This morning (5th April 2017), healthcare workers, patients and activists from a number of groups came together in front of the Department of Health to erect a border checkpoint. The action involved activists dressed as doctors stood at a checkpoint, asking other activists dressed as patients, doctors and nurses, as well as anyone attempting to enter the Department of Health, to show their passports.

The action was coordinated by Docs Not Cops, a UK-based group that campaigns against the alarming policy shift towards charging migrants to access the National Health Service (NHS). The checkpoint sought to shed light on further barriers that will be introduced this month to prevent migrants accessing free healthcare in the UK.

As of April 2017, NHS Trusts will be legally required to check patients’ eligibility upfront and demand payment before providing care. These changes will see all healthcare workers, from GPs to receptionists, nurses to administrative staff, and doctors to midwives, performing duties more befitting of immigration enforcement. Even before attempting to diagnose a patient’s ailment and best course of treatment, doctors and nurses will be legally obliged to first racially profile patients to estimate the likelihood of them possessing British citizenship. Beyond that: whether they deem the patient to fit into a category of “migrant” that is ineligible for free healthcare on the NHS.

This shouldn’t come as a shock to us. In 2014, the Immigration Act introduced a healthcare surcharge on short-term visas, as well as a 150% charge on “non-urgent” treatment for certain “overseas visitors”. The threat of deportation hangs over those who are unable to pay, resulting in people being torn away from their families and communities simply for visiting a doctor or presenting at A&E. All of this is set against a backdrop of the NHS being pressured into sharing patients’ data with the Home Office.

This new obligation contributes to an environment where patients are already being racially profiled by healthcare workers trying to ascertain their eligibility for free treatment. One patient, Dena Bryant, was told by a nurse that she “did not look English, and [is] not white”. While there is no question that Dena, a British citizen with Native American heritage, is eligible for free healthcare on the NHS, the impact of this racial profiling was that the experience had “frightened” her, and she felt like “running away”.

One key consequence of immigration enforcement interests infiltrating healthcare provision is that those with precarious, complicated, or no immigration status are too frightened and unable to afford treatment. This fear is not unfounded. In 2015, hospital staff at Newcastle’s Royal Victoria infirmary called the police on an Albanian national with a suspected brain tumour, who had been treated at the hospital the previous year for a brain aneurysm, for “immigration offences”. They later stated that a “medical decision was made” that “the patient was fit for travel and discharge to seek treatment in his own country”.

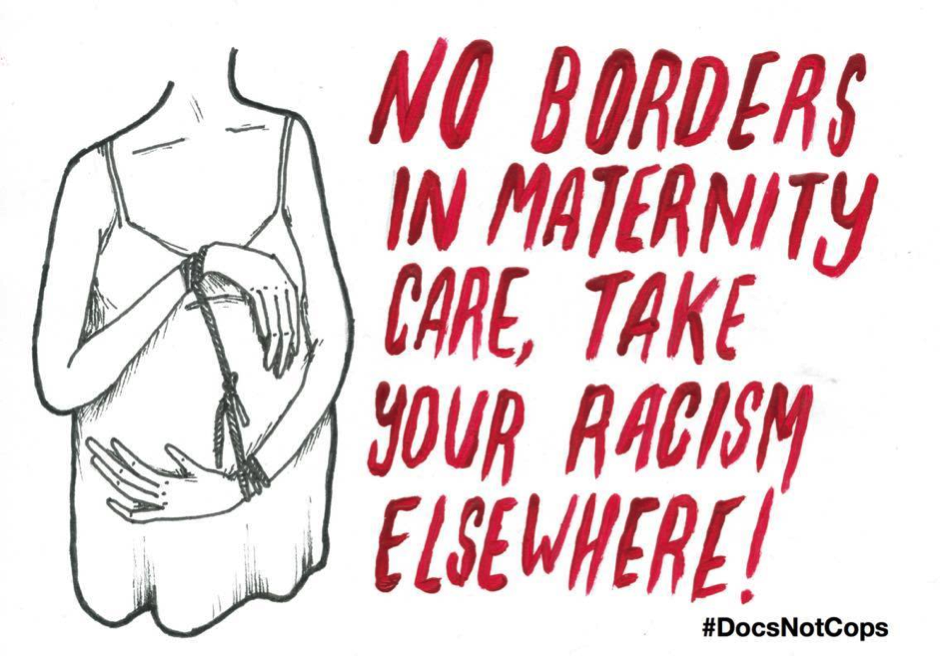

Racist and sexist stories in the right-wing media paved the way for these insurmountable charges for treatment on the NHS for all migrants, and in particular for pregnant women. There has always been a xenophobic interest and furore around the pregnancies of migrant women and specifically black women that is inextricable from both the historic racialised sexualisation of black women, as well as the protectionism of both whiteness and the British state.

The NHS, launched in July 1948 after World War Two by then health secretary Aneurin Bevan was created to provide “good healthcare free at the point of delivery to all UK residents regardless of wealth”. The NHS was, and in some regards continues to be, based on socialist principles, but as with most “national treasures”, almost immediately there were attempts to ‘protect’ it. In 1949, an amendment was made to the NHS Act introducing powers to charge those not ‘ordinarily resident’ in the UK, only one year since its inception. Subsequently, the NHS, itself heavily staffed primarily by nurses and doctors from ex-colonies and the British Commonwealth, was at the centre of a politically-motivated fiction depicting non-British “foreigners” as exploiting the NHS; a fiction which successfully trumped the realities of migration to the UK. The true exploitation of course lies in Britain expropriating wealth through hundreds of years of colonial endeavours in the Global South, allowing for the construction of institutions such as the NHS.

Far from Bevin’s socialist ideals, these new charges seek to make vital services inaccessible to those who need them the most, aided by right-wing and far-right political parties and press re-imagining people who are merely accessing basic healthcare provision as “scroungers” and “health tourists”. The right and centre right in the UK is notorious for drumming up divisive, racist anxieties about a demographic shift away from whiteness, which they claim will result in the white majority population becoming a minority. Nigel Farage’s anti-EU poster depicting thousands of asylum seekers walking along a path emblazoned with the words “BREAKING POINT”, reminiscent of Nazi propaganda, is only one example of many.

This bolstering of xenophobia by the press and politicians leads to the dehumanisation of migrants to the point at which they can be labelled “cockroaches” in popular newspapers. In turn, this paves the way for the political and popular justification of acts of ever more extreme cruelty towards those with complicated or no immigration status. One such act is the British government’s axing of support for search and rescue operations to prevent migrants from drowning in the Mediterranean Sea, claiming that this contributes to a ‘pull-factor’ by enticing people to turn up on Europe’s shores.

It should come as no surprise that the initial target of these healthcare charges are migrant women, whose experiences are already marginalised and silenced. This protectionist and nationalistic fixation with identifying and excluding those not deemed ‘deserving’ members of British society leads to instances such as that of a woman in 2014 whose visitor visa was due to expire. She miscarried at a late stage of her pregnancy, but was unable to afford the cost of being induced.

By this token, society views migrant women as having little or no value, and as such their suffering and struggles are viewed as insignificant. There is a particular cynical brutality in that these charges place nursing staff at the forefront of this oppression; a predominantly female workforce with a large proportion of women of colour and migrant women. These workers are forced to turn on those with whom they should be building networks of solidarity and resistance.

Thanks to Doctors of the World UK, a charity that holds clinics in London and Brighton for those with precarious immigration status too frightened to go to the hospital or to a GP surgery, many testimonies have been published which illustrate the shape and scope of the problem. These stories focus primarily on the impact that these charges are having on pregnant women seeking treatment on the NHS. One such story is that of Li*:

They asked me to pay £5,000 before I delivered the child. At one of my antenatal appointments, they brought me to a small room and explained I would have to pay more if I needed a caesarean. I felt very scared. There’s no way I can pay that much. I thought about not going to hospital, but I knew I couldn’t deliver a child by myself. I couldn’t cut the umbilical cord.

The introduction of borders within different facets of society, and specifically within the NHS, is not going unchallenged. Resistance to these charges are also taking place on an everyday basis. One volunteer from the group Birth Companions told Docs Not Cops that midwives at a conference she attended said that they would “overlook filling in papers, or tear them up, and made the point that they are not immigration officers and that is not the job they signed up to do”.

Docs Not Cops are working to empower healthcare workers to refuse to police their patients’ immigration status, and encouraging patients to lobby their local GPs, CCGs (Clinical Commissioning Groups), and NHS Trusts. Anyone can contact their local MP to express their concern about the impact of the charges. We are setting up a pledge for healthcare workers to express their refusal to police patients’ immigration status. We are also working with healthcare workers and patients across the country to create a national network of groups and individuals resisting the borders that have been created within healthcare.

Docs Not Cops’ particular focus is to overturn healthcare charges for migrants in the NHS, but we also support the work being done by other groups to dismantle borders in other aspects of everyday life, such as Homes Not Borders, Unis Resist Border Controls, and the Anti Raids Network. Our work to protect everyone’s right to the healthcare treatment they need is only one part of a broader struggle against Theresa May’s racist, sexist, and xenophobic “hostile environment”.

——-

* Li is a pseudonym used to protect the identity of the patient.