Cuts to maintenance grants reinforce that university isn’t made for poor PoC

Melissa Gitari

12 Aug 2016

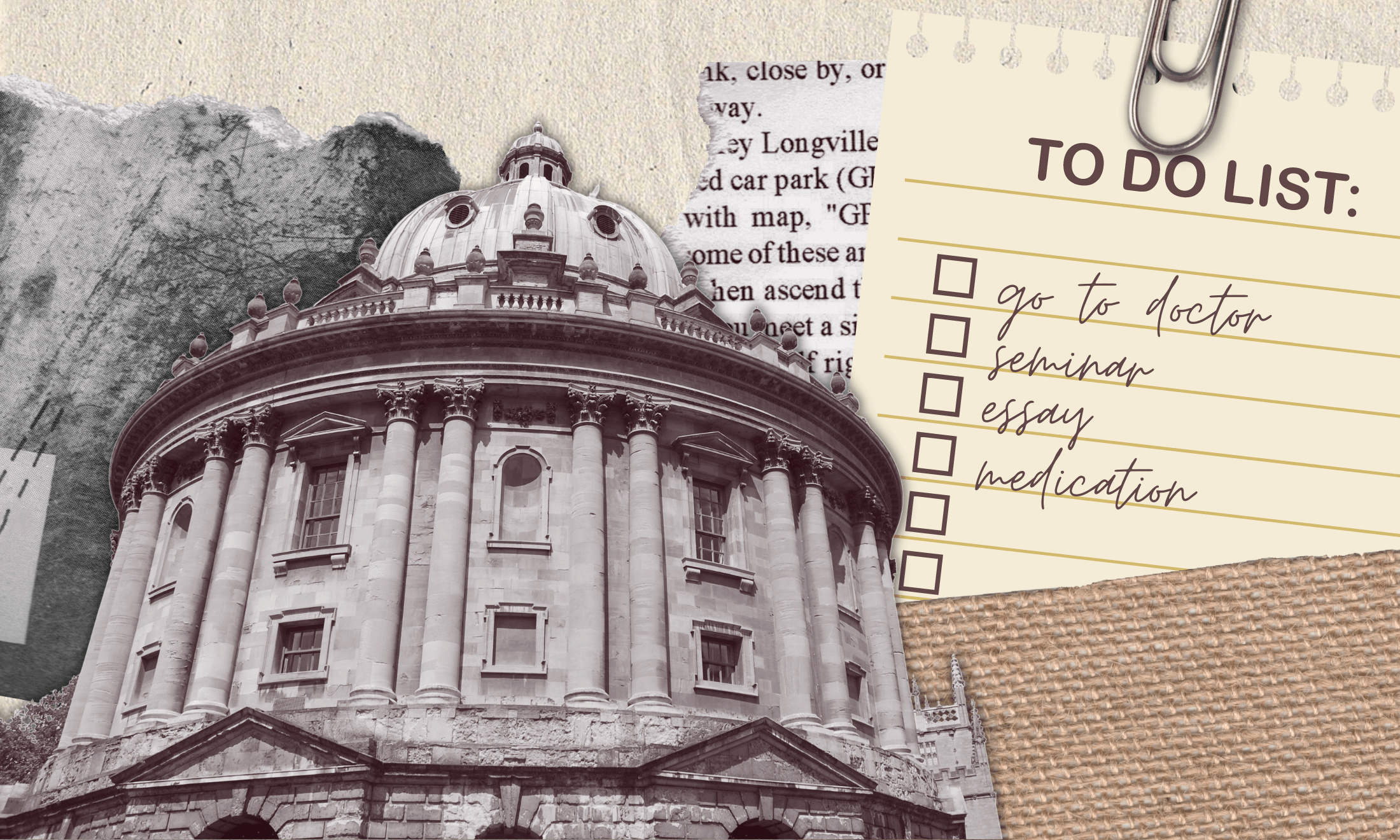

Just when you thought things couldn’t get any worse in Tory Hell, last week the government abolished maintenance grants for those entering university this September. For students like myself, whose debt would have been even larger without these grants, the news fills me with bitter disappointment. This comes a few months after the Tories issued a statement that they were planning to remove the cap on tuition fees in late 2017, allowing universities to charge even more than the already ludicrous £9000 a year. These policies, as well as destroying what little trust existed between young people and the government, disadvantage those at the intersection of race and low socio-economic income. Given the already Eurocentric and elitist nature of higher education, these cuts reinforce the idea that universities are not designed for poor people of colour to thrive.

The government’s main justification for these policies is that they are intended to bolster the quality of higher education, which will encourage all students, regardless of their socio-economic background, to apply to the best universities. More competition means better teaching and therefore a higher calibre of graduates. However, this pseudo-meritocratic reasoning is inherently flawed: how is a guaranteed lifetime of debt supposed to encourage working class and BME youths to apply to university? Describing these cuts as an effort to motivate disadvantaged students is misleading and irresponsible, as it distracts from the fact that such students stand to lose the most in the process.

‘The news that grants have been abolished fills me with bitter disappointment’

Moreover, the extent to which BME students even need an extra push towards university is questionable. The Telegraph published the results of a five-year study which found that all ethnic groups, including the ones that tend to perform poorly in school like black Caribbeans for example, are now more likely to attend university than their white British counterparts. Despite this, in my first year of university, I had to sit through an appalling sociology lecture during which the professor declared that black, Pakistani and Bangladeshi young people are less likely to apply to prestigious universities than their white counterparts, as their parents lack the cultural capital to encourage them to do so. I looked around the lecture theatre, which had a decent smattering of non-white people in it. How on earth did we get here then?, I thought. The lecturer seemed to be implying that people of colour are too ignorant to apply to the best universities, but this is obviously untrue. People of colour do make up a significant quota in academic spaces, despite the government’s best efforts to minimise this. The problem isn’t that poor, non-white students aren’t applying to university, it’s that universities refuse to acknowledge that they are there.

This idea of improving the “quality” of education is interesting, and I’m curious to see what specific measure universities will be taking to bring this into effect. I’m about to start my fourth and final year of uni, and so far the teaching I’ve received has simply upheld narrow, imperialist values. When I studied Oliver Twist in university last year, one of my lecturers compared the fictional character’s plight to that of actual enslaved Africans; this comment probably wasn’t made in malice, but it typifies the indifference towards the lived experiences of people of colour, not just in academia but in wider society too. Will increased tuition fees seek to rectify this, then? Will the money siphoned off the poorest students actually go towards developing a more well-rounded curriculum?

‘Texts that I deem important are viewed as an afterthought’

More importantly, will the funding go towards hiring BME lecturers? According to research by the University and College Union, in 2013 only one in fourteen professors (7.3 percent) in the UK were from BME backgrounds. As an arts student I find it particularly disheartening, only seeing white people teaching white stories, and even today I find myself questioning my degree choice. I’d had this idea of university as a cornucopia of knowledge, a place that would expand my mind and introduce me to a wholesome range of books and ideas. My excitement was promptly extinguished by bland and unimaginative reading lists.

Don’t get me wrong, I understand that Shakespeare played a crucial role in shaping the English language as we know it today, but why is his oeuvre part of a core module at my university while individual texts by Toni Morrison and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie only feature on optional units, units available exclusively in final year? The texts that I deemed important, that shaped my writing and self-perception, are viewed as merely an afterthought, something thrown in under the pale guise of “diversity”. Universities are fostering a hostile and isolating environment for people of colour, one in which whiteness is the main meal and everything else is just a garnish. If the government is serious about elevating the teaching standard, they can start by making sure that arts degrees reflect the full spectrum of human experience rather than a single shade.

While these cuts are an unwelcome change, we can only hope that from them comes a reformed higher education system, one in which middle class whiteness isn’t the yardstick we are forced to measure up to. The Conservative government may want us to think that poor and BME students don’t go to university but this is not true. We are here and we want better.