Facebook has given me some of my first introductions to how people see British Pakistani’s like me. Scrolling through the news-heavy feed, I see on a daily basis stories on immigration, the lack of integration in the UK and poverty and rape on the sub-continent. Yet despite this heavily negative focus on stories about people like me, Facebook was also the first place I was educated about British colonial rule. It was an interview with Indian MP Shashi Tharoor, and he spoke about how Britain’s “historical amnesia” towards the realities of colonial rule needs to end. But why was I learning about this through social media, and not through school?

I went to a majority white suburban middle-class school and, for me, feelings of exclusion and alienation manifested themselves inside the classroom in the form of history lessons, as opposed to outside in the playground.

As a child in primary school, I always found history lessons to be an uncomfortable time. I can distinctly remember feeling like an outsider as I failed to see brown people like myself represented in any of the topics we covered. “Who am I kidding?” 10-year-old me would think to herself. “I’m brown and Asian; there were no brown people in England during the Victorian times.”

“The irony is that while there may not have been brown people living in England at the time, Britain’s colonial presence in India was at its peak”

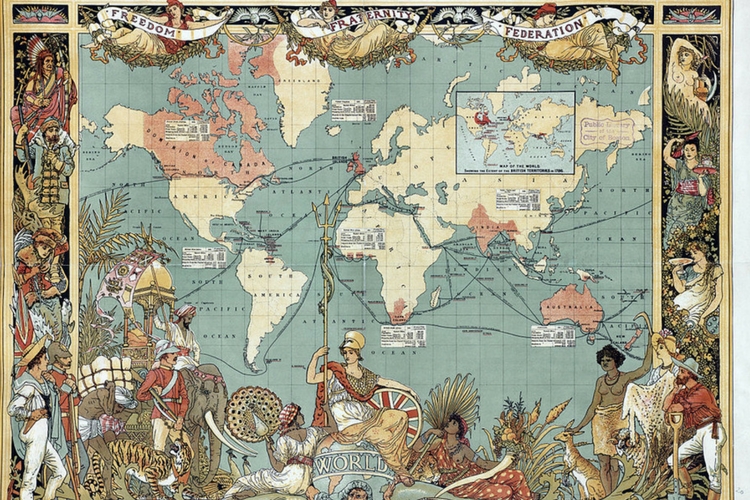

The irony is that while there may not have been brown people living in England at that time, Britain’s colonial presence in India was at its peak – a reality that the education system fails to highlight much at all. At a recent talk I attended entitled Decolonising Partition, a member of the audience joked that all the British education system had taught him about the imperial rule was that some English Lords went over to India to play cricket. Though this was met with laughter from the crowd, this kind of ignorance towards the impact of the British Empire and the subsequent Partition of India is all too real for many young British Asians.

While we sat in school learning about Oliver Twist, Fagin and the chimney-sweeping children of Victorian Britain, what was ignored was the fact that at the same time, the material resources for these austere industrial factories had been plundered from India, which was then under British colonial rule.

When the topic of WWII was covered, every child in my class’ hand shot up when our teacher asked whose grandparents had fought in the war. This was followed by the feeling of pride and admiration at the elderly English grandparents who had helped defeat Hitler and his Nazi regime. What is often rarely mentioned, however, is the contribution and effort of nearly 2.5 million Indian soldiers that fought and died in the same war. Including this fact would help countless British Asian children see people like them involved in the greatest narrative this country likes to project (Britain defeating Germany).

“Talking about the struggle leading up to and after Partition can be a taboo subject”

My knowledge and understanding of British colonial rule was mostly autodidactic. Of course, the celebrations of August 14th (Pakistan’s Independence Day) are always given importance in my family and the wider Asian community. But while our family like to celebrate our respective independence days, talking about the struggle leading up to and after the Partition can be a taboo subject. Often, families who have witnessed the trauma of partition struggle to talk about it, and when they do, they risk falling into demonising the “other”. Whether that be the Hindus, Muslims or Sikhs, this demonisation is in compliance with the “divide and rule” mentality implemented by the very imperialists that caused the problem in the first place.

We are the last generation whose grandparents lived through the horror and reality of the Partition, but future generations won’t get the privilege of witnessing their narration first hand, if they narrate it at all. It shouldn’t rest on the shoulders of our grandparents to relive their trauma in order to teach us what should be taught in schools.

While some may argue that there are opportunities to learn about colonial rule and Partition in higher and further education, this isn’t good enough. British colonial history needs to be taught to a collective majority rather than a select minority of students who wish to pursue it out of personal interest. By teaching it in schools at a young age, brown faces in history will be normalised and become synonymous with being British – something which will reduce racism, xenophobia and fear of “the other”.

“We are the last generation whose grandparents lived through the horror and reality of the Partition”

In today’s times, where the rise of right wing parties such as UKIP and EDL have entered the dominant discourse of politics, the anti-immigration sentiment is high. Prejudice starts at a young age and children learning about the diverse history of the UK will grow into accepting and more open adults.

For those that argue that it is too gruesome a topic or too sensitive, I say that if we can learn about WWII and Nazism in Year 6, and chimney sweeping and child exploitation in Year 5, then the same applies to colonial rule and Partition. The Partition needs to enter into the main narrative of this country’s history, rather than being something which features in a video that pops into our newsfeeds on the rare occasion an outlet decides to cover it.