Sugar. The silent assailant hidden in most cereals, sauces and breads. The new health criminal, which has recently been condoned as public enemy number one. Yet as I discovered after catching up with Social Historian Emma Dabiri about her new series The Sweet Makers: A Tudor Treat, I discovered just how rooted sugar is in the crown of the British Empire and our nation’s incredible wealth.

The three part series which airs on BBC 2 this Wednesday, takes four modern confectioners back through the history of Britain’s sugar obsession. The show challenges the sweet makers to recreate staple treats from various points in time that help visually mark out sugar’s transition from Tudor status symbol, to the middle classes of the Georgians, and then the mass production of the 20th century. This episode is guided by the food historian Dr. Annie Gray who sees the confectioners labouring over everything from toasted coriander seeds, to edible roses that were believed to cure gonorrhoea, to gorgeous syrup laden oranges. As one of the confectioners remarks, everything for the Tudors was about enchaining the flavours of sugar. The true depth of the show comes from how it then places these fun experiments next to the grim revelations of the slave labour that would transform the world of the British confectioner. One of the most resonant of the show’s revelations being how the slave trade created a surge in Britain’s sugar imports, with prices falling by 70 percent between 1640 and 1680. The only cost was that of the black body’s exploitation as free labour feed the supply of country. By illustrating the visual decadence of sugar with such exposes of sugar’s bitter truths the show, as Emma tells me, “centralises the conditions of the production of sugar as integral to the emergence of Britain as one of the world’s wealthiest nations”.

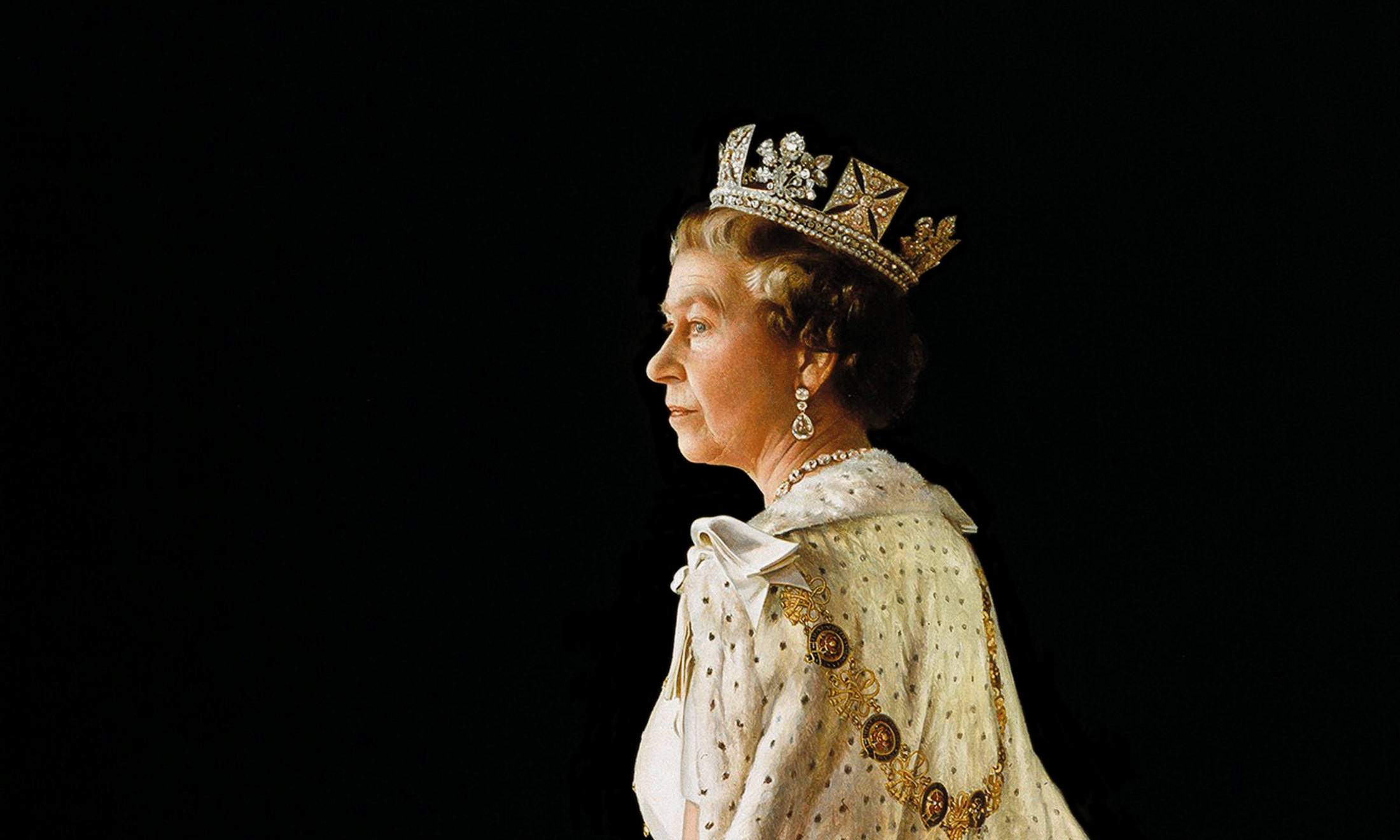

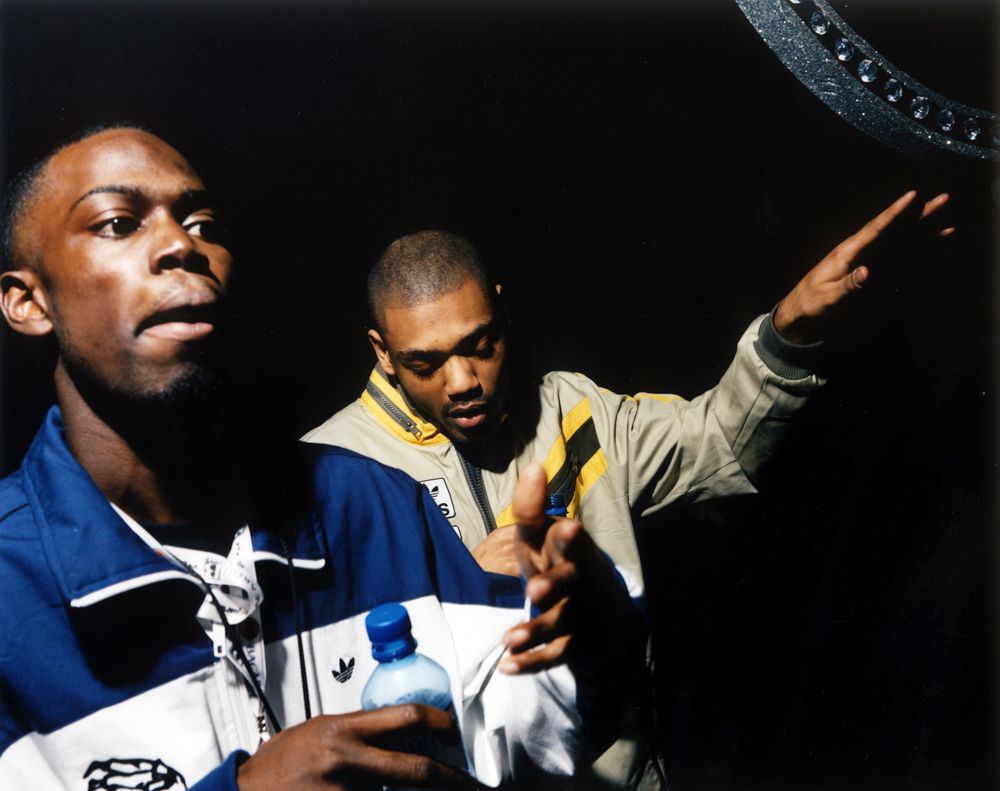

The Sweetmakers, image courtesy of BBC / Wall to Wall South / Sam Jackson

The Sweetmakers, image courtesy of BBC / Wall to Wall South / Sam Jackson

There are countless archives, books, and scholarship that document this fundamental part of British history, yet it is “not what the education system generally chooses to focus on”. Historical terminology attributed to Colonialism and Imperialism gloss over the horrors that they entailed: the “creation of an (ongoing) infrastructure to legitimise theft”. There is this disconnection between slaves as human beings that were (are), taken against their will from their country, shipped to a plantation, and forced into unpaid labour. This distancing between a word and a human face can be likened to how we refer to our own modern forms of slavery: Plantations and Slaves having their contemporary equivalent with Sweat shops and Immigrant workers. Calling these people workers instead of slaves, softens the reality that many of them have been forced into labour, extreme working conditions, and payed poverty wages.

Despite slavery being so entwined with modern European history it has been lumped into Black History month, as “some generous add-on that we should feel grateful is being included”. When the reality is that the exploitation of black people has provided the foundation for modern Europe’s story to develop upon for 500 years. The relegation of black history to just a month is counterproductive, and which Emma agrees “reinforces this idea that it’s something extra, something additional to normal British history”. This issue brings to mind a quote from a Zora Neale Hurston’s essay written in 1928, “I feel most coloured when I am thrown against a sharp white background”. Campaigns such as Why is My Curriculum White have continued to publicise this fundamental lack of diversity in the history classes of Britain. A highly problematic issue that stretches across the education system, and reaches up into the top of Britain’s elite universities. Oxford university have only this year decided that its History department will have a single and compulsory non-British, and non-European history exam. Although this is a rather feeble step in attempting to decolonise historical education. As when it comes to black history, Emma explains there is still no real initiative to learn about “pre-colonial African philosophy, technology and spirituality”. A critical issue that has provided Emma with one of the major driving forces behind her next book A History of Hair, which will be published by Penguin in 2018.

The deeper issue is how we have particularly with Africa been “conditioned to view it in a certain way”. As the show reveals the majority of black people forced into slavery on Britain’s plantations were taken from west Africa, and in particular Nigeria. Yet this continent has been constructed as a place where “bad shit just happens”, a distant land mass that has “child soldiers, corruption, genocide, famine, AIDS”. Either that or a fantasyland where writers such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899), can freely transcend whiteness at the expense of some misinformed Africanism. As Chinua Achebe has critically remarked this widely regarded classic of modernist literature, exemplifies how Africa has been crafted in the literary imagination as the “antithesis of Europe and therefore a civilisation, where man’s vaunted intelligence and refinement are marked by triumphant bestiality”. A Tudor Treat unravels these official narratives that “ignore the histories of the former colonies – and the role that Europe continues to play in the production” of Africa’s destruction. The show’s exploration of the slave trade, is testimony to how the structural problems that continue to ravage African countries are not the “natural order of things”, and because of the “barbarity and ineptitude of its people”. Instead the turmoil experienced by African countries is as Emma remarks a “direct result of a global world order” formatted by the Tudor’s to shape the Golden Empire, and ignite the slave trade. A colonial blueprint which was designed with the intention of keeping, and has kept, “African nations subordinate!”.

In fact many of the issues that continue to gravitate around democracies such as racism, sexual and gender inequality are not as we are led to believe as being the way of the world. In pre-colonial Africa these problems towards identity generally didn’t “exist as we understand it today, and operated very differently”. These rigid binaries are in fact rooted in a Eurocentric mindset. Whereas in pre-colonial Africa, “people’s affiliations or relations, be they ethnic or sexual or whatever, tended to be far more fluid and multidimensional and overlapping”. The narrative of Africa being made up of savage tribes is again largely a construction of the colonial imagination. The reality, Emma explains, is that although there were large groups of people, “their boundaries were far more porous and shifting”.These rigid identities that we hold to be “foundational and sacrosanct today”, and their innumerable problems, are the cause of conflicts, wars and genocides. These crisis are because of how we have become entrapped in “an eternal them and us logic”, which is yet “another legacy of colonialism”.

There is only one history professor of African Heritage in the UK, Hakim Adi, so where, as Emma rightly questions, are the: “Researchers versed in indigenous epistemologies? Researchers fluent in an African language? Is there a respect and understanding of the spiritual beliefs of the people they are studying?”. The root of the issue perhaps being in how a lot of “European scholarship is blinded by the arrogance of a mistaken belief in its superiority, so historians, or whoever, overlook valuable resources because they can’t recognise them for what they are”. The fruits of the British empire, which it is widely recognised at one point covered two thirds of the world, was only gained through the exploitation of the African people. Thus the good, the bad, and the ugly sides of British history are intrinsically linked and must be accounted for. To tell the good is simply a “work of fiction, but hegemonic history generally is a work of fiction, created to facilitate ideological objectives”. The show brings to light some lesser known truths about individual slave plantations, such as the ghastly tactics used by owners to curb the surge in their slaves committing suicide upon arriving on the plantations. A revelation that brings one of the sweet makers, the Nigerian born Cynthia, to a teary remark of how it was financial greed and not the sugar itself that fuelled the cruel trade. Through weaving the decadent treats created on the show with shocking revelations surrounding the slavery that manufactured this commodity, Tudor Treat exposes just how decayed our ideal of British history is, and how it has misconstrued our sense of historical reality.

The infrastructure of the Empire is still incredibly present in the economic framework of global affairs: in its systematic theft of resources from colonies that Europeans profit from. The only difference perhaps being “international trade, international (under) development” has become rigorous in its efficiency; continues to “operate according to the same logic, that they got on lock back in the day”. Even the promotion of fair trade goods like sugar, are being reversed by supermarkets such as Tesco and Sainsbury’s. Both of whom have expressed a recent desire to readjust the agenda for their own self defined “fairer trade”. There is a link between the people who participated in slavery and its normalisation 500 years ago, with our consumer attitudes today. As sickening as it sounds they too “were normal people going along with what was acceptable at the time”, and it generally made their lives more comfortable. The same can be said of our own habits towards consumption and the ways in which western companies use exploitation to maximise profits. You only have to look at the accessibility of “cheap and disposable fashion”, or food fads such as coconut oil that create huge corporate gains at the huge losses of impoverished farmers. Even mobile phones which “are today a central tool of activist organising contain coltan, the mining of which has been devastating to the Congo: capitalism makes us all complicit in exploitation”.

Tudor treats exposes viewers to the real cost that “black people of African descent, paid to make modern European nations the countries that they are today”. Slavery has been an integral part of the success of the British economy, and as we continue to debate if slave traders names should be removed from road signs and concert halls, there needs to be broader conversations on the slavery that continues to persist today. The series acts as good starting point in stretching beyond historical facts and urging the viewers to “question the very logic of capitalism”. The byproducts of capitalism it appears are still those who are non-white, and structurally black people have especially not reaped any meaningful benefit under capitalism. Tudor Treats pinpoints an era that saw the fruition of today’s capitalism and European wealth, through the forced labour of African people some 500 years ago. By weaving the tantalising attempts by the confectioners to recreate their sweet Tudor delicacies with the revelations of the human cost behind it, the show provides crucial links in rethinking about products and production. It is through this that the viewer can, as Emma hopes, discover how “the timeframe of the rise of capitalism correlates with the most oppressive periods for black people”. Something we all need to switch onto and think about.