With the new season approaching, new film releases are imminent and the end of 2018 brings yet another batch laden with outdated colonialist ideas. Jungle is a film that stars British actor Daniel Radcliffe and is directed by Greg McLean. The biopic feels like a rehashing of old empire tactics. Shaped as an adventure story, Jungle is set in the heart of South America in the Bolivian Amazon rainforest. The narrative follows one man’s journey against all odds but, curiously, omits any Latin Americans. It’s a modern feature with an obvious white gaze, which doesn’t include any acknowledgment of the people originally from the region.

There is a total lack of indigenous identity, showing one white European man’s (Radcliffe) journey through the Amazon, obsessed with the notion of discovery and a “new world” fantasy. There is no perspective of the Amazonian people here. The idea that they might not want to be discovered or observed by the foreign European travellers is clearly overlooked. This disregard exemplifies an industry that still, even in 2017, produces through a traditional imperialist lens.

It is a narcissistic journey, one that centers on proving “one’s self” or capturing the essence of “one’s self” by adopting the footprints of another person’s habitat. It is always seen as something temporary. The “travellers” are in the Amazon for a short while and the safety net of a meeting point and being rescued on a boat falls short of the true experience that native people live through every day. In the film, the intentions are transparent from the beginning; the eagerness of the travellers to explore these foreign lands is seen as entertainment and a chance to help themselves better their own careers. At one point, Radcliffe states that he promises to capture photographs of indigenous tribes so that they can be published “in the National Geographic.” It feels like a kind of trophy hunt.

“This disregard exemplifies an industry that still, even in 2017, produces through a traditional imperialist lens.”

It is not hard to see why historic representations get repeated like this, the idea of the “seduction with the primitive” has been deeply embedded in western culture for hundreds of years. In the west, nature has often been depicted as an obstacle that should be challenged and overcome. This also included any inhabitants as savages, inherently opposed to what is deemed as “civilization”. Nature, and life in “natural” habitats goes against the ideals of western culture, and thus those residing outside of western culture and civilisation are seen as “primitive” and completely undermined by this discourse. The protagonist, in Radcliffe, performs the activity of dominating the land in order to prove his superiority over others. It is the reason for him entering the Amazon – and the battles against nature are the actions of overpowering and self-appointing his authority in a new world.

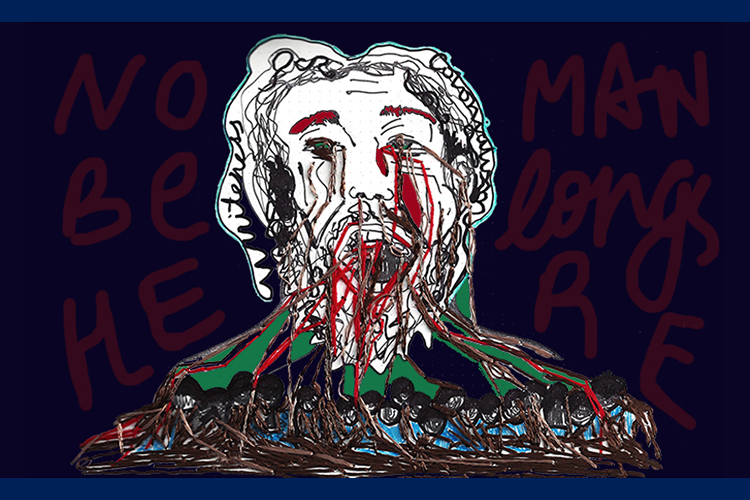

The films centers on the jungle-roughed Radcliffe struggling to survive the unforgiving conditions whilst the drum-beating catch line, ”No Man Belongs Here” echoes in the background of the trailer. This is a line which in itself re-affirms colonial ideals of new people entering new worlds, completely erasing the footprints of the indigenous population and people who have lived and survived in the same place before western intervention. Clearly these communities are not considered human, worthy of recognition. It suggests that land such as this, too foreign for the white man, should not be inhabited by any people, ever. It serves to dehumanize the “other” expressed as the natives of the jungle, by misrepresenting the way the “other” has chosen to live; insinuating that land exhibited in the film should be inhabitable rather than represent the people who live there as intelligent and the land as fruitful.

“Land such as this, too foreign for the white man, should not be inhabited by any people, ever”

Despite the shocking deception of the film, many thousands of Amazonian tribes do exist and have done for many thousands of years. It may come in the way of a “good story,” but the reality is that for many thousands of years indigenous tribes have built communities and lived abundantly in this part of the world. A production like this ignores the fact that historically Europeans have been intruders, often with the most extreme consequences. This began with Spanish colonisation in the 16th century, and continued more recently with American big business bulldozing land for global fast food farming. The real “against the odds” story lies with the citizens of the Amazonian countries fighting to keep their own heritage alive. Surely this a more valuable storyline?

These types of representation or non-representation are what inform people’s views, lead to prejudices and fuel discrimination. Little is understood of the rich culture and daily lives of people on this continent and so these representations perpetuate “othering”.

“The real “against the odds” story lies with the citizens of the Amazonian countries fighting to keep their own heritage alive. Surely this a more valuable storyline?”

When Christopher Columbus made his voyage through to the Caribbean islands and parts of South America, he encountered the indigenous tribes of the Amazon called the Arawak. In his diaries he noted them as an inferior population, one that can be moulded and taught the “right” way to live. In his words: “they ought to make good and skilled servants, for they repeat very quickly whatever we say to them. I think they can very easily be made Christians, for they seem to have no religion”. Columbus assumes a lack of knowledge and heritage and makes them appear worthless, holding no value. This dehumanisation legitimised the slaughter and enslavement of these populations, leading to a 90 per cent reduction in the population of indigenous tribes living in the Amazon after the invasion of Columbus and European settlers. During the initial periods of European invasion, one of the most forefront endeavours of colonization was the eradication of the population of such tribes.

Historically, these people were even stripped of their own tribe names and branded instead, “Indians”, a title of “foreignism” given to them by the western European colonials. It is the word “Indians” which is continuously given to the Amazonian tribes by Radcliffe and his traveller friends, despite knowing their tribe names and heritage. The division of Europeans as human versus tribes as non-human is the main reason why indigenous groups in South America had been so preoccupied with achieving recognition on the world stage. It is only in the last decade that progress has accelerated and indigenous people have gained entitlement and acknowledgment from the new Evo Morales government in Bolivia, which has fought for the preservation of land, indigenous people and their practices.

“This film obviously has a substantial budget. It has Daniel Radcliffe in the lead role. Why couldn’t a Bolivian actress have been employed?”

The offensiveness continues in the film’s casting. A tall Australian model/actress Yasmin Kassim was chosen to evoke an Amazonian woman, fictionalized as a fragment of imagination by the ill nurtured Radcliffe. The clear disparities of her features despite the heavy makeover were apparent for me as soon as she enters the screen. Her height, long face and western features stood out despite the make-up designed to make her appear more indigenous. Beyond the make up, the figure of the Amazonian woman in the film is clichéd, with an angular haircut, dirtied face and beaded necklaces – so strikingly disingenuous. This film obviously has a substantial budget. It has Daniel Radcliffe in the lead role. Why a Bolivian actress could not have been employed to play the part of this Amazonian woman seems confusing. If money was not the obstacle, what was?

Ironically, the author whose story the film is based on, Yossi Ghinsberg, is an Israeli, a factor that was seemingly skated over casting of the film in favour of a less than impressive accent by Radcliffe’s performance. Moreover, it’s a real shame that Ghinsberg’s effort in ecology work after his time in the Amazon has been, quite frankly, tainted. His work has been recognized for its connection to and respect of indigenous cultures so it is a shame the film does little for the representation of these indigenous groups despite Ghinsberg’s experience in this field.

Instead, the film reinforces the same Christopher Columbus-esque battles of winning over the land. The seizing is in fact metaphorical of the entire film; the endurance of trekking through muddy soils and beating jungle bushes through a white man’s journey is the ultimate colonial statement.

It is evident that colonial representations like Jungle have been outworn in the world today. Tales such as these have become repetitive and it is important to see history from different angles if we are to truly progress. There has to be more investment in diversifying film-making too. This can provide more dimensions to storytelling and will be the intrinsic tool in breaking down these colonial ideals in films. We already have history books telling us about Columbus, we need films to represent a pioneering step forward and a new narrative.