confirmed Rashan was pursued, despite the police not having intelligence on him, simply for leaving a vehicle that was “acting strangely”.

“The footage in this film speaks to the state of racism in Britain today”

Much of the public outcry following the incident was targeted at the police brutality that led to his death, especially after graphic CCTV footage of him being restrained was leaked by friends [no direct link after jump]. However, some of the reporting around the resultant unrest in Dalston also garnered condemnation of this so-called “violence“. As the skewed narrative unfolded in mainstream media, Sapphire McIntosh, a vox pops journalist, went to Dalston to hear how people really felt. She asked local residents about the treatment of black communities and whether the “violence” was justified, with the hope that her findings would reach those were quick to conclude that the community’s anger was disproportionate. The footage was edited by Jennifer Edmunds into the film below, and also includes contextual news, and clips from the vigil and archive.

The footage in this film speaks to the state of racism in Britain today. While filming, Saph, a black British woman, felt that a lot of black people were willing to talk to her freely as they knew she would represent them fairly. However, not many white people wanted to be interviewed: some felt it wasn’t their place to have an opinion on the incident, and two white men gave a mouthful of extremities centering around the fact they thought Rashan Charles was a bad person – a similar view to that of another white man shown in the film. Views such as theirs were aided and abetted by the portrayal of Rashan’s death in mainstream media: Claire Sambrook notes leading discrepancies in reportage, especially around the package he swallowed (later revealed not to be drugs).

“the family of Rashan Charles have been measured in their public statements, simply asking the police for due process and accountability”

Manipulation and lack of transparency extended to the authorities: as the family put it, “statements suggesting that Rashan “became unwell” or that the officer was in some way ‘helping’ him are a distortion of what we can all see on screen”. Six months on, the family also list many unanswered questions, including relating to the potential falsifying of evidence, and say that the officers involved secured an anonymous “ex parte” hearing without warning. Conversely, although this shouldn’t be necessary, the family have been measured in their public statements, simply asking for due process and accountability, and requesting that the officer not be deemed “automatically guilty”.

Misreporting and bias also plagued the unrest following Rashan’s death. Protests which took place after both a first and second vigil were tarred by both heavy police presence and spurious reporting. Consequently – especially after the second, widely-reported “night of violence”, when police tipped off live media crews, according to some reports – the protests were accompanied by moral panic and branded “riots”. However, the terminology of “violence” is questionable: are fires only dangerous, rather than tactical, when set by young black boys? As eyewitness Tash Shifrin maintains, “these kids have not gone on some wild orgy of destruction… They are blockading a major road…” Police manoeuvres that visually dominated media reports conceivably also implied more violence than they mitigated: as Shifrin continues, “…maybe with the presence of riot police, they aim to create the impression of a riot”.

In our film, opinions vary. Some suggest police presence can actually be provocative: it seems inevitable that tensions will escalate when an aggressive “circus”, as Toyin Agbetu describes it, of dogs and mounted police arrive. Others found the violence positive. However, some agreed with Saph’s hope that, whenever something terrible like this happens to the black community, the reaction isn’t always violent even if people feel like reacting in such a way.

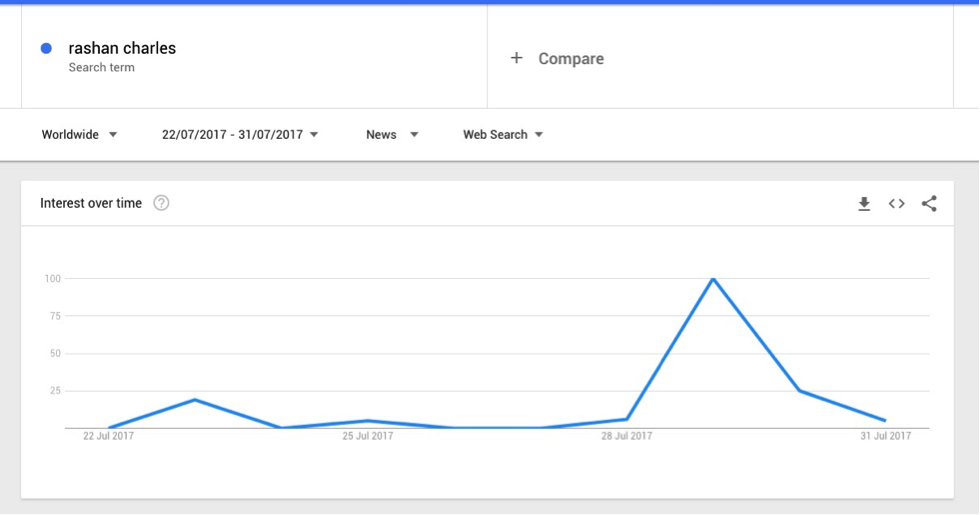

Whatever your take, it’s clear that the unrest increased media focus on Rashan’s death, as both our interviewees argued and Google Trends evidences. One reason for this delayed interest could be that while Hackney, like many London boroughs, is one of the most ethnically diverse areas in the country (just over 40% non-white), equivalent diversity isn’t reflected in journalism. Last year, Jon Snow touched on the fact that Grenfell Tower didn’t receive much attention before the fire, putting it down to the lack of a wide range of journalists from differing backgrounds. The day after the fire, hordes of white men, sweating in their suits, circled the Grenfell residents: why were they only bothered now?

Google Trends news results from the date of the first vigil, 24.07.17, to after the “night of violence”, 28.7.17, show a clear uptick for the term ‘Rashan Charles’

In our film it was important to provide context because when people of colour (PoC), especially black people, express opinions, they are often read as unjustifiably angry. The justification is partly seen in Hackney’s legacy of police brutality referenced by some of our interviewees (“Do you know how many deaths there’s been in Stokey police station?”). As Leah Cowan notes, in 1983, Colin Roach was shot dead in Stoke Newington Police Station. The inquest returned a suicide verdict, despite him being shot in the back of the head, and police came down harshly on counter-demonstrations. However, this was just one notorious case in a number of heavily racialised incidents: in the same station, Aseta Simms died under suspicious circumstances a decade before, and in 1978 stabbed teenager Michael Ferreira died after being taken for questioning instead of to hospital (a pamphlet published by the Black Unity and Freedom Party in 1972 also mentions prior unrecorded deaths in the police station, dubbed the “pigsty”). Policing practices also included unprovoked assaults, planting evidence, and targeting children.

“A third of police custody deaths in 2017 were black and minority ethnic (BME), at least a 200% over-representation”

In the 1980s, groups like Hackney Community Defence Association tackled such police crime, collecting evidence against corruption and helping press complaints to the tune of a reported £500k in victim damages. However, despite hard-won changes, racialised institutional misconduct persists. A third of police custody deaths in 2017 were black and minority ethnic (BME), at least a 200% over-representation; illustratively, the recent Angiolini Review on deaths in police custody asks, on similarities between the deaths of Roger Sylvester and Sean Rigg nine years later: “what, if any, lessons were learned…?”. Stats may even under-represent the problem: the IOPC (formerly IPCC) no longer provides ethnicity data for restraint-related deaths, official figures may underreport and accounts often go unheard because, as the London Campaign Against Police and State Violence (LCAPSV) highlights, victims of police brutality are often charged “to delay or reduce the possibility” of complaint.

“violence towards black people occurs in relation to to officers’ misperceptions that they are more dangerous or impervious to harm/pain”

The continuum of violence is especially relevant in Rashan’s case: while racial biases pervade the criminal justice system, those involving force/restraint are more glaringly anti-black. The perpetration of restraint-related deaths against PoC are already over two times more prevalent than restraint-related deaths against white people, but in six last year (out of a total 11), all of the victims were black or mixed heritage. INQUEST’s casework concludes starkly that disproportionate violence towards black people (and people with mental health issues) occurs in relation to officers’ misperceptions that they are more dangerous or impervious to harm/pain, leaving them “effectively dehumanised”. Devastatingly, Rashan’s treatment, and graphic reports of Edson Da Costa’s and Darren Cumberbatch’s arrests suggest as much. The racism that meant averagely-built Shiji Lapite, who also died in Stoke Newington Police Station in 1994, was described in court as “the biggest, strongest most violent black man” an officer had seen, seems still fully operational.

Like Rashan, Shiji was posthumously smeared, and this officer likely also exaggerated before a likewise prejudiced jury. This plays into another concern of interviewees: the apparent impossibility of legal redress for police violence. Aamna Mohdin writes that “every prosecution over a death in custody in the past 15 years has ended in acquittal”, leaving still no convictions made since 1969. Long legal machinations, which often seem purposeful, and an unwillingness to see law enforcement punished (although officers can be convicted for other crimes) help to normalise police inviolability. In often racialised cases, the disparity may also link to the aforementioned prejudice of invulnerability (as Stafford Scott argues, “[black people] get no empathy”) as well as more general institutional racism, as when lawyers prevented racist texts sent by Jimmy Mubenga’s killers being heard in court.

“the cheaper cost of intelligence-led operations like gang lists and the need to spin an amped-up risk for funding means austerity expedites increasingly militarised policing”

Policing tactics themselves also serve to reproduce racism. PoC are systemically, premeditatively criminalised, from “Stop and Search”, which still is 8 times more likely to target black people, to Joint Enterprise, which disproportionately punishes black people by 11:1. Guilty-by-association logic also informs suspected gang members lists, which, critics argue, mean “racial bias in the databases becomes institutionalised in police practice.” The vicious cycle of profiling, of course, doesn’t reflect reality: despite black youth being responsible for only 6% of serious violence by young people, “81% of the individuals on Greater Manchester police’s” gang list were black. Nonetheless, the Met’s Gangs Matrix has apparently influenced “education, employment and housing opportunities”, and Operation Shield, scrapped after LCAPSV and others objected, proposed punitive measures including eviction. Things could worsen, hitting working-class/communities of colour, as ever, hardest. Alongside aggressive lethal force policies and paramilitary gear (only a few days after Rashan was killed, Hackney police were filmed pointing guns), the cheaper cost of intelligence-led operations like gang lists and the need to spin an amped-up risk for funding means austerity expedites increasingly militarised policing.

The human cost of this institutional prejudice is violent and wrenching. Two weeks after the death of Rashan, Manuela Araujo, the mother of Edson Da Costa, another young black father killed by police last summer, and whose family have acted in mutual solidarity with Rashan’s, suddenly passed away, “consumed with grief”. However, where there is police violence, people continue to fight back. There are justice campaigns for victims, many of which are affiliated with the United Families and Friends Campaign, and groups like JENGbA, Y-Stop, StopWatch, Newham Monitoring Project, the Northern Police Monitoring Project, BLM UK and others resist or have resisted on multiple fronts. LCAPSV, for example, provide “know your rights” training, organise police monitoring, fight racist laws, mobilise court support for those murdered (as Black Lives Matter UK did for Mark Duggan’s family last year) or for those wrongly accused of assaulting police when resisting police wrongdoing, help press complaints, organise demonstrations, lobby, host community education and social events, work with other groups campaigning against state violence and more.

Film by Sapphire McIntosh @sapphire_mcintosh and Jennifer Edmunds