Teenage girls honestly get the most crap for expressing how they feel. Particularly black teenage girls. I developed BDD in my early teens and certainly wasn’t given any allowances for being mentally ill.

According to the NHS, body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) also known as body dysmorphia, is an anxiety disorder that causes a person to have a distorted view of how they look and to spend a lot of time worrying about their appearance. I don’t know why I developed BDD (I’m still trying to figure it out, holla at me if you got any pointers,) but as a black female I was not allowed certain privileges. I developed the mental health condition at the age of fourteen while still in school, and instead of being offered help and support from my teachers, I was assumed to be a drug addict (crack cocaine, the most racialised drug out there – what else?) and threatened with exclusion on no evidential grounds. At the same time another student with a mental health condition was granted permission to be homeschooled, but could come back to classes whenever they liked. So while I was questioned over the reliability of my mental health condition; another was treated with care and complete understanding. Weird.

However, my (amazing) mother fought for my rights when I couldn’t, and after much deliberation I was referenced to CAMHS, the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, through which I was put in touch with the Maudsley Hospital – the largest mental health institution in London – to begin treatment.

“My story is a lucky one, but I could have been seen a lot sooner. It also doesn’t cover up the fact that black women and girls are criminalised when it comes to mental health.”

My story is a lucky one, but I could have been seen a lot sooner. It also doesn’t cover up the fact that black women and girls are criminalised when it comes to mental health. We aren’t allowed the time or space to recover. The idea that we are sick and need help is seemingly mythical and rather we are perceived to be “acting up” or “hyperemotional”. We aren’t allowed to express our emotions, even when they are rational. Despite now being healthy, I’ve lost count of the times I’ve been told I’m overreacting when expressing how I feel. Or, even better, just being an “Angry Black Woman”. The picture is even worse for young black men.

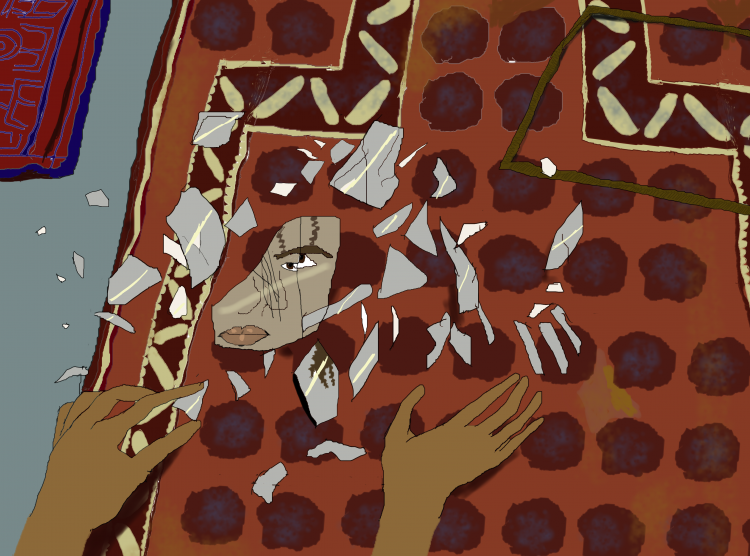

Specifically to BDD, and even for non-BDD sufferers, regardless of how “attractive” we are, our image forms a crucial part of our identity. If you are told throughout your life that your appearance, relating directly to your race, is not the “default” or “standard”, you begin to question your own humanity and self worth. This is why adopting exclusively European beauty ideals (and general societal norms) is not only supremacist and echoing of a eugenic narrative, but also toxic to those identifying as BAME. When our confidence is worn down, it has a hugely detrimental effect on our productivity, relationships and our general well being. When my illness was at its worst, I was right in the middle of my A-Levels; I planned to go to UCL to study Psychology, but instead stayed at home for six months and missed most of my exams. I only left the house after buying a straightened wig, or wearing a headscarf, removing an indicator of my colour – my afro hair – and assimilating to white standard.

One type of “beauty” is not naturally better than the other, just different. Being proud of my blackness by having my hair natural and enjoying my black body for what it is is seen as some sort of radical self-acceptance movement. And in some ways, it is. It’s a hell of a lot easier for me to get up in the morning and style my hair in a fro than it is to straighten and “tame” it, but it’s also an act of self love after all the years I spent hating it.

“Beauty is not a spectrum, not a measurable quality as pseudo-science will have you believe.”

Beauty is not a spectrum, not a measurable quality as pseudo-science will have you believe. For example this terrible article I came across the other day ranking “10 of the world’s most beautiful women” is not only an incredibly sexist article (and an awful example of clickbait) but is unsurprisingly washed with the typical indicators of “Western” beauty – light skin, straight hair and European facial features. Black hair products are marketed on their ability to “straighten” and “slick” our hair; we are constantly told to contour our noses so that they are smaller and less broad, and skin bleaching products are as popular as normal moisturisers in parts of the UK with high BAME populations. For us to simply be ourselves is nothing short of incredible and a testament to our strength.

Despite the incredibly hardworking NHS staff that helped me on my journey to recovery, I was diagnosed firstly with depression, then anorexia, then anxiety, before finding the root of the problem: BDD. This suggests that BDD is not only a difficult condition to diagnose, but it also needs to be talked about more amongst psychiatric professionals. In an era where we are seeing more and more young people being diagnosed and admitted to hospital due to their mental health, especially amongst POC whose appearances are underrepresented in all forms of media, this needs to be changed.