British artist Damien Hirst is no stranger to controversy, his works already receive critique of their value beyond shock factor, as well as questions of their originality. Faced with this latest scandal, we shouldn’t have expected anything less from Hirst’s ten-years in hiding.

Hirst’s returning exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale, Treasures From the Wreck of the Unbelievable has been on show for a month and has garnered four stars from the Guardian and five from the Independent, with Hirst even ironically heralded as “the ultimate appropriator.” In short, the exhibition is an extraordinarily extravagant comeback.

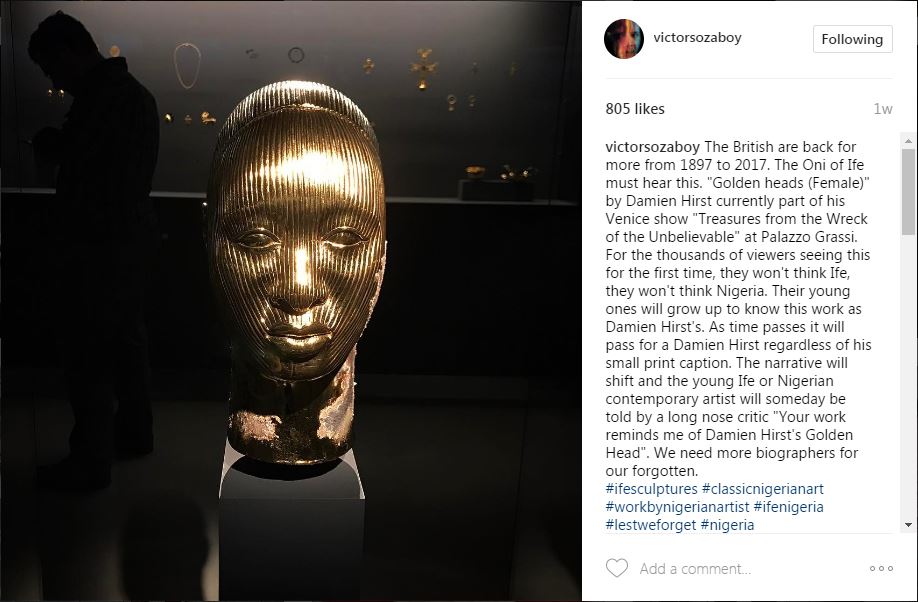

Yet it was only this week that accusations of Hirst’s Golden Heads (Female) copying a recognised 14th century Nigerian brass head, Head of Ife came to light when Nigerian artist Victor Ehikhamenor took to his Instagram account to “out” the Brit.

The artworks, or “Treasures” make up a mythological narrative of a shipwreck discovered in East Africa in 2008. The 189 grandiose objects spanning over two museums, are a kitsch attempt to stimulate the imagination. Statues at second glance resemble Hollywood celebrities and even Mickey Mouse.

But there’s nothing mythological about the very real Head of Ife, discovered in 1938 in Ife, Nigeria.

Speaking to Ehikhamonor he said, “As an artist I am not against influences and inspirations, but this is one step too far considering our history as a country colonised by the British and the events that happened in our cultural sector during their reign. That’s all.”

Ehikhamonor’s “that’s all” was poignant. It was not a statement of defeat, but rather a knowing statement of fact from one accustomed to the ruthless looting of African history and artifacts by colonial powers, like those in the Benin kingdom.

In an open letter to Hirst, Nigerian artist Laolu Senbanjo reiterated, “The original removal of this artifact was a crime to the Yoruba people and to re-create such a significant and important sculpture without truly understanding how sacred it is, its value and importance to its original owners, not sharing that information and just washing away its importance that it holds to the Yorubas, a group of over 40 million people within Nigeria (not counting those in the diaspora) is just horrendous.”

Hirst’s acknowledgement of the origins of the Golden Heads (Female) stated that it were “stylistically similar to the celebrated works from the Kingdom of Ife.” He went on to declare the exhibition a much needed escape from the dismality of current politics, “with all the liars running our governments, it’s far easier to believe in the past than it is in the future.” Yet, his emphasis on imagination, in having something to “believe in” in our post-truth world is merely a scapegoat for improper research.

There is a fine line between inspiration and appropriation, and Hirst seems to have no problem crossing it.

It is a privilege to ignore the history of others, a history that isn’t whitewashed, a history that isn’t Western. But how long can the commercialisation of colonised nations and their art be disregarded? Hirst can expect to sell each piece of the Wreck for $500,000 to $5 million, his arts exuberant cost scrutinised at the expense of uncovering careless referencing. Like colonialism, he is profiting from a narrative that is not his own.

Damien Hirst thrives off scandal – the shock factor, the “extravaganza” of his works (see the dead shark suspended in a tank, the maggot-ridden cow’s head, the Swarovski covered 18th century skull etc. etc.)

This time around his self-entitlement has come for him. You simply cannot feign ignorance when Nigeria finally have their first respective Pavillion at the 57th Venice Biennale, and when the exhibition of veteran artist, Ehikhamonor, A Biography of the Forgotten specifically uses hundreds of Benin bronze heads to highlight colonial theft and the primitivisation of Ancient African art.

Cultural appropriation has become a buzzword that leaves many now senseless to the long-term domino effect of Western artists, designers and celebrities alike “appreciating” the traditions and art of the colonised without proper referencing. They reduce rich narratives to “tribal chic”. They perpetuate a cycle that defends the colonial ethnographer and archaeologist; appropriation legitimises the entire colonial backbone as a “civilising mission” that justified human and cultural exploitation.

As Mems Ayinla, author of Diaries of the Afro-Saxon puts it, “under the guise of being liberal and progressive, these Western artists are making the same errors of their forefathers by failing to acknowledge black labour, black art.”

With so little media coverage in Britain, it begs to question why Hirst’s scandal hasn’t made the headlines.

Maybe we’re all tied up with May and Corbyn? Or maybe it’s yet again a very British way of disregarding our nation’s involvement in a colonial cultural massacre.

There’s nothing kitsch about appropriation. Hirst – when you can’t claim originality, claim at least sincere acknowledgement of your sources.