Brown women have sex. We like to have sex. In relationships, out of relationships. Sex is for pleasure, and who doesn’t like pleasure?

As we know, aside from pleasure, another outcome of sex is pregnancy. I found out I was pregnant at the end of last summer. I was enjoying summer in London, making plans for carnival and catching the last of the city sun. I had been feeling nauseous and hungry all weekend – I knew something was off. My IUD had failed me. After telling my partner, I made an appointment with my GP, and had a referral to the local BPAS (The British Pregnancy Advisory Service) clinic by the afternoon. I was so focused on ending this pregnancy as soon as possible – it consumed all of my energy. After what felt like an age; a few days later, I was having a consultation. As I sat making awkward self-deprecating jokes to cope with my discomfort and stress, the nurse was excellent – she was familiar with this behaviour, and gave me all the information I needed. I just wanted this to be over, to be back at work and back to normal; and the key to that was to have this thing removed as soon as possible.

The pregnancy made me violently sick – I was barely able to eat a rice cracker a day. The morning sickness wasn’t just stressful because of how it completely floored me physically, but it also made hiding the root cause so difficult. My family home has almost always been a sanctuary for me, providing a physical and emotional base for everything. Living in an extended family is a magical part of being brown, but it means that keeping things private can be challenging to say the least. Telling my family was never going to be an option – and so I knew my home would be far from my sanctuary until this was over.

“Living in an extended family is a magical part of being brown, but it means that keeping things private can be challenging to say the least. Telling my family was never going to be an option – and so I knew my home would be far from my sanctuary until this was over.”

I’m a third generation South Asian woman, and I grew up in a relatively liberal family. When I say liberal, I wasn’t allowed to have a mobile until after I had finished my GCSE’s, but I was allowed to study abroad while at uni. I was encouraged to think critically about the world, question everything, and never take anything just at face value. As an adult, I’ve eaten space cakes with my Mum, and she’s aware I smoke weed. Overall, a supportive, rounded and chill environment, for the most part. Sadly, this liberal attitude NEVER extended to romantic relationships, and certainly never to sex. Growing up, the only thing I heard about sex from my family, was that I wasn’t supposed to have it. Ever. Until marriage, where the subtext indicated it was my duty to pop out beautiful baby boys that would belong to my husband’s family. As I got to my later teens, my mum and grandmother would tell me: “Never do anything that would make us walk with our head down”. I knew what they meant – don’t have sex until you’re married, or you’re a disgrace to us.

This message never felt like it was shared to protect me or my emotional well-being, but rather as a reminder that my vagina was a vessel for family honour- that would be broken should I choose to exercise sexual agency. I became sexually active in my late teens, and while I knew it was the right choice for me I always felt suffocated by the underlying shame and guilt; petrified that despite my silence, I would be discovered. It wasn’t until I was in my mid-20s that I was able to share this information openly with other women from brown communities – mainly for fear of being judged and shamed by those who should be allies and sisters. But I always knew the misogyny ran deep, and the indoctrination kept us silently separate. Over the years, I have been able to unlearn – but it has not been simple or quick, and I’m sad to say that having to hide this abortion threw up all of those feelings of shame, isolation, and guilt again.

A week after my initial consultation, I trotted off to BPAS to take the abortion pill; nervous but happy this was drawing to an end. I went home, had a period, and felt relieved. I wanted to eat and live without something growing inside me that I didn’t want. I took the routine pregnancy test afterwards (and another one to be sure), and they confirmed I was no longer pregnant. As the weeks passed though, I was still struggling to eat, and experiencing some nausea. It wasn’t until I went to the GP six weeks later that I did discover that I was, in fact, still pregnant. Stunned, I got an appointment immediately at BPAS. The nurses were as shocked as I was. I couldn’t react. I was just silent. The transvaginal ultrasound had me at 18 weeks pregnant to be exact. In my shocked state, I recall asking if the pregnancy was still viable; the nurse told me that it was. Under no circumstances was remaining pregnant an option for me, but knowing the pregnancy was viable added to how trapped and suffocated I felt in my own body. I had been feeling twinges that I had assumed were period related as my body was adjusting to having had the abortion pill. It dawned on me then, that it had in fact been the pregnancy growing. The staff worked relentlessly to get me an appointment for a surgical abortion ASAP, however, waiting times were up to four weeks which would have put the pregnancy at 22 weeks; close to the upper limit. Every day that went by, I felt the control over my body slipping away, forced to carry a pregnancy I didn’t want, and had taken every step to ensure I wouldn’t have.

While I was very distressed at finding out I was still pregnant, a key factor in my distress was the concern and confusion of my family. My mother had been amazing caring for me while I had been debilitated by morning sickness – I had told them I had a stomach bug from travelling earlier in the year. This was wearing thin though, and they were asking more and more questions. I was exceptionally intimidated at the idea of having the surgical procedure done, as I had never been under general anaesthetic before. I felt the most vulnerable I had ever been. It felt like my body was conspiring against me and I just wanted my Mum. While there were pros and cons for telling her, ultimately, I decided against it. Trying to make this decision tore me up even more than the waiting for the surgery. Even though my mother knows about and supports my relationship; despite her nurturing nature, I knew her knowing would add to the guilt and internalised shame I had been conditioned to feel growing up. The fear of adding to my plate further was not an option when I already felt so traumatised. Everyday, I am deeply humbled by the connection and support I receive from my loving family – but I wish that that love and support extended to remove the taboo around sex and abortion.

When I finally went in to have treatment, I was just over 20 weeks pregnant. I had fortunately found a clinic with a very rare cancellation, albeit three hours from home. In the waiting room, I met a 31-year old British Pakistani woman, and we both laughed as we shared our circumstances, which were very similar. There was an immediate comfort in being able to talk to someone who understood my experience, without needing to share it in full. She was having her brother pick her up, having told him she was at a training event for work. She was concerned he might suspect something if he passed the building, so I walked her down the road to help keep up the facade, pretending to be a colleague from another office. After the treatment was done, I felt restored. Immediately able to eat; lighter both physically and emotionally. I felt free – back to me.

“In the waiting room, I met a 31-year old British Pakistani woman, and we both laughed as we shared our circumstances, which were very similar. There was an immediate comfort in being able to talk to someone who understood my experience, without needing to share it in full.”

Let me be clear – the fact medicine failed three times is exceptionally unusual. My IUD failing; the abortion pill not working; and the two subsequent pregnancy tests showing a false negative result – these are all incredibly rare in isolation, but for all three to happen to one person in one incident is a freak occurrence. I will be eternally grateful that the services I needed existed, for free, with ease of access. The care I received was excellent, and not a single medic shamed me throughout my experience (bar one GP, who condescendingly reminded me I was soon turning 30, and that the window to become a breeder is swiftly closing *eyeroll*).

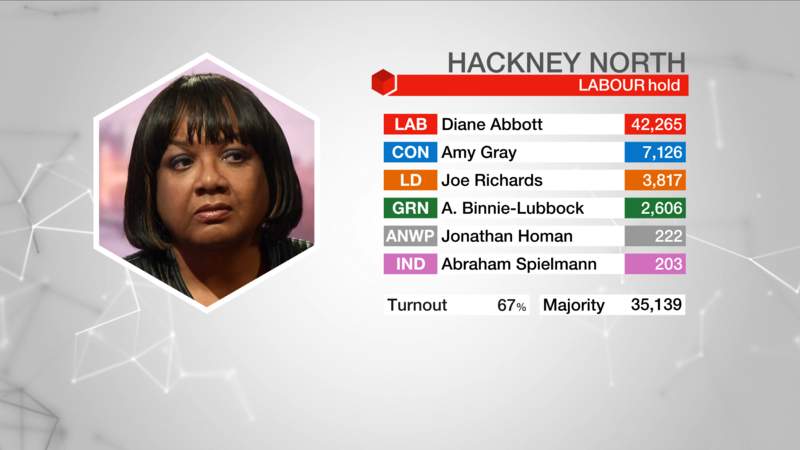

Abortion services are a vital lifeline for women, and especially for the vulnerable and marginalised. The idea that we may be facing a government formed with a fiercely anti-abortion party is diabolical. We cannot allow Women’s Rights to be gambled away as cheap leverage for political gain. Even the suggestion to reduce time limits for abortion is a possibility that frightens and infuriates me in equal measure.If they were to be reduced by even a few weeks, I would be a parent now, against my wishes and contrary to the steps I took to prevent it from happening. Let’s be real – the Tories and Theresa May have already shown us that they hate women, and especially women of colour. This is evident in a variety of their decisions: from allowing Phillip Davies to continue as an MP, to their refusal to release information about the sexual assault of migrant women.Throwing the DUP into that mix will only burn us faster and harder.

As my case illustrates, we desperately need to maintain and extend abortion services. We need more funding for targeted services for WoC, which the Tories are clearly unwilling to provide – they appear more likely to take away the little provisions that we have. While we fight for these services, we still need to keep women, and especially vulnerable WoC safe and supported when they want to make the decision to terminate a pregnancy.

It is imperative that we have the conversations needed to destigmatize sex and abortion in our communities. The less we talk about it within our communities, the more we risk isolating young women of colour further; and potentially putting them at further risk both emotionally and physically. At nearly 30 (with a very strong network of friends) I was able to navigate this experience, but I worry that younger WoC wanting to make this choice may not have access to a support network that allows them to feel safe and supported in their choice – let alone in their homes, where they should arguably feel safest and most held