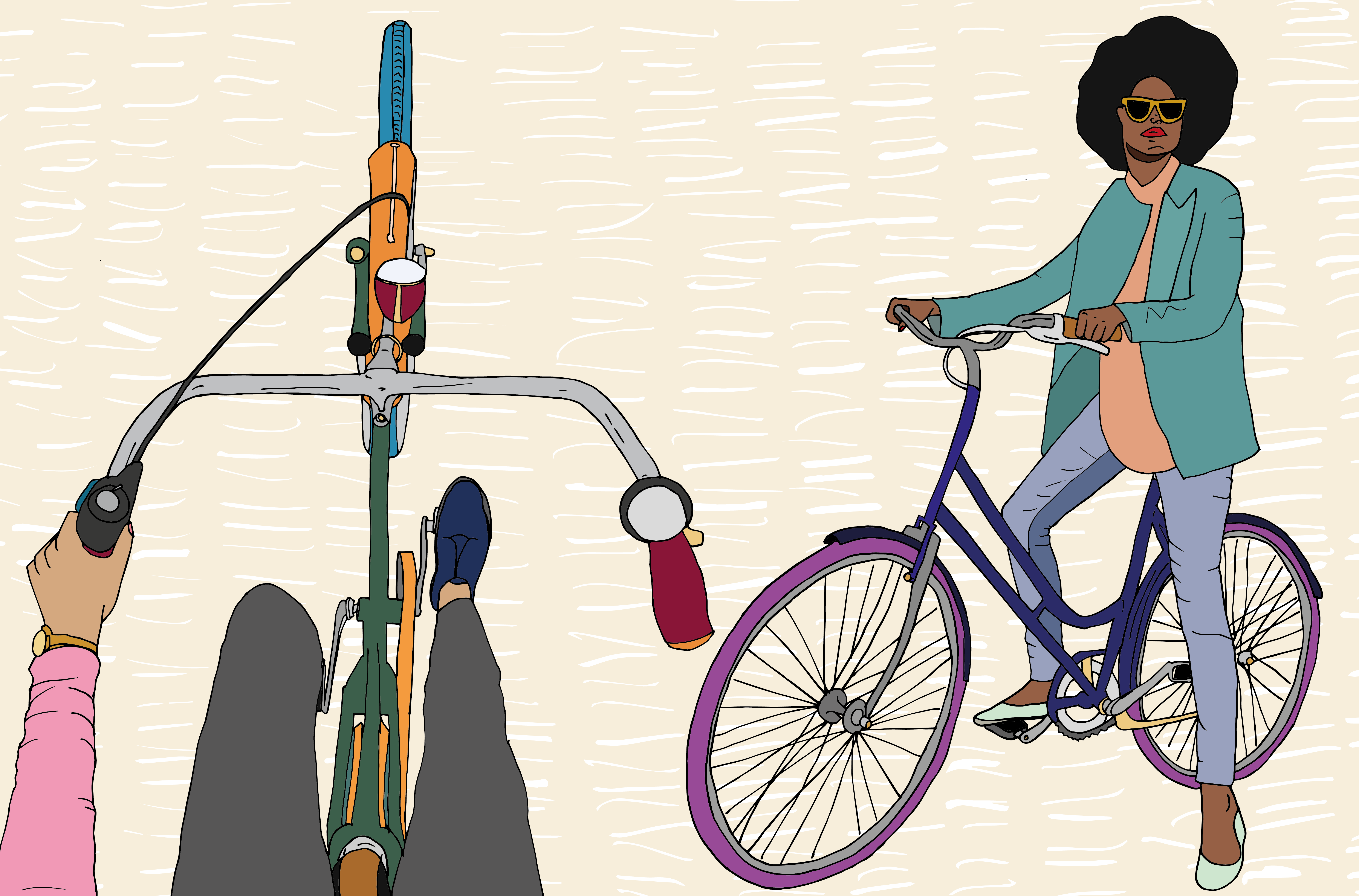

I learnt to ride a bike aged 28. A combination of factors stopped me from learning in childhood. I had multiple surgeries on my legs, I had no family members who cycled and I lived in a deprived and industrialised town with poor infrastructure and no cycling initiatives that I knew of.

My first year of “cycling” was limited to a rickety and repetitive jaunt on a path in my local park in Bristol, furnished with panic and expletives whenever a person or dog approached. It was only in Summer 2017, aged almost 30, that I finally ventured around Bristol’s harbour. It was beautiful and exhilarating. Unlike walking, cycling is free of pain and makes journeys like going from Bristol to Bath on the old railway path possible—journeys that I’d struggle to do on foot.

Speaking to friends, all those who hadn’t learnt to ride in childhood were raised by (mainly BAME) working-class immigrants. I decided to dig deeper and found that wider research backs up this discrepancy: BAME people are a disproportionately small percentage of those who cycle. We don’t learn as children because cycling gear is expensive; cycling initiatives are written about in English; and, in places like the Caribbean and the Indian subcontinent, it’s not the norm for girls to use a bike.

But what happens when we do venture into the cycling world? From my own (albeit novice and still wobbly) experience, I worry that as well as the ubiquitous hazards of careless drivers and meagre cycle lanes, women of colour are vulnerable to verbal abuse, beyond levels that white people, men, and of course, white men, are likely to experience. A caveat: as I’ve said, this hypothesis is based mostly on my own experience. There’s no research about this, but perhaps there needs to be.

So, to illustrate with my own experiences, here is a summary of just some of the things that have happened to me. One hot day, I was cycling on a path in my local park, when a woman on a bench said she hated cyclists and that she hoped I’d get knocked down by a car. When I stopped to ask why she’d say such a thing, she continued on a tirade until I cycled off. Another day, near Bristol’s harbour, I was cycling on a cycle path, when a woman shouted at me, “bikes should be on the road, get off!”, apparently oblivious to the several white guys on bikes around her.

And the one that sticks out most: I was on a pavement (wrong of me, I know, but I was going extremely slowly and had just started out, and my only other option was a busy A-road), when a man, whom I was nowhere near, came close to my face and told me I should be on the road. When I explained that I was learning, he said, “I don’t care. In this country, we cycle on the road, and if you don’t like it, you can go back to your own country.”

Through Twitter, I connected with other women of colour who cycle, including Zoe Banks Gross, who is doing an array of amazing things to make Bristol a more sustainable and healthy city. One of her many roles is teaching basic cycling skills to groups of BAME women who can’t ride. She explained, “[The groups provide] a positive space where women feel like they can do something without being ridiculed or singled out. It’s hard to find those spaces. When women get confident on a bike, they feel empowered and more entitled to use that space”.

Some women who finish her course will then join Zoe’s Kidical Mass bike rides with their children: “it’s so inspiring. It’s just amazing to see them get that confidence.” But for other women, cycling is difficult to keep up. A course member was racially abused on a cycle path just after finishing a lesson, and although she was walking, the experience has deterred her from getting on a bike again. “If you’re on a bike, you’re putting yourself more out there to be abused,” said Zoe, neatly summing up my own thoughts.

Twitter also led me to Rose from Bristol, a confident cyclist, who shared an experience of sexism: “While trying to avoid some kids running about the cycle path, whose parents/carers walked on the path, I politely said, ‘the other side is the pedestrian path’. Some builders sitting on a wall told me to ‘shut up, woman’. I refuse not to use my bike though; it makes me happy.” Like Rose, abusive experiences won’t stop me from cycling, but they do add an extra layer of anxiety whenever I mount the saddle.

It goes without saying that changing prejudiced attitudes to women of colour and cyclists, never mind women of colour who cycle, is a difficult feat. So what can we do?

For one, we can put pressure on authority figures to improve infrastructure. About women of colour, Zoe says, “if you build it, they will come”. But in his State of the City address this month, Bristol mayor Marvin Rees made no mention of cycling infrastructure, instead talking about his controversial £2.5 billion mass-transit system project. I hope that he pays attention to voices like Zoe’s, who argues that “giving space back to people would help make getting around the city easier and friendlier.” She continued, “if we’re walking or cycling, it’s so much easier to engage and interact with people. That’s what we need more of right now in these difficult times we’re living in.” I wholeheartedly agree.

Another thing we can do is normalise the sight of women of colour on bikes. Let’s have more role models like Jools Walker. And let’s create more spaces, like the USA’s Black Girls Do Bike movement, for women of colour to ride together. There might be barriers: communities from which such a group might have flourished, like Roll for the Soul and Hamilton House’s Bristol Bike Project, are closing or under threat. But it’s a worthy aim, if it means improving our rightful claim to the streets.