To be black, British, and female in the creative industries is a challenge. To have your work recognised and find longevity in a fleeting, and often times, superficial world dominated by men and white women is an even greater challenge.

Since the 80s, particularly in music, there have been artists who have had brief sparks of critical acclaim, from Soul II Soul to Gabrielle, Des’ree, and Eternal. There are acts, such as the inimitable Sade, who could be considered unusual in her incredible success. She is regarded as the most successful female solo artist in British history even to this day – but the visibility and longevity of black British female artists in general is an ongoing issue.

Talent shows such as the X Factor gave us the likes of Alexandra Burke, Leona Lewis, and Misha B, who have each experienced varying degrees of success. Lewis in particular found her feet in America, as is often the case with black British talent (musicians and actors alike). Even double Brit Award winner Ms Dynamite, who experienced huge success at her peak, spent time attempting to rebuild her career and gain a revived underground following after taking a break and disappearing into relative obscurity.

In 2011, Sabrina Washington, former lead singer of Mis-Teeq, told the Independent there was “a lot of black female talent in the UK”, but the lack of platforms on which they can be celebrated leaves them in the shadows, not for want of trying. Washington herself was part of one of the UK’s biggest female groups at their peak, drawing comparisons with Destiny’s Child and earning seven consecutive Top 10 singles and brief international acclaim. While former co-member Alesha Dixon went on to pursue a respectable solo career, Washington’s trajectory did not follow suit: “when I got back into the UK music scene and started to have meetings with A&Rs, I met a brick wall,” she said. “I think it’s because they didn’t know how to market me, I was quite astounded considering how many records I sold with Mis-Teeq. There was no one out there willing to invest in me, so I had to do it myself.”

As with Lewis and fellow black British female singer, Estelle, Washington conceded to pursue a career abroad, as it is widely believed other countries are more receptive to black female singers, particularly America. Beverley Knight, one of the most consistent black female artists in the UK since the 90’s, said: “I remember always hearing this statement in record label circles: ‘It’s so hard to market black artists’. There are two general assumptions: that most black female singers can seriously sing as a rule, and they generally sing R&B/soul. Therefore, a great voice does not make her exceptional. The other side of this situation is that a female of any other ethnicity who has a great soul/R&B voice stands out immediately. We have all heard the phrase, ‘she sings like a black girl’. That singer is already a marketing dream, and stands more of a chance of success.”

The ongoing and ever-present need for black women to invest in themselves is why many of us are taking our careers into our own hands and using our limited resources to make space for and give platforms to our sisters. In 2013, I founded Intersectional Black British Feminist platform, No Fly on the WALL. Starting online, we created space for marginalised voices, particularly the voices of black British women, who seemed to be invisible, swallowed by the mostly American definitions and narratives of what it means to be a black woman.

Fast forward to the present day, we have moved our work offline in the form of the No Fly on the WALL Academy and we organise monthly events, brunch time discussions, sista circles, workshops, and provide space for black women to network in and mingle. Too often the contributions of black women in the arts, music, academia, social justice movements and more are erased or downplayed. When you are given no space in which to use your voice, how do you begin to express yourself and voice your joy or your pain?

Throughout history, black women have used music and poetry in particular to find their voice and share it with those who would rather not listen. Black British women have contributed to the rich tapestry of music and the spoken word scene in the UK for decades, from the beautiful lovers rock of Jean Adebambo, the soul of Shola Ama and the smooth floaty jazz of Corinne Bailey Rae; to the booming vocals of Shirley Bassey, the indie-electro-dance-punk of VV Brown, the clever word play and swagger of Lady Leshurr’s grime; and the lyricism of Emeli Sande.

Poets like Dorothea Smartt, Patience Agbabi and Yrsa Daley-Ward have used their art to put a spotlight on what it means to be a Black British queer woman; and Warsan Shire’s writing has sent ripples across continents for its focus on migrants, refugees, and identity. The current Young Poet Laureate for London, Selina Nwulu (a position previously held by Shire), has received critical claim for her work. Although it is true that there are black women breaking the mould, with some even being bold enough to place their heads above the parapet, we are still in need of more opportunities in which to showcase all we have to offer.

When I asked black British-Nigerian poet, Dylema, what inspired her to become a poet and spoken word performer, she said: “I had a really eventful upbringing growing up in Nigeria and migrating to England. I went through several moments that required me as a ‘woman’ to be silent. Poetry became my voice at an early age it was a way of saying things I couldn’t really say outright. Words have been my oldest and closest friends and I turned to words when I needed to be heard.”

Turning to words and using creativity as a form of expression is a sentiment shared by many on the margins of society. When asked how black British women were contributing to the creative explosion in black Britain, particularly in the underground and alternative scenes, Dylema said:

“I find that black women are currently realising within themselves the power they are capable of. In the underground scenes I think there are a few black women who are pushing through to the forefront, although there are still not enough representations of us to portray a real change.”

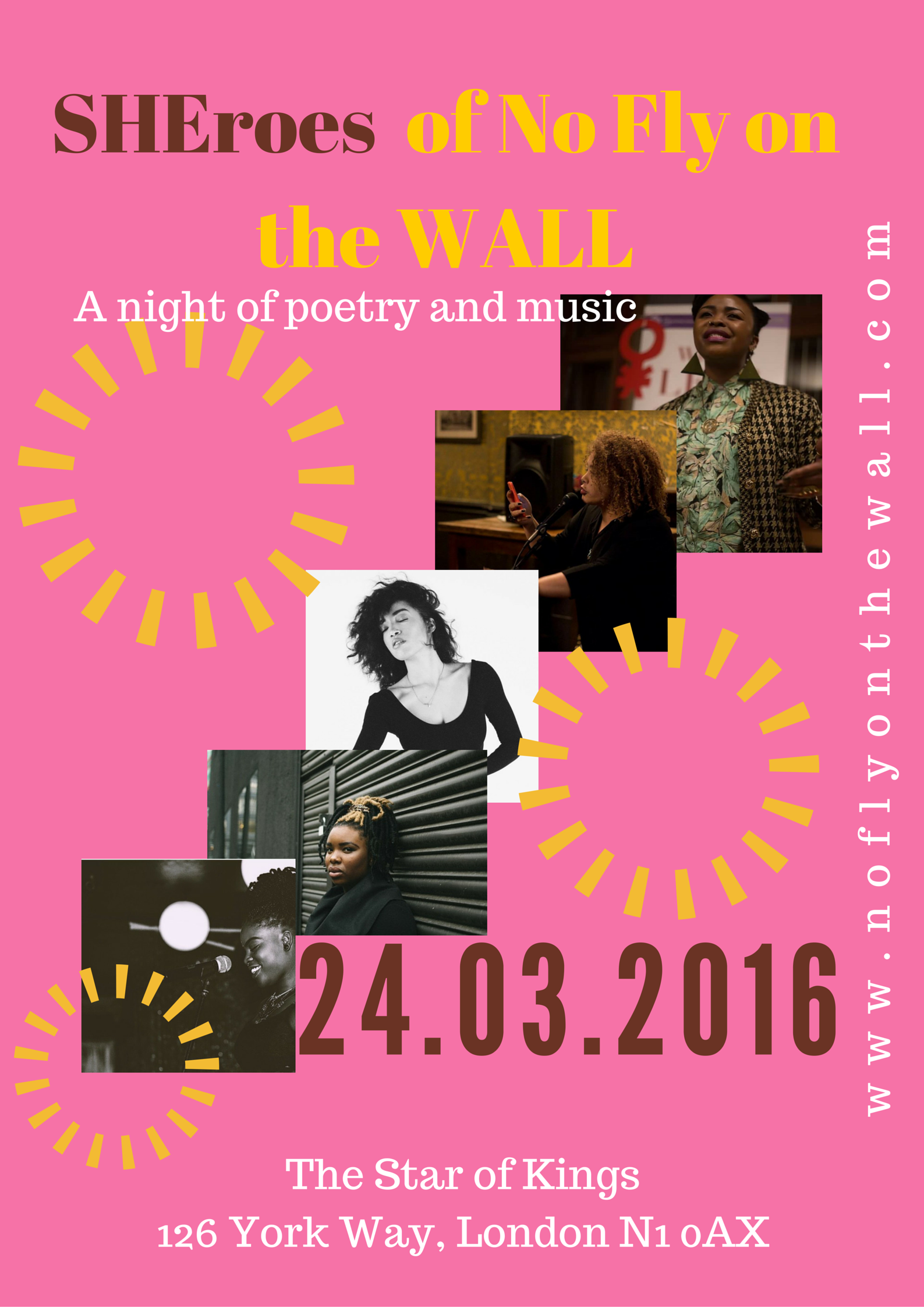

As in the 80s, 90s, 00s, and even now, black women have to push that bit harder to have their achievements met with the celebration they deserve. This is is why, as well as our regular monthly events, the No Fly on the WALL Academy has organised SHEroes – a night of celebrating the talents of black British female artists.

Last November we debuted the event at SOAS to a packed room of excited attendees who were there to see the likes of Tania Nwachukwu, Theresa Lola, and Vivienne Isebor perform.

Tomorrow night we’re opening our stage to more bright and beautiful voices: 19-year-old London singer-songwriter Savannah Dumetz will be serenading us with her soulful, sweet vocals; 21-year-old Janel Antoneisha will enrapture us with her haunting rhythm and blues; and poets Antonia Jade King and Dylema will, through their candid outpour of emotion, remind us that the pool of Black Britsh female talent is truly bottomless. I myself will be taking to the stage once again and sharing poetry from my upcoming debut collection of poetry, Elephant.

SHEroes of No Fly on the WALL takes place tonight at The Star of Kings in London. Tickets can be purchased here.