“Boys do cry, but I don’t think I shed a tear for a good chunk of my teenage years”

Last year, following on from the release of his eagerly awaited comeback album, Frank Ocean mused online about the message behind Blonde. His then forthcoming project was set to see fans and critics alike unite as both Endless and Blonde made their debut to the world. Frank’s, well rather frank, discussion prior heard him speak heavy-heartedly about the emotional release he experienced during its creative conception.

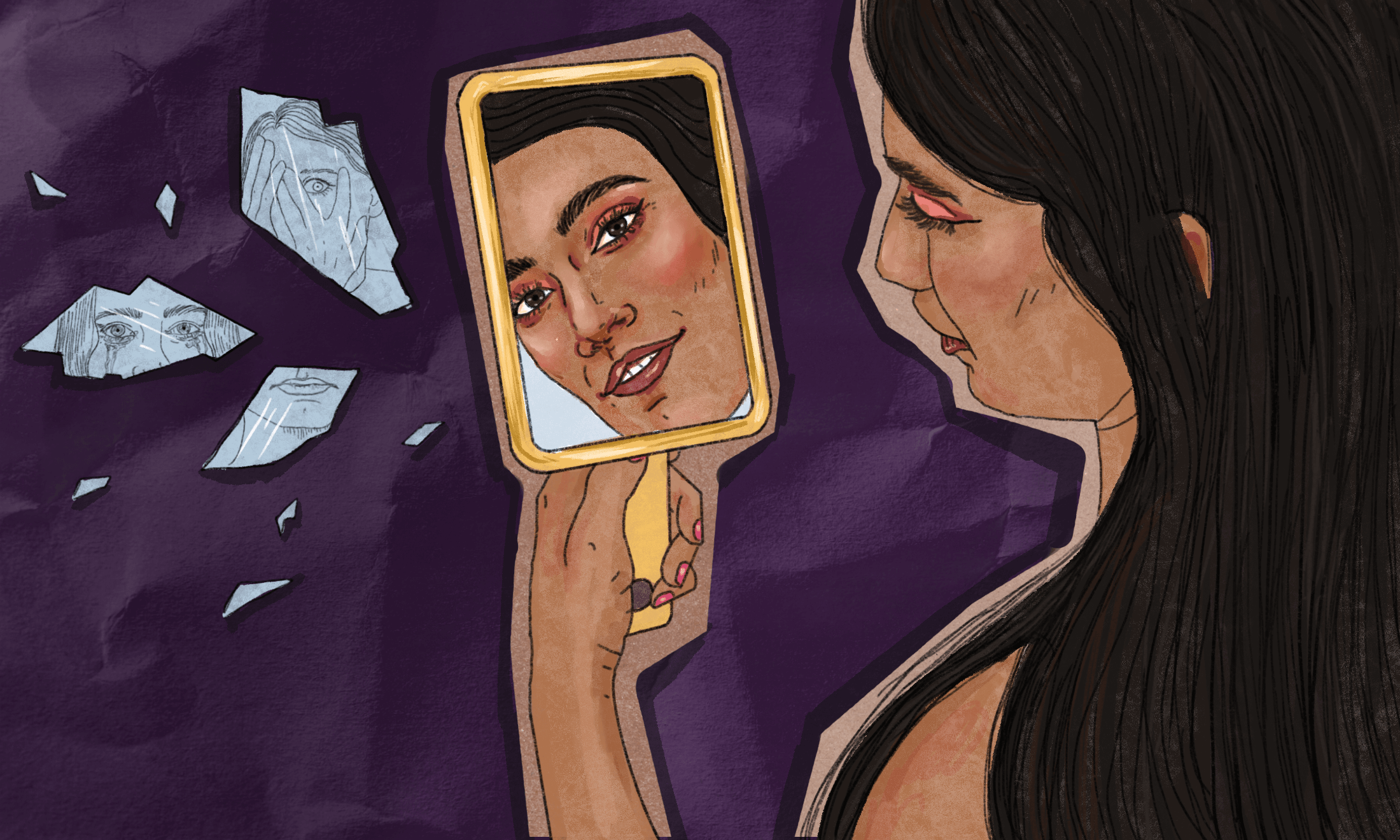

But from Frank to Future, James Blake to Drake, commercial success is often found in an artist’s purest and most raw productions. It’s no secret that emotional vulnerability has been documented in musical landscapes for far longer than the trends of today. But as it seeps its way into the charts and into the discourse of what is now considered pop, is it a case of the industry capitalising on a pop-star’s pain or do we, the people, just really love a good sad song?

Let’s look at Drake. A loveable rogue who also sends a slight nervous shiver down your spine at the thought of being left alone. You’ve met many a Drake on a night out. He can often be found on the edge of the dance floor, or hanging by the side of the bar. The self-proclaimed “nice guy” imploring you to smile despite you, a human of free-will, being incredibly content with your resting glare. More meme than man these days, he has built his empire on his woes. Like, literally.

“Drake’s discography is a never-ending exploration into unrequited love, rejection and sensitivity”

His discography is a never-ending exploration into unrequited love, rejection and sensitivity. With his recent release More Life moving away from the likes of ‘Marvin’s Room’, he still couples his boyish, bashful bravado with, what appears to be, sincere professions of distrust and regrets along the way. His collaborations with the melancholic mumble rap figure that is Future were a natural progression in his earnest explorations into heartbreak.

Future, for all his flaws, is also a tortured artist by nature. His track, ‘Codeine Crazy’ has over 20 million views and is considered to be one of his saddest, and perhaps greatest tracks to date. He cries out, “I’m an addict and I can’t even hide it”, his yearning to escape resembling a confession as the song flows like a hazy stream-of-consciousness. He’s manic but the façade has long faded. He is, essentially, emotionally exposed, and as a young, black man his mental health should be considered more than just a hook.

The vulnerability of young, black mental health is a frequent debate, as seen recently in the unethical NME cover story of Stormzy. Despite the narrative being incredibly serious and – if covered correctly – rewarding, treating mental illness as a USP is a mistake and completely glosses over the issues at hand. Mental health has a certain commercial power and when combined with how the media already portrays and stigmatises the young black man, it strips the subject from their story and markets it as something profitable.

“Musical idols are very much role model figures, and therefore, they have a platform to help those without a voice.”

Between 2011 and 2015, mental health trust budgets in England were cut by 8.25%. So when figures from the Samaritans showed that over three times as many men committed suicide in 2014 than women, it is obvious that as a society we need to address the subject in whatever capacity we can, be it through music or otherwise. Whilst it isn’t the core solution, for many young people their musical idols are very much role model figures, and therefore, they have a platform to help those without a voice. Stormzy’s doing it. Kendrick’s doing it. Damn. Just look at the heartbreaking heyday of the ‘old Kanye’.

808s & Heartbreaks, West’s 2008 LP saw his auto-tuned landscape of loss, grief and utter fragility looping over frosty instrumentals in what is now one of his most influential and sincere releases to date. Overtly introverted, much like his contemporaries today, you don’t have to be a fan to hear his emotional pleads between the beats and the boasts.

The album’s closing track, ‘Pinocchio Story’ is utterly devastating. Blaming himself for his mother’s death, he places fault in his life choices and implores eternal unhappiness due to his failures. An article for the LA Times made the apt comparison, “Like the album’s titular Roland TR-808 drum machine — a gadget once derided for its seeming inhumanity and later a staple of all pop music — inhumanity can make an artist go deeper.”

What do we, the people, get from our idols and our inspirations baring their souls like this through their work? From going deeper?

What do we, the people, get from our idols and our inspirations baring their souls like this through their work? From going deeper? Well, much like any art form, music exists as a form of self-expression, before the profitability and the cut-throat capitalism of the industry. Whilst any bright, young thing can be modelled and moulded into the next phase of pop-stardom, without the substance behind the songs, the relatability just isn’t there.

It’s why we covet emotional musical content. Tales of lost love, fears, hopes and dreams plague us all as we go about our lives. It makes artists relatable, and thus, their commercial stock goes up. The brooding boy will continue to play a role within the musical climate of today and tomorrow. For every young MC, producer or vocalist divulging their demons with the world, there will more media misconceptions and more marketing mishaps. So, before we get too caught up in the high-lives of our problematic faves, we should know how to discuss the lows too, within the media and within our own social circles. Let’s be frank.